Advertisement

Mason Jars

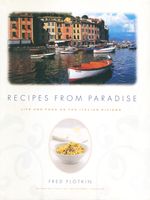

By Fred Plotkin

Published 1997

A hand-carved wood stamp for corzetti

Ligurians go Food Shopping through the Centuries

Among the most enjoyable aspects of my research for this book was that I was granted special access to the Archivio dello Stato di Genova, the State Archive of Genoa, which I frequented for six months.

One particularly intriguing detail always delighted me. Whenever a document was brought to me for my perusal, whether it had been examined by someone else the day before or two hundred years before, it was invariably closed with a string tied in one of the many sailor’s knots that are used by Ligurian seafarers (rather than with a simple knot that you or I would use to tie a shoelace or a ribbon). I realized from this very subtle detail that this particular thread in the Ligurian social fabric had endured for centuries.

What impressed me in my research is that the upper classes, whether noble or mercantile, tended to buy foods that were not terribly different from what was consumed by the poor. The only difference was the greater variety found on the shopping lists of people with more money.

For example, on a typical day in the life of the family of Cammillo Pallavicino in 1668, they might acquire fish; 12 oysters (this is more unusual); 12 artichokes; milk; cabbage; cauliflower; pine nuts; raisins; sapori e foglie (flavors and leaves, that is, spices and herbs); lettuce; 2 eggs; salt. When the Pallavicinos made a bigger shopping trip to acquire staples for the larder, they would buy sausage; cardoons; butter; 12 eggs; sugar; cinnamon; raisins; dry biscuits for dipping; lard; fideli (string pasta); milk; and a prepared meal for the servants.

By contrast, the Libro del Introito del Convento (a book of purchases by a convent in Genoa) reflects a more austere approach, but hardly deprivation. In February 1696, the nuns bought meat; fish; eggs; cheese; cod; sugar; salt; and sausage. In April of the same year, they bought much of the same, with artichokes and chestnuts added. Things must have improved by October 1698, when the nuns bought meat; fish; eggs; prescinseua; salt-cured fish; mushrooms; rice; bread; fideli; vinegar; garlic; spelt; and four types of wine. I wondered at the almost complete absence of fruits, vegetables, and herbs from the nuns’ diet. Further reading revealed that within the walls of the convent was a splendid garden that yielded all the produce they could require.

From the 1732 book of expenditures of the Spinola family one of Genoa’s most exalted clans, there is more space devoted to prepared foods than one previously encounters. This indicates that by this time Genoa had cooks in stores who created finished dishes for home consumption. So the Spinolas bought onion tart; sweet cake; cuttlefish antipasto; ravioli; cooked tomatoes, spinach, lasagne, and liver; roast beef; roast veal; meatballs; stuffed lettuce leaves; boiled cod; fried fish; stuffed mushrooms; pea sauce; sauce for cornetti (probably the Pine Nut-Marjoram Sauce); macaroni with mushrooms and sausage; simma piena (cima ripiena); and “soup for the servants” (on Sunday they were served beef).

Additionally, the Spinolas kept a very rich pantry: rice; bread; chestnuts; cinnamon; onions; bottarga (dried tuna roe); salted fish such as anchovies; eggs; salami; pine nuts; dried chickpeas; salt cod; tuna; squash; fennel; sage; pepper; garlic; dried peas; dried mushrooms; olive oil; fideli; almonds; figs; and lemons.

A separate entry was made for foods that were donated to a nearby convent: capons; wine; biscuits; and chocolate.

A convent in Ventimiglia in 1802 had a rather ample shopping list, one that makes one wonder how the sisters passed their days: pasta; hazelnuts; stockfish (spelled Stockefix); rice; goat; salt; “Dutch cheese” — imported Gouda; Pecorino cheese; bread; fava beans; eggs; tuna; whitebait; chickpea flour; wine; cabbage; pork; anchovies; lard; saffron; “many, many” dried mushrooms and sardines; shoes; tobacco; needles; incense; candles; and soap.

In an 1804 listing from the same convent I found the only purchase, in all of my research, for “una mescolanza dall’orto,” or a mixture of vegetables and fruits from the garden. Apparently, vegetables, fruits, and herbs existed in such profusion in Liguria that they did not have to be purchased. We know this because documents of meals of the past indicate extensive consumption of vegetables, herbs, and fruit.