Advertisement

Lisa Gershenson on the indelible lessons learned from Dashi and Umami

10 July 2019 · Behind the Cookbook

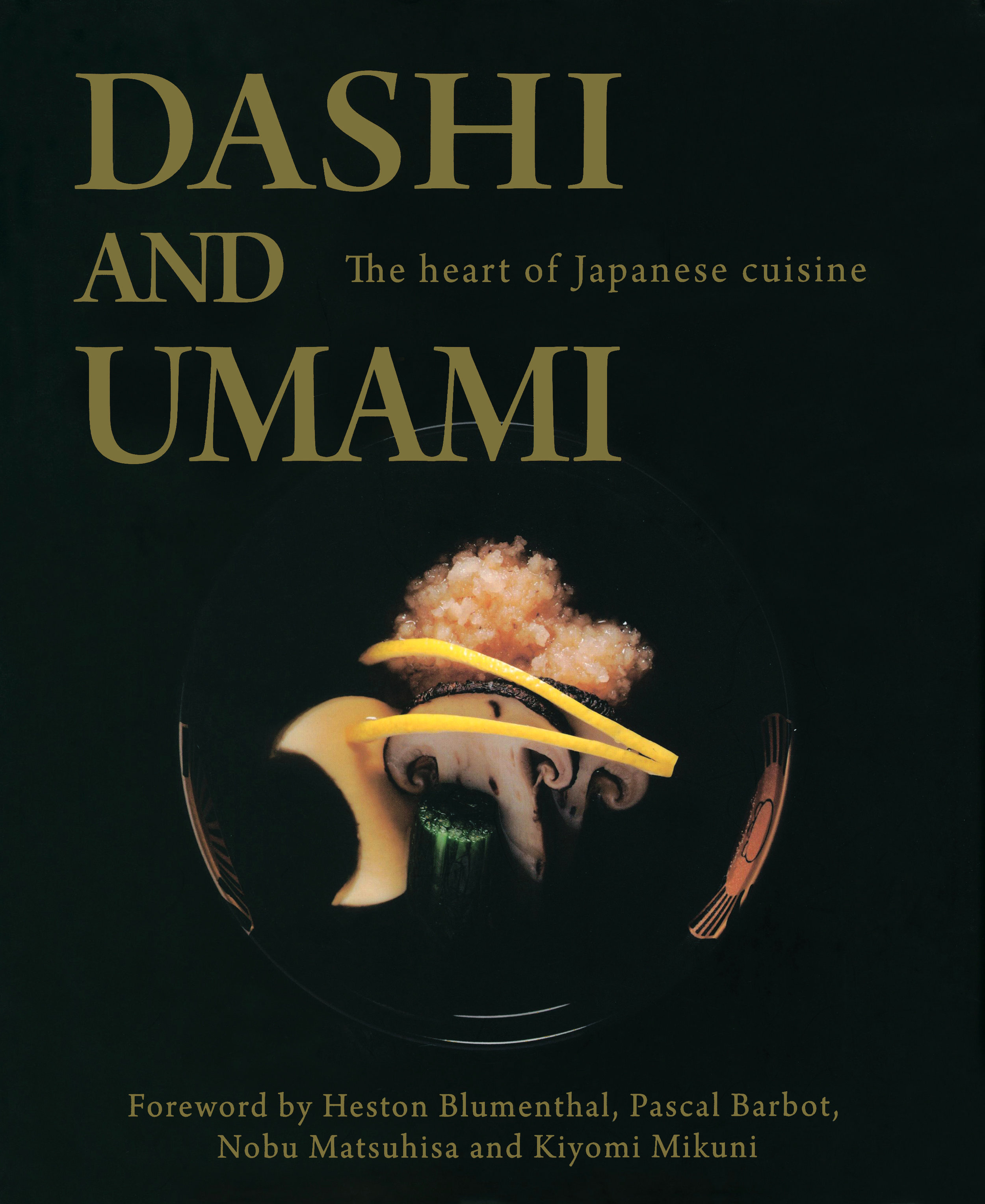

“Dashi and Umami has left an indelible mark on my culinary style”

by Lisa Gershenson

Since my first trip to Japan in 1978, I have been drawn back again and again; and food is always the organizing principle of my visits. On some nights, I enjoyed the elegant choreography of courses at formal kaiseki restaurants. On others, I lingered in smoky drinking spots, sampling their offerings of skewered meat and vegetables. I have been seated at counters watching tempura chefs fry baskets of seasonal ingredients to crisp perfection, experienced the rituals of traditional sukiyaki diners, slurped noodles at ramen shops, and had the opportunity to experience shojin ryori, Japan’s sophisticated Buddhist cuisine. Despite having experienced all these facets of Japanese cuisine, my own attempts to replicate what I had enjoyed always seemed to fall short. This changed after I read Dashi and Umami: the Heart of Japanese Cuisine, published by Eat-Japan/Cross Media Ltd .

Dashi and Umami introduces readers to the distinct philosophy underlying traditional Japanese food. Influenced by Buddhism, Japanese culinary philosophy is rooted in a deep respect for the characteristic taste of each individual ingredient, and the specific season when that ingredient is at its peak quality.

The book describes the Japanese idea of 12 seasons—spring, summer, fall and winter, each again divided into early, middle, and late periods—and the important differences between them. Dashi and Umami explains the Japanese notion of shun, used to describe ingredients when they are at their peak flavor and texture, perhaps most familiar to other cuisines’ concepts of seasonality. But, through Dashi and Umami, I also came to appreciate other phases of an ingredient’s integrity. The book taught me to appreciate the concept of shiri, used in Japanese culinary philosophy to describe produce from the very first harvest in a season. Though these ingredients are not yet at their peak, shiri foods are a good choice for the diner who can barely wait for the old season to retreat. There are also options for those who still crave flavors beyond the point of an ingredient’s harvest perfection. These foods are categorized as nagori. Equipped with these philosophies, Dashi and Umami taught me that the cook could stir up eager anticipation or melancholic nostalgia just by the choice of ingredients.

The connection between food and nature is also honored by the selection of cooking method and table setting. Think of the satisfaction brought by a braised dish on a cold winter’s night served in a steaming iron pot, or on a hot summer’s day, the pleasure of chilled noodles garnished with raw fish and green onions atop a cold, glass plate. Along with these terms and philosophies, Dashi and Umami provides menus and recipes from formal kaiseki restaurants to help the reader celebrate each of the seasons as Japanese cuisine does.

Dashi and Umami also deepened my understanding of umami . Though, today, the term is incessantly tossed around, the book digs deeper, describing umami as the backbone of Japanese food, tracing the concept back to a scientist’s discovery at Tokyo Imperial University in 1908.

It is in dashi, the stock that forms the basis for almost all Japanese culinary preparations, that umami’s essence lives. Eiichi Takahashi, a 14th-generation owner of a 400-year-old Japanese kaiseki restaurant, writes that “dashi is so indispensable that it becomes a part of our bodies...the fragrance of the ocean provides the tongue with a deep, subtle experience of umami and the refreshing aftertaste calms the heart.” The book addresses in depth the ingredients and precise method to make dashi, and its myriad uses.

Dashi and Umami has helped me understand how the Japanese think about food. The book illustrates the way in which chefs pay respect to nature while celebrating the pleasures of taste. By helping me to appreciate these philosophies, Dashi and Umami has left an indelible mark on my culinary style. Now, when I try to recreate my favorite Japanese experiences, they have a context and feel complete.

Lisa Gershenson is the publisher of the on-line magazine Cook’s Gazette, Lisa@Cooksgazette.com.

Explore Lisa’s list of her most essential cookbooks on 1000cookbooks.com.

Dashi and Umami is a featured title on ckbk, home to the world's best cookbooks and recipes for all cooks and every appetite. Start exploring now ▸

Sign up for ckbk's weekly email newsletter

As an added bonus you will receive a free PDF download featuring recipe highlights from our favorite cookbooksAdvertisement