Advertisement

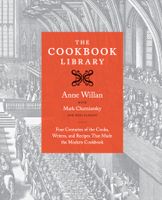

The Italian Trendsetters

By Anne Willan

Published 2012

The new century dawned with the publication of two enormously influential cookbooks, one in Italian, the other in French. Neither was an original work, instead echoing the very first printed cookbook, Platina’s De honesta voluptate et valetudine (Of Honest Indulgence and Good Health, 1474). Platine en françois, published in 1505, was not a direct translation but a sophisticated adaptation of the original Latin work that added a good deal of new culinary and medical material. Epulario, published in 1516, was reputedly by a certain Giovanne Rosselli, but the recipes repeat almost word for word those in De honesta voluptate. Venetian publishers seem to have been the moving force behind this book, which proved to be a best seller, and Rosselli’s name was dropped in later editions. Epulario continued in print for nearly two centuries. Both books illustrate the “family tree” principle that had begun in the 1400s, in which each new cookbook drew on its predecessors. In other examples, Taillevent’s Le viandier (The Victualler, 1490) and the anonymous Le ménagier de Paris (The Householder of Paris, a manuscript from 1393) were echoed in several modest pre-1550 French cookbooks that were also copied from one to another. According to historians Mary and Philip Hyman, “The public could choose between at least five créations with some or many recipes in common.”1