Advertisement

Sweets And Desserts

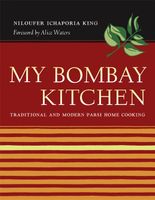

Published 2007

Sweets are a regular punctuation mark in every Parsi life. Auspicious days, whether personal or religious, are usually celebrated with the distribution of sweets, and all the days in between are improved by their consumption. On birthdays, it gets even better. Breakfast consists of one of the required sweets, such as sev or rava, with sweet yogurt. Lunch will probably involve a special “pudding,” as we still call desserts, following the English pattern. Teatime brings a birthday party and a birthday cake. More sweet treats such as chocolates end a birthday dinner party. Seven months into a pregnancy? You send around a conical sweet called a ladva to friends and family. If there’s an unmarried girl in the house, she gets to pick off the tip. (A friend’s permanently unmarried state was once attributed to her father’s picking off the ladva point before she got to it.) Pass an exam? Parents send around sweets. Move into a new place? More sweets to be sent around. The festivals of other religious communities in Bombay are also occasions for sending and receiving sweets, which often arrive still warm at breakfast time. Sweet making and sending are among the perfect expressions of Bombay’s nondenominational food culture. Each community has special sweets prized by all the others. Hindu sweet makers are known for their halvahs, barfis, jalebis, and gulab jamuns (golab jam in Gujarati); Muslims for luscious cream pastries called malai na khaja, and other extraordinary things called aga hi dahri (“holy man’s beard”) or ba-galyu (little stork”), feathery and flaky; Parsis for ladva and penda; Goan and Irani bakeries for fruitcakes.