Advertisement

Why ‘making do’ is not a burden

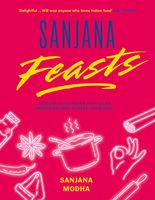

Published 2024

They say that the regional cuisines of India change every two miles, influenced by local culture, trade, migration and not forgetting the imperial rulers of the past. The Mughal Empire, from 1526-1857, followed by The British Raj from 1858-1947, when Hindustan became what we know today as the independent nations of India, Pakistan (and in 1971, Bangladesh, which was formerly known as East Pakistan). Local cuisine was also heavily influenced by trade, which began around 500 bc, maritime trade, and The Silk Route (around the fourteenth and eighteenth centuries). Today we live in a connected world, a melting pot more diverse than ever before. For generations, migration has meant that people have adapted and assimilated when it comes to unknown ingredients, using local produce to cook the foods they know and love in their adopted foreign lands. For British Indians, spicy, oniony masala baked beans on toast, or canned tomato soup with a ghee and curry leaf tempering are two prime examples. My Tanzania-born father is a fan of ‘fruit jelly salad’ made with Princes canned fruit, strawberry jelly (jello) and evaporated milk. His mother baked Bird’s custard powder cakes inside a sand oven in Mombasa, Kenya. For years in our home, we used mushy peas in place of yellow peas when making my mother’s recipe for raghda pattice (Gujarati potato cakes). This is something she picked up in the 1970s when the customary ingredients were not as readily available as they are today. Why am I telling you this? Well, when in conversation, much of this is perceived as diasporic communities ‘making do’. Whilst this may have been true for some, especially those earlier generations who had to replace India’s hero herb coriander (cilantro) with parsley, jaggery with brown sugar, and nuts with Weetabix (for multiple reasons from financial to seasonal), I believe it was much less of a compromise for generations like mine who were born into this fluid style of eating. We flit between food cultures because it’s what we know. In fact, assimilation food is more than simply ‘making do’. It is an opportunity to delve face-first into exciting foods that have a sense of the new whilst still feeling the comforting connection of familial roots. Assimilation food is as uniquely interesting as those who cook it. It also tells a story of heritage interlaced with movement and cultural change. With claims of authenticity comes bags of subjectivity. Does authenticity mean I only cook millet in the winter and sorghum in the summer, according to a centuries-old custom in India? Does cooking authentically mean we should always add asafoetida when cooking lentils and pulses like Ayurveda tells us? Should tadka or spice tempering happen at the beginning of the recipe, at the end, or both? Ask ten different people and you’ll probably get ten different answers because the nuances of Indian food are both hyper-regional and personal. If you think about it, what is now deemed to be authentic, wasn’t always. Historically, through trade routes came potatoes, tomatoes and chillies; all used abundantly in Indian cuisine today, and introduced by Europeans (the Portuguese, Dutch, British, and others), and with origins in the Americas and Caribbean. By no stretch does this render India’s modern favourite – the tomato-laden curry, butter chicken – inauthentic because innovation doesn’t cancel tradition, or vice versa. Today, tradition and innovation coexist quite happily, creating some of the most remarkable tasting dishes, many inspired by global cuisines.