Advertisement

A Few Words About the Local Wines

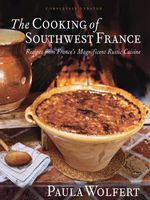

Appears in

Published 1987

The wines of the Southwest include some of the greatest and most illustrious ever produced, as well as hundreds of brands never seen beyond the bounds of their domains. Bordeaux wines are readily available in the United States and are the classic accompaniments to many dishes in this book. For an excellent treatment of the great whites and reds of Bordeaux, I refer readers to

Madiran, an intense, solid, inky, and very tannic wine, is often the choice on the Gascon table. Made from Tannat grapes, often blended with Cabernet Sauvignon, Madiran keeps well and improves markedly with age. It has recently become more widely available in the American market and pairs wonderfully with the rich, hearty food described in this book. When a Madiran is unavailable, try a hearty Syrah from the Rhône Valley, such as Cornas or Hermitage, or an earthy old-vines Zinfandel from Amador County in California.