Label

All

0

Clear all filters

🔥 Try our grilling cookbooks and save 25% on ckbk membership with code BBQ25 🔥

Beware of Camels

Appears in

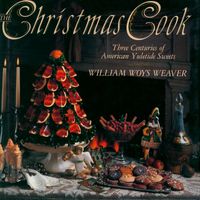

Published 1990

- 1. Hannah Glasse, The Art of Cookery (London: Printed for T. Longman, 1796), 310.

- 2. Christmas with the Girls (Philadelphia: American Sunday School Union, 1875), 23-24.

- 3. The Household (Brattleboro, Vt.) 7 (September 1874), 205.

- 4. Hans Wiswe, Kulturgeschichte der Kochkunst (München: Heinz Moos Verlag, 1970), 211-12.

- 5. Thomas Cooper, ed., The Domestic Encyclopedia, 3 (Philadelphia: Abraham Small, 1821), 477.

- 6. John Y. Kohl, “Christmas Cookies—A Controversy. Proceedings of the Lehigh County Historical Society” 22 (1959): 79-164.

- 7. The Family Receipt Book (Pittsburgh: Randolph Barnes, 1819), 164.

- 8. One of the best European studies is Albert Walzer’s Liebeskutsche, Reitersmann, Nikolaus und Kinderbringer (Konstanz/Stuttgart: Jan Thorbecke Verlag, 1963).

- 9. The Confectioners’ Journal 25 (September 1899): 14.

- 10. J. H. Kuhlman, Holiday Help (Loudonsville, Ohio: J. H. Kuhlman, 1917), 18-19.

- 11. The interplay of these images is analyzed by Ernst Guldan in his Eva und Maria (Graz/Köln: Verlag Hermann Böhlaus Nachfolger, 1966).

- 12. The Confectioners’ Journal 25 (January 1899): 110.

- 13. Helen R. Martin, Tillie, A Mennonite Maid (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1904).

- 14. Maria Sophia Schellhammer, Das branden-burgische Koch-Buch (Berlin/Potsdam: Johann Andreas Rüdiger, 1732), 353.

- 15. It was printed at Einsiedeln, Switzerland, by the firm of Benziger & Company, which began issuing these pictures in 1801.

- 16. Phillip V. Snyder, The Christmas Tree (New York: Viking, 1976), 26-27.

- 17. Discussed thoroughly by Christa Pieske in her Das ABC des Luxuspapiers (Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag, 1983), 189-192.

- 18. J. J. Schilstra, Prenten in Hout (Lochem: De Tijdstroom by, 1985), 164-83.

- 19. One of the earliest appearances of the word cookie in print may be found in the New York Daily Advertiser for 20 March 1786.

- 20. J. H. Spitzbub of Philadelphia, for example, advertised a large variety of imported German Christmas goods, including Nürnberg toys, gingerbreads, and wooden horses in the United States Gazette, 9 November 1807.

- 21. There is a large collection of these molds in the collection of the Deutsches Brotmuseum in Ulm, West Germany.

- 22. Allen’s Supply Buyers News (Chicago: J. W. Allen & Co., 1926), 3.

- 23. Practical Housekeeping (Minneapolis: Buckeye Publishing Company, 1884), 488.

- 24. Good Housekeeping, March 1915, 99.

- 25. United States Gazette (Philadelphia), 28 December 1840.

- 26. C. H. King, “Crackers and Biscuits,” Bakers’ Helper (January 1898), 37.

- 27. The Original Buckeye Cook Book (St. Paul: Webb, 1905), 83.

Become a Premium Member to access this page

Unlimited, ad-free access to hundreds of the world’s best cookbooks

Over 160,000 recipes with thousands more added every month

Recommended by leading chefs and food writers

Powerful search filters to match your tastes

Create collections and add reviews or private notes to any recipe

Swipe to browse each cookbook from cover-to-cover

Manage your subscription via the My Membership page

Best value

Part of

Advertisement

Advertisement

The licensor does not allow printing of this title