Advertisement

Sugars

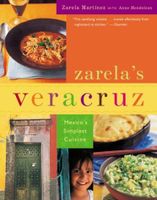

Published 2001

All along the Gulf coast of Mexico (indeed, in all sugar-growing parts of the Caribbean and Latin America), this sight used to be varied by the small-scale artisanal sugar mills that dotted the countryside. These simple facilities, or trapiches, ground the harvested cane and boiled the juice in a series of evaporating pans. Few trapiches are left now, but their tiny output is highly prized by Veracruzan connoisseurs who know sugars as substances full of fascinating nuances, not standardized sweeteners. At every stage of boiling, there is a different balance of pure sucrose and the many cane-juice residues. At the end of the process, the unclarified molten sugar is poured into molds where it hardens into brown loaf sugar. The syrupy residue (molasses, the fraction of cane juice that won’t crystallize) is equally valued. It is not identical to our commercial molasses, because it is not as completely separated from the sucrose. This delicious cane syrup, known as miel decaña or just caña, is the wonderful accompaniment to many a Veracruzan pastry.