Advertisement

Preparation info

- Serves

8

- Difficulty

Easy

Appears in

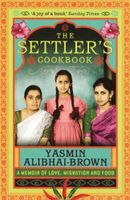

Published 2009

Ingredients

Method

- Heat the butter at a low temperature in a heavy-bottomed pan with a lid you can put in the oven. Throw in the pods.

- When they start to cook, add the carrots and stir, cooking slowly for five minutes, then add the fresh milk, cover (leave a slight opening) and cook over very gentle heat for ten minutes.

- Check and stir often.

- Add sugar and milk p