Advertisement

Author Profile: Marlena Spieler – The Complete Guide to Traditional Jewish Cooking

6 July 2021 · Behind the Cookbook

“I wanted to make sure that as many different groups and communities’ dishes were cooked and portrayed as possible.”

Q&A with Marlena Spieler

Food writer and broadcaster Marlena Spieler was born in Sacramento, California and is now based in Hampshire in the UK. She has written more than 70 cookbooks, many inspired by her travels, in which she revels in seeking out fascinating stories that link food and culture.

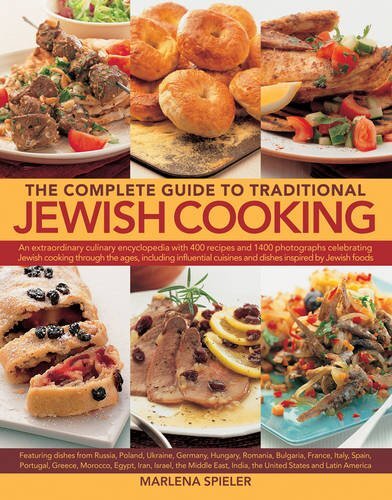

In the monumental work, The Complete Guide to Traditional Jewish Cooking (2006), Marlena turns historian and storyteller to explore “a cuisine that is as diverse as it is delicious”. This compendium of Jewish culture and cuisine follows the Jewish Diaspora across Europe, Central Asia, the Middle East, Africa, China, Latin America, the Caribbean and the US, explaining the customs, traditions and recipes that unite Jews everywhere.

In 2011, Marlena lost her sense of smell (anosmia) after suffering from a head injury in a car accident. We spoke to Marlena about Jewish traditions that matter most to her personally and how she has had to start from scratch again in her understanding of flavor.

Q: What can you remember about the process of writing the book?

A: I’ve written so many cookbooks and it’s just something I love doing. There’s a beginning and there’s an end. And they aren’t really beginnings and ends, but to your project they are. And in between there’s so much to gather, so much to cook, and so much inspiration. I love to follow the dots and the story.

Back in 2005, Anness Publishing wrote to me and said would I consider writing a comprehensive book about Jewish cuisine? At the time my brother had just died suddenly and my grandmother had also just died and my brother and I were close to my grandmother. And I said yes. Yes, yes, yes. It brought me closer to my brother and to my grandmother. I just felt that there was this connection. It was quite emotional. It made me feel so much better. I wanted to make sure that as many different groups and communities’ dishes were cooked and portrayed as possible. Jews have lived all over the world, except when they can’t. It’s very moving.

Q: You write in the book about dishes that have particular significance to mark religious festivals and the symbolism of the ingredients. What are the most important food rituals to you?

A: Well, there are so many! Where do I start? Latkes, Potato Kugel, all sorts of sweets that are fried. At Chanukah, the frying symbolizes the oil in the eternal light which was meant to last only one day at the rededication of the temple after its destruction, but instead, it lasted eight days, long enough for the new oil to arrive. At Purim there’s Hamantasche, which are these triangle pastries. The three-cornered shape is meant to symbolize the three-cornered hat of the villain of the event: Haman. Oh my god, they’re so good! They’re filled with fruit, but you could fill them with chocolate. But here’s the thing that I think is the biggest event of the year, ritual-wise, the Pesach Seder [Passover Seder].

Seder is the name of the ritual meal and the word “Seder” means “Order” as in the order of everything. The meal tells the story of this ragtag tribe fleeing the Pharaoh’s army in search of freedom. The story is for everyone. No matter who, no matter where. The ritual and prayers, meanings, and history/story is laid out in the Haggadah, that is, the book that is read throughout the course of the evening. It’s said that you should feel as though you were actually there – it’s you who is fleeing Egypt in search of freedom.

Of course, every community has its own little things and when my brother was married to an Iranian Jew, one of their Seder rituals – and I love it so much that it’s been part of our family Seder ever since – is that when you speak of the Pharaoh’s army being so cruel and beating the slaves when they weren’t working hard enough, well... everyone takes a spring onion or two and beats each other with it. You have to use the green ends as the white ends could hurt you! It’s hilarious. And it’s a Persian thing – I’ve never found it any other place. Kids love it. Adults love it. The room starts smelling like onions and it’s really fun.

Q: This ritual must have been difficult for you when you lost your sense of smell after a car accident. We can’t begin to imagine the challenges for you as a cook and food writer. How has this anosmia affected your work and your identity, which is tied so intrinsically to cooking and writing about food?

A: At first nothing had any taste. Nothing. This was so alarming. I didn’t know what was happening. No one was any help. We didn’t have online resources. Everything was empty, horrible. The tastes that eventually returned were flat and unpleasant and I didn’t know what to do. Because when I tried to eat, it would break my heart. Then, just as the anosmia was starting to lift a bit, I started getting these distortions called parosmia and phantosmia.

But yes, at Pesach, one of my favorite moments was when we would beat each other with the spring onions, and the room would smell of them. Because I didn't want to make whoever was sitting at our table feel bad, I kept the anosmia to myself. The room felt so empty; I could see the spring onions, I knew they smelled amazing, they conjured up Pesachs past, but without smelling them myself. I just felt sad. I didn't know if I'd ever smell again.

Smell and taste is the biggest motivation for my cooking, and for sharing by writing about it. Why do I love writing cookbooks? It’s because I love concocting the dishes and making things that are so delicious and that smell good.

Anosmia is when you can’t smell anything, parosmia is the distortion of things that are really there and then there’s phantosmia, which is just like parosmia but it’s things that aren’t there. Like my phone. My phone always smells weird. It could smell like barbecue. It could smell like springtime. It could smell like flowers. It could smell like grilled cheese sandwiches!

Q: That sounds so weird and scary, but also intriguing. What did you learn about yourself and about cooking from this experience?

A: One thing the whole experience has taught me is that I’m a better cook in some ways because I’m less attached to the way I think things should be. Because I don’t even know how things should be now! It allowed me to meet all my flavors for the first time, over and over and over again. Lucky me to have had it for so long - I’m now writing a book about my experiences of it. Because it is so frightening and inexplicable, I hope my own experiences might help others.

Q: So back to the wonderful and varied flavors of ‘The Complete Guide to Traditional Jewish Cooking’. What are your highlights of the book?

You have to try the Libyan Spicy Pumpkin Dip – all of North Africa has these vegetable dips, you know, a sort of vegetable moosh. They have various names in Morocco, Tunisia, all of North Africa does. Sometimes they’re made from carrots or aubergines or pepper. But the pumpkin (or you could use Hubbard squash) is so delicious! I fell in love with this dish in Jaffa in Tel Aviv in a famous café called Dr. Shakshuka run by a Libyan family. My daughter had led me there because she had been doing a medical residency at Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem and I went to the restaurant and talked to the people there about their community. So I just started making it with my taste memories – this was before the accident.

And there’s Chicken Soup of course. Jewish penicillin. My grandmother made the best. Everyone’s grandmother - especially if they’re a Jewish grandmother - if they made chicken soup, they made it the best. So this is my grandmother’s and it’s beautiful. You eat it at the Pesach Sedar and you eat it at Shabbat. When somebody’s sick, Chicken Soup is the miracle cure. And the Knaidlach, the matzo balls that go with it. Everyone has their favorite. Light and fluffy? Hard like a rock? Big? Small? Do you put other things in it? I like herbs in mine. Nothing to me says being Jewish than a bowl of chicken soup! And my husband – he’s not Jewish – absolutely loves my grandmother’s chicken soup (and, in fact, makes it himself and it’s really good!)

I like every dish to have a story. For instance, here in the UK, we have fish and chips. It’s well known these days that it originated in the East End of London but I was the first one who found that in various sources from Portuguese Jews, the first Jews to come back to England after being expelled were Sephardi. They came from the Netherlands (where they had migrated post-Spanish expulsion. They fried fish. It was pareve [permitted in the dietary laws of Judaism]. Probably the fish originated with the Portuguese who might have brought the frying technique from Japan or China. In the East End, they added potatoes and the meal became filling, and warming, and was something that the Jewish workers in East End sweatshops could eat.

Fried fish is believed to have been brought to Britain by Sephardic Jewish refugees.

Q: So many influences! Your book covers such diverse food from all across the world. Jewish cooking is really a history of the world’s cooking. Which food communities are you still exploring?

A: Yes, Jewish people have been everywhere! There are Ashkenazi from Eastern Europe, which includes my grandparents. Then there are the Sephardim, but then there are all these other groups. For example, in Ethiopia. What a community! If you like spicy food, it’s so good. There’s a wonderful community in Israel of Ethiopian Jews. There are also Rwandan Jews, and have been many different Jewish communities throughout Africa. Iraqi Jews had a huge influence on British culture, and their food is amazing.

I have a friend whose close family escaped Germany to Mexico before they could get into America and she grew up with her grandmother. She thought that various Mexican specialties like moles were Jewish. Because, of course, her grandmother made them, they had to be Jewish!

Jews settle, adapt their dishes to kashrut [permitted to eat], bring along dishes from the last place they lived if applicable, and then if they are forced to leave, they recreate the recipes in their next home, sharing flavors and ingredients along the way. Really it’s preserving your culture. So whenever I found a community that was no longer there, but had left behind some tasty dishes that everybody was eating, then I just felt like they came back to life. Taste is so important, so it really kind of hooks up. By losing my taste and my smell I could understand so much more about the cultures around me and the culture I came from.

I could have lived without the anosmia happening, but in some ways, it’s actually a gift. I can’t believe I’m saying that. I never thought I would. So many people have also lost their sense of taste and smell during the pandemic and thankfully there are now resources to help, such as the wonderful network AbScent.

You can find every recipe from The Complete Guide to Traditional Jewish Cooking on ckbk, in full. See Marlena’s collection (previewed below) for a selection of the author’s favorite recipes from the book.

Sign up for ckbk's weekly email newsletter

More ‘Behind the Cookbook’ stories

Advertisement