Advertisement

Bali

Published 2004

Ritual flower heads.

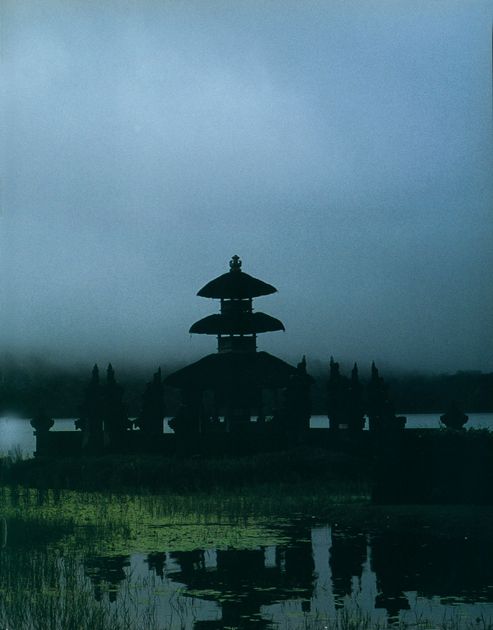

The crater lake at Bratan, Northern central Bali, a magical and serene mirror-glass of water, is home to the goddess of irrigation, Dewi Danau, and a thatched seventeenth-century lake-side pagoda Buddhist temple (Pura Ulun Danau).

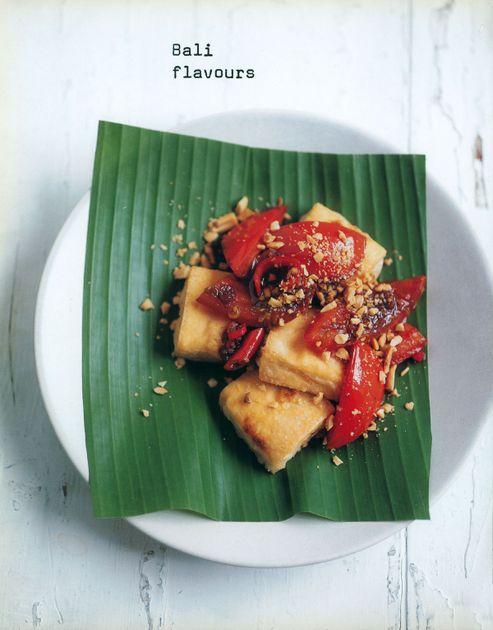

Tofu with chunky tomato sambal. Sambals are hot and spicy relishes, and come with everything.

Bali is but one small island in the vast archipelago that is Indonesia. Yet, in culinary terms at least, it is the brightest waterlily in the Indonesian pond - a varied and veritable cast of thousands that includes the Malaku islands (formerly Moluccas), famed for their spice. Islands that have gone through the mill of invasion, occupation and cultural assimilations - including tourism. Yet life remains humble, contentedly jogging along with its deep-rooted respect for all that sustains it: the land, the air and the sea. The spice islands’ plantations of clove, cinnamon and nutmeg, and the towering groves of kenari nut trees are no longer the trading commodity they used to be, yet they stand testimony to the Dutch occupation and still help sustain the population. Indonesia’s food is one of those global melting-pots that’s been left on the back-burner, on slow simmer, for centuries. Malay ancestry fused with Chinese, Indian, Dutch, Portuguese, Spanish, Arab traders, colonizers and local blood have all added their bit, and it’s time that we in the West lifted the lid on this exotic pot and got stuck in. Staples and flavourings that crop up throughout the islands are; rice, chillies, coconut milk, kecap manis (a thick, rich, sweet soy sauce, and incidentally where we nabbed the word ‘ketchup’ from), shrimp paste (terasi), candlenuts (kemiri) and palm sugar. These are blended and balanced with other things. For every sour or salty flavour there’s a counterbalance of sweetness; dishes blistering with chillies come with cool sliced fruits or something steeped in coconut milk. Flavourings come fresh, as opposed to powdered; leaves, roots, stems and fruits are chopped, smashed and pounded into pastes as and when they’re needed. Sambals (coarsely chopped hot sauces) are served with many things and they’re wokked with petai beans and eaten with curries - as are acar (pickles). Think Bali. Think green. Think acres of paddy fields. Contoured arrangements of dazzling cellulose-green steps colonize Bali’s every available hillside. No prizes then for guessing that rice (in white, red and black) is the key staple. Paddies also support fish and float with happy Bali ducks (their droppings further nourishing the rice, frogs and eels) that end up hung, drawn and quartered at the markets. Plain boiled rice is the every-dayer, yet they get inventive with it too, flavouring it with coconut milk and pandanus leaf or lemongrass, or with shrimp paste and sambal, and then wokking it to make their golden oldie, nasi goreng. Rice is ritual; valued and respected, it’s woven into the unique Bali-Hindu culture in tiny elegantly wrapped macrame-like parcels which are placed as offerings to the gods at doorways and temples to appease the demon spirits, Bhuta and Kala, and the blood-sucking goblins, witches and giants of the night. Blood and guts make up a true part of the Bali diet. Lawar is a coconut-chilli-shredded salad, its dressing - blood. Along with fried chicken, the tourists popularize mee goreng (stir-fried noodles) in all its variations. Numerous species of sea and freshwater fish are landed every morning and flogged from Jimbaran’s open market or from baskets on the beach. Vanilla beans can be found growing in the volcanic mountains of Bali. Though most of the population is Muslim, Balinese Hindus eat pig, as do Torajans of Sulawesi, who go in for buffalo feasting at festive and funeral occasions. Buffalo are slaughtered in front of guests. Invited to stay for one such blood-bath, I declined after the first animal went down - and stuck with fish for the rest of my trip.