Advertisement

Main Courses

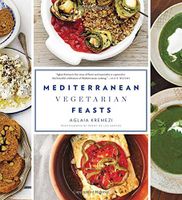

Published 2014

Frugal cooks around the Mediterranean were limited to a small variety of vegetables and greens for months on end, so they devised an incredible number of ways to prepare them differently. They stew vegetables with aromatics, stuff them with bulgur or rice, grate them, and mix them with cheese to make the filling for pies, or fry them and serve them with tarator or skordalia.

The most beloved of all summer dishes are the vegetable stews called ladera in Greek, zeytinyagli in Turkish. Green beans, okra, eggplants, and zucchini are cooked in an onion-tomato sauce, often accompanied by potatoes, bulgur, or homemade pasta. Or they may be served on their own, with a side of feta or local cheese and plenty of crusty bread to soak up the wonderful juices. These dishes may also appear as side dishes to meat or fish. Peas, artichokes, fresh favas, zucchini, and carrots taste particularly delicious when cooked in olive oil that is brightened with fresh lemon and scented with fennel or dill.

Stuffed vegetables and grape or other leaves, rolled around a stuffing, are another important group of traditional vegetarian dishes. Vegetables suitable for stuffing include tomatoes, peppers, zucchini, squash, eggplants, and onions; quince, a much-loved winter fruit used in both savory and sweet dishes throughout the region, also lends itself to a spicy stuffing. Rice, bulgur, barley, and other grains are cooked with onion, garlic, and herbs and are often complemented with nuts, then stuffed into hollowed-out vegetables, which are either baked or cooked on the stovetop. In the winter, when freshly harvested garden vegetables are scarce, Mediterranean cooks turn to greens. The wild leafy plants, called horta in Greek, grow in the hills or as weeds among the crops. Braised and complemented with grains or potatoes, leafy greens are a winter staple. They are also the basic filling for traditional hortopita or spanakotyropita. Eastern Mediterranean pies (pites or börek) are the kind of convenient, seasonal food that only resourceful cooks with limited ingredients could invent. Besides being irresistibly delicious, pites—especially those made with foraged plants—contain antioxidants and other nutrients that promote good health, scientists have discovered.

Legumes of all kinds, often complemented by grains, have been Mediterranean staples since antiquity. Cooked by themselves or combined with seasonal vegetables, legumes form the base of family meals. Chickpeas, sealed in clay pots and left to cook overnight in the receding heat of the wood-burning oven, were a Sunday dish throughout the Greek islands. Falafel and the immense popularity of hummus (the word for “chickpeas” in Arabic) have given an international leading role to the once humble chickpea—my favorite legume. Dried favas were the ancient Mediterranean bean. When more refined white beans came from the New World, they often replaced dried favas, which take longer to cook. Fresh favas have been rediscovered recently by creative chefs, but in the Mediterranean they have always been used in some of the most popular spring dishes. In our garden we plant favas in October to enrich the soil for the tomatoes, eggplants, and peppers that we plant in April and hopefully enjoy all through the summer.

© 2014 All rights reserved. Published by Abrams Books.