Label

All

0

Clear all filters

Cold, hot, real or artificial

Appears in

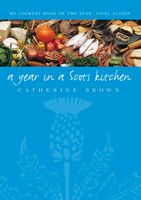

Published 1996

What to do was salt first. That kept the bugs at bay, for a while. But long-term the idea was to hang food from smoke-blackened rafters for at least one winter, if not two. During which time the cool peat smoke wafting upwards from the open fire in the centre of house also smoke-blackened the food. Between the salt and the smoke there would be a lively appetite-rouser when the need arose.

Now food is salted and smoked for a shorter time and not from rafters. But modern methods have the same effect of producing new flavour compounds in food when the aromatic acetates and aldehydes in the cool smoke vapour combine with salt in the flesh. So long as the smoke is not too hot and the food does not ‘cook’, the new smoky flavour will travel gradually through the food, altering its colour and flavour. But if the smoke cooks the food, the flavour will settle mainly on the surface, as it does in an Arbroath Smokie, or a barbecued steak.

Become a Premium Member to access this page

Unlimited, ad-free access to hundreds of the world’s best cookbooks

Over 160,000 recipes with thousands more added every month

Recommended by leading chefs and food writers

Powerful search filters to match your tastes

Create collections and add reviews or private notes to any recipe

Swipe to browse each cookbook from cover-to-cover

Manage your subscription via the My Membership page

Best value

Part of

Advertisement

Advertisement

The licensor does not allow printing of this title