Advertisement

Frances Bissell

Food writer

https://www.serifbooks.co.uk/authors/?book=16Most popular

Features & Stories

Frances's favorite cookbooks

The Cookery Year

A present from my parents, this is the most tattered book on my shelves. A fine combination of recipes, techniques and seasonality, it is also a who’s who of the great food and cookery writers of the day, including Derek Cooper, Margaret Costa, Jane Grigson, Marika Hanbury-Tenison, Kenneth Lo, Katie Stewart and Harold Wilshaw. I began keeping my kitchen diaries the following year.

Hilda’s Diary of a Cape Housekeeper

For a short time as a schoolgirl my family lived on a wine farm near Stellenbosch and it was here that I first tasted food other than Yorkshire home cooking, such as bredies, bobotie, mebos, melktert. Much later, I was thrilled to buy a second-hand copy, which formed part of the late Professor John Fuller’s extensive library, of this elegant facsimile of the 1902 publication, “being a chronicle of daily events and monthly work in a Cape household, with numerous cooking recipes, and notes on gardening, poultry keeping etc”.

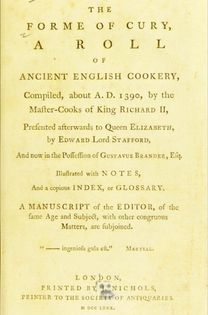

The Forme of Cury

Several scholars have worked on these manuscripts of mediaeval English cookery, including Lorna Sass in 1975 and Constance Hieatt in 1984. In 1986, when I was the cookery writer for The Sunday Times, a whole edition of the magazine was devoted to the 900th anniversary of the Domesday Book. I borrowed an 18th century edition of the work – Warners’ Antiquitates Culinariae - from the London Library to research recipes for a Sunday lunch in a mediaeval household and was hooked forever on early English recipes. To this day I cook tart de Brye.

The Accomplisht Cook

The seventeenth century was one of the richest, most vibrant and exciting periods in English culinary history with fascinating cookbooks. First published in 1660, this is the work of a chef who cooked in the aristocratic houses of England, having been trained by his father, also a chef, in the kitchens of seventeenth century Parisian nobility. Dishes in the “French fashion” abound, as do recipes inspired by sources as diverse as Turkey, Poland, Portugal and Italy. In true chef’s style he also has a penchant for random phonetic spelling, which I find very endearing. Thus on one page we have, for halibut, both “hollyburt” and “holyburt”. Most of all, I like his recipe for “wivos mequidos”, none other than a dish of “huevos” or eggs “in the Spanish fashion”. Apart from the extreme deliciousness and ‘cookability’ of many of his recipes - lemon cream flavoured with orange flower water, little Portuguese sponge cakes flavoured with rosewater, a lobster pie, a very fine rice pudding, a crayfish pottage, some interesting ways with veal including small veal or chicken pies and delicious oyster pies and oyster jellies which have become part of my own culinary repertoire - I find the book enormously comforting in that it demonstrates what I have long held to be true. There has not been a revolution in the British kitchen, merely an evolution. We have been here before.

The Classic Italian Cookbook

Adapted by Anna Del Conte. Here, for the price of one, we have two exceptional Italian writers and cooks. Long before there were telly chefs, travelling the length and breadth of the country, there was Marcella, and there was Anna. In limpid prose, with clear instructions, absolutely authentic and gimmick-free, some of the vast repertoire of Italian cooking is revealed, with charm and elegance. I cannot leaf through the book without wanting to go and cook. I would not dream of using any other recipe for ragú. Who needs pictures?

The Alice B Toklas Cookbook

Serif's 1994 edition is a more attractive book than the 1984 Harper & Row US Edition –although I should declare an interest here. The late and much missed Stephen Hayward of Serif Books published my books on floral cooking which, like the Toklas, were also designed by Pentagram. The contents are as delightful as the cover is elegant, with a fine sense of time and place, of France before and during the Second World War, and some serious name dropping, describing kitchen suppers for Picasso.

Modern Cookery for Private Families

It was either Miss Acton or Prospect Books’ facsimile edition of Hannah Glasse’s The Art of Cookery but in the end it has to be the writer cook who paved the way for us all, in a sense, because Eliza Acton was the first to write down a recipe in the formula with which we are familiar today, including a list of ingredients, a detailed method, observations and cooking time, and recipes which were designed to be used in the home, every day, rather than restaurant or banquet food. Published in 1845, Acton’s food is extraordinarily modern and her writing is detailed to the point of being an extremely good read.

The Way to Cook

If I were to recommend one book to an aspiring cook, this is it. Each section has a master recipe, several examples, with variations, notes on equipment, on ingredients and on time planning, as well as Julia’s cheery prose which entices us to cook. It is so comprehensive that there is plenty here, too, for the experienced cook. This is the book Julia was working on when I first met her, after which I had many happy hours with her in her kitchen in Cambridge, as well as on shopping expeditions to farmers markets. With this book, anyone can “master the art of French cooking”.

Summer Cooking

I love this book for its evocation of the very hot summer of 1976 when I bought it on my way home on a breathlessly sultry day in London. The idea of chilled lettuce soup, little cold filled omelettes and all manner of cooling desserts is appealing today as it was then. As I write this in a less than sultry month of June, I see that these dishes did, indeed, figure in my kitchen diaries in summer 1976, accompanied by some amazing 1971 hocks.

Food in England

Just wins out for the last place in my list over Good Things in England by Florence White because it tells an important story. She lived at a time when it was possible to remember England as a more agricultural society, and the roots of our culinary traditions. As the notion of seasonality, provenance and localness becomes increasingly important, Dorothy Hartley’s work can be a source of inspiration to us all, cooks, chefs, food writers, retailers and producers alike.

Advertisement