Advertisement

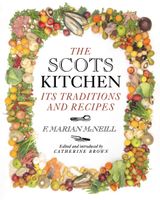

Oatmeal

Published 2015

Oatmeal, like coffee, must be closely packed and kept airtight. In many old farmhouses there still stands the solid oak chest, or girnal, which after every harvest is packed anew with sweet-smelling, nutty-flavoured oatmeal.1 In the small croft-houses, a seasoned oak-barrel serves the same purpose. Other woods can be used, provided they are odourless and tasteless, or nearly so. Resinous woods are, naturally, avoided. The receptacle has to stand in a dry place, as dampness ruins the flavour of the meal. Well packed, it may be kept for a year or longer and, indeed, is considered to improve in sweetness and digestibility as it matures. (New oatmeal is heating.) A good miller knows just what samples of grain to select, just how long the process of drying in the kiln requires, just how to set the stones for the correct shelling and grinding of the cleaned and dried oats. The method of kiln-drying is somewhat more arduous than the modern method of mechanical drying, but it is to the kiln that we owe the delectable flavour of the best oatmeal.1