Advertisement

Kitchen Porters

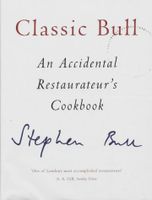

By Stephen Bull

Published 2001

There’s a riveting account in George Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London of pre-war life in the service areas of the Hôtel Crillon, particularly of the plongeurs who led a troglodytic life of unremitting toil in the hotel’s hot and fetid bowels. The lowest in the highly structured pecking order of the staff, the plongeurs were the most despised and exploited, with no one beneath them to assuage their feelings of insignificance. Their mechanism to combat this and generate some self-respect was to convince themselves they were the only ones who could endure their horrendous workload and inhuman conditions, and thus protect themselves from the knowledge that they weren’t at the toe of the world’s boot. They could then even look down on the lowest cooks and waiters as namby-pambies who would faint at the sight of an encrusted, burnt-on, fifty-kilo copper stockpot. ‘Je suis dur. Je suis dur,’ was their incantation. If you repeat it for long enough, does it work? I’ve tried doing it but I haven’t the stamina. Although they are rather better treated now, the modern version of plongeur, feeble in its euphemism ‘kitchen porter’, can sometimes be more an unsung hero than a downtrodden victim. His old skills of cleaning tinned copper with salt and lemon juice have been replaced by the simple elbow grease needed for stainless steel; the pre-wash spray, the pass- through dishwasher and detergents in pumps have reduced even this physical labour. Quite right, too, because in theory it has freed the KP to do other things. A good one will not only keep the kitchen clean, but will prepare vegetables, wash and pick salads and herbs, descale fish, and generally improve the lives of the cooks. In short, to quote an Australian chef of mine, a good one’s worth his weight in wallaby droppings.