Advertisement

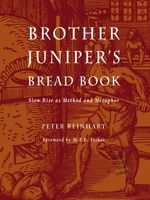

Too Many Rises, Or The Pitfalls of Slow Rise

Appears in

Published 1991

With the slow-rise method, we stress multiple long rises as a way to develop flavor and character. I have used this method for many types of bread but there are two caveats that need to be explained. The first is the possibility of too many rises; the second is that not all breads lend themselves to the method, Struan being the most notable example.

The best known bread in the world is classic French bread in its many variation. It is also the simplest in terms of ingredients but the most complex in terms of preparation. When you consider natural starters or sponges, levain-type slow-rise methods that take days, or hearth baking that requires high temperatures, the whole process can be rather intimidating. For this reason at Brother Juniper’s we focused on the simplest methods and principles that still produced the highest caliber, prizewinning breads. There are wonderful breads being made by all sorts of intricate methods, many of them impractical for the home baker, except for the fanatical hobbyist. (Note: Since writing this line in 1991, I realize that the fanatical home baker is no longer a small demographic—there are now many thousands who sincerely do want to know, and will use, the most complex of baking techniques to achieve world class bread.) There are breads that only work if the grain is milled that day, if the temperature is constant at 80° F., if the starter is used only after it has been buried for a week in ash or sand to age, if made with a sponge method, if baked only in a certain type of brick oven, and on and on. Bread is incredible, even miraculous. It is almost always delicious, especially when just out of the oven. It is forgiving but only to a point. Awareness of some of the pitfalls of slow-rise breadmaking should allow the home baker to avoid failure or disappointment.