Advertisement

The History of Baking in Mexico

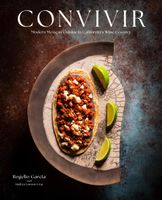

Appears in

Published 2024

Starting with the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors, baking gained a foothold in Mexico and eventually flourished. Wheat was needed by the Catholic Church for the Holy Communion wafer, and bread played an important cultural role as a marker of elite social status.

Baking in Mexico experienced a further boost a few centuries later during the French Intervention, the occupation of Mexico by Napoleon III in the 1860s. Although brief, the culinary contributions of that period are significant, resulting in what is called la comida afrancesado (a fusion of Mexican ingredients and French techniques), with baked goods arguably the most impactful development. For example, pan de muerto, an integral part of Día de los Muertos celebrations and altars, would not exist without the influence of the country’s Basque bakeries, as the basic ingredients—butter, cane sugar, and wheat flour—were not known in Mesoamerica prior to conquest.