Advertisement

Tamarind

Appears in

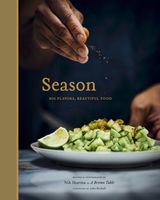

By Nik Sharma

Published 2018

Tamarind is a tropical fruit that’s typically used in African, Asian, and Mexican cuisines. Some producers label tamarind “sour Asian” or “sweet Mexican,” which refers to the stage at which the fruit was harvested. The longer the fruit ages, the sweeter it gets. I usually stick with the sour variety and then sweeten as needed.

Tamarind is available in four different forms: the whole fruit in the pods (top left); a wet, seedless cake of pulp, which some producers call “paste” (top right); a dried block of pulp with seeds (bottom left); and a liquid concentrate with a dark, molasseslike color and texture (bottom right). The dried pulp and the wet paste are basically the same thing. You can use either one for the recipes in this book. Avoid the liquid concentrate, though, because it’s been cooked down, it doesn’t taste the same. (I find it a little off.) Working with the fruit or the seedless cakes at home, it’s very easy and requires only a short amount of time. If you buy the whole fruit in their pods, remove as much of the shell as you can and follow the instructions in the recipe for softening it in boiling water and straining the fruit, which will take care of any pieces of shell.