Advertisement

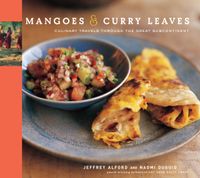

The Ghats

Appears in

By Jeffrey Alford and Naomi Duguid

Published 2005

It was a hot season, late March. I was in Varanasi (formerly Benares, in northern India, one of the oldest and holiest cities in the Subcontinent), staying in the crowded and intense old town, in a guesthouse that overlooked the Ganges. Before dawn every morning, just below my window, I’d see people in ones and twos walking along the embankment above the river. They were heading to one of the ghats, places where stone steps lead down to the water. I’d hurry over there, too, to watch the action.

By the time the sun came up, the ghats were very lively: There were priests and offering vendors and tea sellers and astrologers, all there because every day hundreds of people come to bathe in the Ganges and pray and make offerings. The Ganges has long been a holy river for Hindus, who believe that the river water has cleansing and curative powers and that bathing in the river—or being cremated and having one’s ashes tossed into the river—is a religious act that can help free one from the cycle of suffering and rebirth. The bathers make their way down to the water, leaving a bundle of dry clothes on the steps, then stand waist-deep in the river in their saris or sarongs, splashing water on themselves, alone or with friends and family, praying and making offerings. Then they come back up the steps to dry off and change, always staying modest and covered, before climbing the steps to the top of the embankment and back to the world.