Composed Salads

Salades Composées

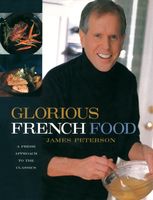

Published 2002

- How to Combine Vegetables, Meat, or Seafood into Inventive Salads

- More Ideas about Salad Sauces

- The Difference Between Truffle Oil and “Truffle Juice” and How to Make your own Truffle Oil

- How to Peel Asparagus

- How to Trim Artichokes

A salade composée is a salad in which various cold ingredients are cut, usually into cubes, and tossed together in some kind of cold sauce. What the French call salades simples contain only one central ingredient, such as carrots, cucumbers, mushrooms, or string beans, and are often served together as an assortment for a crudité platter. Green salads, of course, may have any number of ingredients tossed with the lettuce, but it’s the greens in the salad that set the tone. A composed salad may contain greens but they’re often just decorative and are rarely the main element. Usually a composed salad consists of vegetables and sometimes meats or seafood tossed together in a mayonnaise, vinaigrette, or occasionally a cold cream sauce. Many of my own composed salads are based on leftovers. If I’m cooking to impress, I’ll run out in search of ingredients to combine with my leftovers, but otherwise and when feeling lazy, I’ll just toss leftover vegetables, or strips of leftover meat or fish, with a little olive oil, vinegar, salt and pepper, and a few herbs from the garden. In old French cookbooks, salads made by combining ingredients carefully cut into cubes (macédoine) are sometimes called salades macédoines or salpicons, but I like to leave the natural shape of the salad ingredients as intact as possible. When combining ingredients in a composed salad it’s hard to go terribly wrong, and in fact combinations that at first Sound odd often reveal themselves to be surprisingly good (although I’ve yet to try a pineapple and truffle salad mentioned in Proust). It’s helpful, though, to keep in mind certain principles. Much of the time you should be able to taste all the ingredients in a composed salad without one or two taking over the flavor of the whole thing. On the other hand, especially if you’re showing off special ingredients like cooked lobster or crayfish, there shoudn’t be too many competing elements. As when inviting guests to a dinner party, you want a happy blend of talkers and listeners. One flavor should predominate but not dominate. (If, for example, I’m making a salad containing lobster, I’ll probably work some of the lobster coral into the sauce so the salad all tastes of lobster but not so strongly that I can’t taste other ingredients through the sauce.) Texture is also important. Salads containing relatively soft ingredients such as cooked beets or potatoes usually benefit from other ingredients of contrasting texture. This contrast can be subtle—cooked artichoke bottoms aren’t terribly firm, but they still have more texture than potatoes—or the contrast can be made dramatic by adding something distinctly crunchy like roasted walnuts or pecans. The richness of ingredients should also contrast. A salad of peas, green beans, and asparagus can function as a backdrop of richer ingredients such as strips of prosciutto or even cubes of foie gras. Starchy ingredients such as rice, potatoes, and pasta benefit from lightly crunchy greens. Cubes of cheese are surprisingly good with sweet and crunchy pieces of apple.

Become a Premium Member to access this page

Unlimited, ad-free access to hundreds of the world’s best cookbooks

Over 160,000 recipes with thousands more added every month

Recommended by leading chefs and food writers

Powerful search filters to match your tastes

Create collections and add reviews or private notes to any recipe

Swipe to browse each cookbook from cover-to-cover

Manage your subscription via the My Membership page

In this section

Advertisement

Advertisement