Advertisement

Producer Profile: Nikki Rothwell

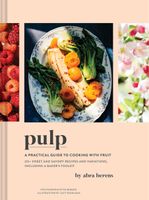

By Abra Berens

Published 2023

Dr.

Abra Berens: Years ago you told me that if someone isn’t born into a cherry growing family, they basically can’t become a cherry grower. Can you explain that?

Nikki Rothwell : Specialty crop farming requires a lot of initial investment, particularly if you are new to the game (i.e., not born or married into a fruit farming family). Land prices in northwest Michigan are extremely high. Next, planting trees is expensive in terms of money and time. Right now, nurseries cannot keep up with demand. To plant dwarf apples in a high-density situation (which should always be done given all the research and economic work) is a two- to three-year wait. Once you have the trees, costs run $20,000 to $25,000 per acre. Tart cherries are much cheaper to plant, but we do not mechanically harvest those trees until they are physically big enough to “shake,” which in most cases is six years—six years of spraying, pruning, mowing, etc., with no returns—time and money. A shaker runs about $180,000; to justify a specialized piece of equipment like that, you need a lot of acres. With the tart cherry industry at somewhat of a crossroads (between import pressure, invasive insects, climate change), everyone assumes grapes, or some other crop, will be better. However, transitions take money—grapes (the media darling as a cherry successor) are also $20,000 per acre to plant and take a few years to get into production. The other thing that people don’t consider is that wine grapes are very similar to tart cherries … both are grown by growers, but are paid by processors at the amount they want to pay. Winemakers and cherry processors are the ones buying those commodities and basically setting the prices. If the grower is vertically integrated, that’s another story, but that’s more investment.