Advertisement

Foams: Thickening with Bubbles

By Harold McGee

Published 2004

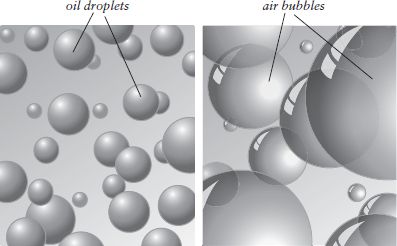

Thickening a liquid with oil droplets and air bubbles. These tiny spheres act much as solid food particles do, interfering with the flow of the liquid surrounding them.

At first it seems surprising that a fluid can be thickened by adding air to it. Air is the opposite of substantial! Yet think of the foams on an espresso coffee or a glass of beer: they all have enough body to hold their shape when scooped with a spoon. Similarly, a pancake batter gets noticeably thicker if you stir the chemical leavening in last. In a fluid, air bubbles have much the same effect as solid particles: they interrupt the mass of water molecules and obstruct the water’s flow from one place to another. The disadvantage of foams is that they are fragile and evanescent. The force of gravity unceasingly drains fluid from the bubble walls, and when the walls get just a few molecules thick, they break, the bubbles pop, and the foam collapses. This outcome can be delayed in a couple of ways. The cook can thicken the fluid with truly substantial particles or molecules (oil droplets, egg proteins) to slow its drainage from the bubble cell walls, or include emulsifiers (egg-yolk lecithin) that stabilize the bubble structure itself. On the other hand, the very delicacy and evanescence of unreinforced foams is a part of their appeal. Such foams must be prepared at the last minute and savored as they disappear.