Advertisement

Behind the Cookbook: James Peterson on Glorious French Food

4 March 2020 · Behind the Cookbook

My Missing Chef d’oeuvre: Glorious French Food

While Sauces has garnered the most attention, my magnum opus is Glorious French Food. While it won a James Beard Award, it was ignored by the press. Keep in mind that in those days before social media, “the press” was all we had. The book came out on the day the United States invaded Iraq. The French had refused to go along, so many Americans, patriotic about the war, came up with such absurdities as “freedom fries.” French was out.

In addition to the whole freedom fries thing, there was an underlying consensus that French food contained too much fat.

When I set out to write Glorious French Food, two years before, it was my purpose to restore French food’s reputation as providing a well-rounded and healthy diet, and to demonstrate how inextricable cuisine is from culture.

French cooking provides the beginning cook with a rigid hierarchy and nomenclature. Such words as mirepoix, brunoise, matignon, and macedoine, have their equivalents in other cuisines, but these cuisines have not developed a rational system for organizing food and technique. It is this organization, propagated by Escoffier in the early twentieth century, Carême in the 19th, and Menon in the 18th, that integrated the culinary traditions of those eras into a workable and predictable framework.

It was the year 2000, and I knew I wanted to write a serious book about French food and cooking. I didn’t want to scare readers off (people were and are afraid of French food) and yet I wanted the book to be complete and thorough. The result was an 800-page monster.

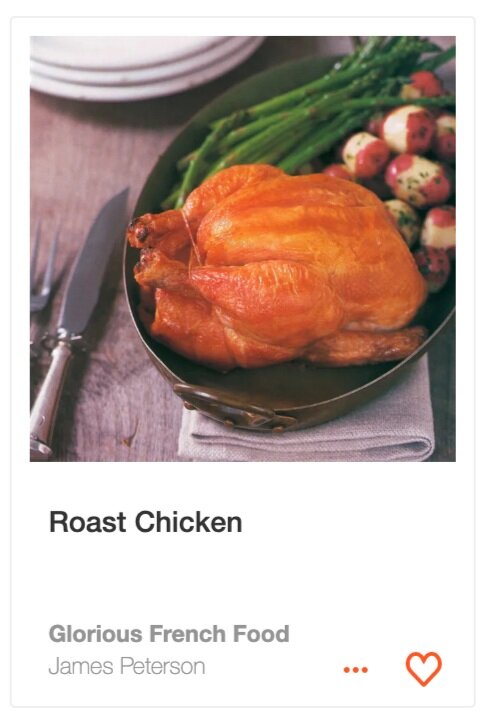

To accomplish this, I used the most familiar French dishes as entry points—dishes like French onion soup, crèpes suzette, and pâté. The chapter on duck à l’orange, for example, not only discusses and gives a recipe, but uses the techniques for the orange duck to make and improvise other dishes along the same vein. Once the basic techniques and principles are understood, the reader is freed up in a way that allows her just to make stuff up.

My process for writing such a book is rather straightforward. I think of an idea for a chapter and the day or evening before writing about it, I walk around and think about it. Sometimes I get ideas when I wake up from a nap. The following morning, I write out the new material and edit the material I wrote from the day before.

Many beginning writers don’t realize that the writing process is entirely different from the editing process. They try to correct and make it perfect as they go along and, by doing so, make little progress. When I’m writing, I just write what I want. Sometimes I even write things that I know will be taken out, just because they must be written. If I try to edit my work during this expansive creative process, I end up in confusion and kill the work. It’s essential to allow yourself to write what comes up, even if it seems horrible. Often, I find that “horrible” text, when looked at the next day, isn’t as bad as I thought.

When it’s time to edit, I bring out my red pen and rework the material, sometimes rather extensively. This process eliminates superfluity, smooths the flow of the text, and gets rid of errors.

As the book progressed, I printed it out a third time (a second time just after the first edit) and reread it with the benefit of some temporal distance. Last, I read it out loud, usually while pacing around the room.

People ask how I make up the recipes. The ideas are just there—they never lack—but the recipe, of course, must be written out. I take the same approach as I do with the rest of the writing; I write the recipe, execute the dish in my mind’s eye, and then move on. I return to the recipes during the testing phase after most of the book has been written.

Testing is long, difficult, and expensive. Often recipes work just as described, but other times a recipe must be completely reworked. The principles remain the same, but many times, reintegrating the tested recipe may mean rewriting copy which will then require a new editing process. By the time I turn the book into the editor, I will have read the text ten or so times.

Glorious French Food doesn’t have a lot of photography, but what it does have was arduous to shoot. These were the days before digital cameras; everything had to be shot on film in 4” x 5” format, using a giant, heavy view camera. While this yielded huge beautiful images, the technique was often fraught. The film had to be exposed just so or it would come out too dark or too light. For this reason, I would take multiple exposures to make sure that at least one came out right.

As the project ended, it felt like a factory around here. I’d be shooting with an assistant on one floor while testers worked on another. It was a huge, lengthy, and exciting project. That’s why I want people to read my favorite book.

About the author

James Peterson is an award-winning food writer, cookbook author, photographer, and cooking teacher who started his career as a restaurant cook in Paris in the 1970s. He is the author of fifteen titles, including Sauces, his first book and a 1991 James Beard Cookbook of the Year winner, and Cooking, a 2008 James Beard Award winner. He has been one of the country's preeminent cooking instructors for more than 20 years and has taught at the Institute of Culinary Education in New York. He is revered within the industry and highly regarded as a professional resource. James Peterson cooks, writes, and photographs from Brooklyn, New York.

Books by James Peterson on ckbk

by James Peterson

Expand your repertoire with this all-inclusive handbook, a trusted reference and confidence-booster for kitchen neophytes. 1,500 vivid instructional photographs accompany James Peterson’s carefully distilled classics, gleaned from a cook’s tour of professional kitchens, such as roasted chicken, bouillabaisse, and apple-pie.

by James Peterson

This master class in pastry making caters to both novice bakers and cake bosses. Culinary coach James Peterson presents the basics, such as moist sponge cake and devil’s food cake, along with ambitious showstoppers, like a Peach Crème Mousseline and Chocolate Hazelnut With Hazelnut Buttercream, dressed with meticulous illustrations and photographs.

by James Peterson

This single-subject cookbook, packed with instructional photographs, pledges allegiance to everybody’s favorite fish. Renowned writer and culinary arts teacher James Peterson kicks off with the basics—what to look for when buying fresh salmon; the differences between wild and farm-raised; how to clean, bone and cure, etc.—before presenting revised classics, like Salmon With Tarragon Butter and Salmon en Papillote.

by James Peterson

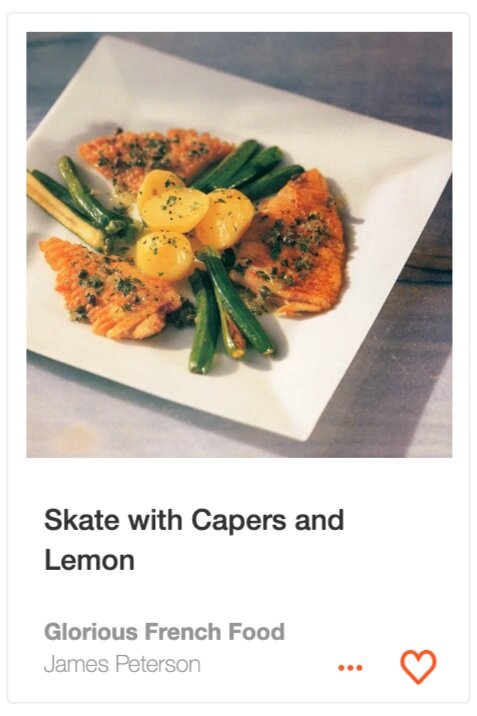

James Peterson gives second lives to timeless French stalwarts like cheese soufflé, which gets treated to a twice-baked mushroom version, and crème brulee, which served as the inspiration for Peterson’s orange-flavored crème caramel. But it’s the astute observations about each dish’s history and evolution that distinguish this comprehensive and sophisticated resource.

by James Peterson

Every good cook knows that a great sauce is one of the easiest ways to make an exemplary dish. Since its James Beard Award–winning first edition, James Peterson’s Sauces has remained the go-to reference for professionals and sophisticated home cooks, with nearly 500 recipes and detailed explanations of every kind of sauce. This new edition, published nearly ten years after the previous one, tacks with today’s movement toward lighter, fresher flavors and preparations and modern cooking methods, while also elucidating the classic sauces and techniques that remain a foundation of excellence in the kitchen. The updated, streamlined design also features, for the first time, full-color photos that clearly show these essential sauces at every step—bringing the author’s expertise to life like never before.

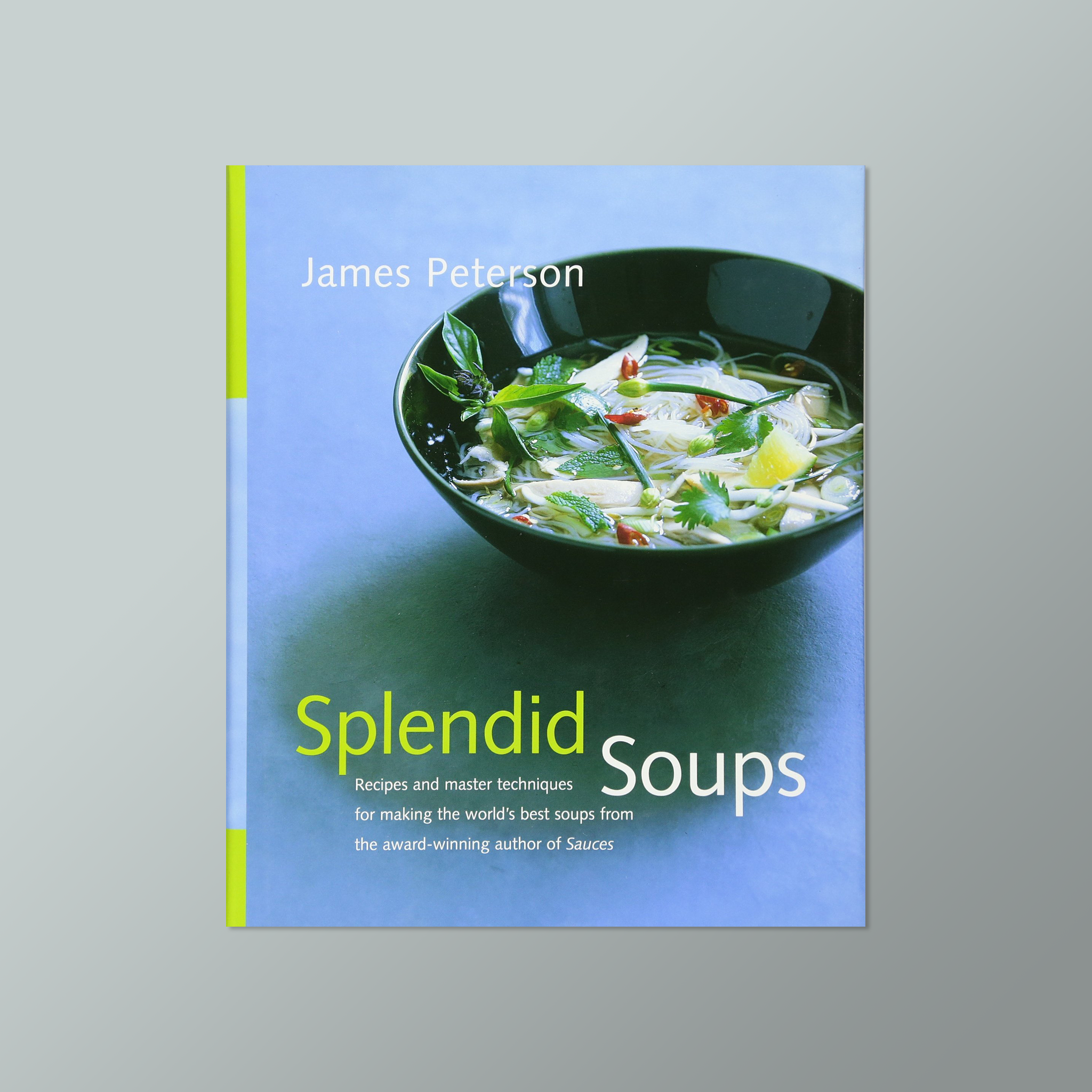

by James Peterson

Francophile chef James Peterson infuses his trademark warmth and passion into 400 recipes for globetrotting brews like Indian-Style Shrimp and Coconut to a classic Gazpacho. For the uninitiated, there’s also an introduction to broth and consommé-crafting techniques, in addition to advice on selecting the proper pots and utensils.

James Peterson is a featured author on ckbk, home to the world's best cookbooks and recipes for all cooks and every appetite. Start exploring now ▸

Sign up for ckbk's weekly email newsletter

As an added bonus you will receive a free PDF download featuring recipe highlights from our favorite cookbooksAdvertisement