Advertisement

Behind the Cookbook: The Authentic Pasta Book

21 November 2024 · Behind the Cookbook

Fred Plotkin is an expert on both Italian opera and Italian food. His regional Italian cookbooks on the cooking of Friuli-Venezia Giulia and of Liguria have already delighted users of ckbk, and we pleased to also now make available The Authentic Pasta Book, his canonical work on real Italian pasta. Below Fred recalls the journey which led to the writing and publication of this much-loved work.

By Fred Plotkin

Back in 1983, when I began to draft notes for the book that came to be known as The Authentic Pasta Book, I was in some ways a different person and the world’s knowledge of the diversity and methodology of pasta cookery was scant most everywhere—even in Italy itself. An Italian might know the traditional preparations of her town or region and perhaps a few of the national classics such as spaghetti with a tomato sauce. But there were even variations from place to place as to what constituted a tomato sauce.

I had lived in Italy for much of the 1970s, mostly in Bologna but also Florence, small-town Tuscany, Rome, Ravello, Pavia, Milan, Trieste and the province of Genoa. I spent a great deal of time in Venice, the first great capital of opera, because most of my education was pointed toward the career in opera (everything but singing) that I had already begun and would continue to expand to this day.

In the 1970s, an American in Bologna was—more often than not—a medical student who did not gain admission to a school in the USA. Bologna had the oldest medical school in the world and was not only a paradise for students but a culinary paradise with amazing markets in which each seller of produce, cheese, meat, fish and other comestibles had extraordinary knowledge of how each ingredient should be used and took pride in selling the very best in the whole market. Food shopping in Bologna was serious business but also joyous and I did it every day. But most of the Americans there never discovered that.

Bologna had the European branch of the Johns Hopkins School of International Affairs, where education was done in English. The Hopkins students lived in something of a bubble and food was available to them. The American medical students lived slightly out of the center and local food shops offered then-exotic items such as peanut butter and corn flakes to cater to Americans who came to Italy by necessity rather than by choice.

I was fortunate to be part of an exchange program at the University of Bologna run by the Universities of Indiana and Wisconsin. We wanted to be in Italy and, moreover, in a place where we had to speak Italian and negotiate the rigors of education Italian-style, complete with strikes, oral exams and dealing with a library system that was rich in holdings but nearly impossible to access. Yet we learned and loved the Italian way of life and few, if any, of us made forays to San Lazzaro to stock up on peanut butter. Most of us lived with Italians, made wonderful friendships and some acquired Italian girlfriends or boyfriends.

Bologna attracted students from all over Italy and most commuted home on weekends or longer and usually wanted me—l’amico americano—to come along. For an Italian, being made welcome in someone’s home is the ultimate gesture of kindness and hospitality, intimacy and confidence. You became part of the family.

Mortadella (Image: Wikipedia)

This was a time without mobile phones—it took years to get a landline—and television only had a few channels. Social life was at the table and people savored what they ate and talked about it with great and opinionated passion. Discussions on trains (everyone conversed on long, frequently strike-delayed railway journeys) centered on food. What did you eat? What are you going to eat when you get home? I quickly learned that I would pack food for six persons (six pears, 600 grams of mortadella) because I would share it with the other five persons in my compartment on the train.

People traveling from elsewhere loved the animated platforms of the Bologna railway station, where you could stick your head out of the train window, proffer a 500 lire bill (about $1) and get a bag with a hot wedge of lasagne verdi alla bolognese, a roll, a piece of fruit and a quarter liter of red wine or mineral water.

In those years I traveled the length and breadth of the Italian peninsula to my many Italian families and went further still to explore villages, landscapes and treasures of antiquity that most Italians had never seen. I came to love the whole country and was dazzled by the linguistic, historical and culinary diversity I encountered from one town and one region to the next. In each place I seemed to acquire an adoptive mother, grandmother, aunt, sister or cousin who was only too happy to show me what she was preparing in the kitchen, including all manner of hand-made pastas. Although the shapes and fillings varied widely, the method of making pasta by hand was quite standard wherever I went.

After doing some initial literature and history courses in Bologna, I enrolled in DAMS, a then-new interdisciplinary performing arts institute at the university that in short order became Italy’s Juilliard. This meant that I not only had Italian friends who invited me to their family homes but invitations to famous and tiny opera houses all over the country to watch and learn and sometimes work on productions. We had to eat—opera builds an appetite—and there was usually a restaurateur in each town who loved opera and wanted visiting casts and crews to sample local specialities in their trattorias and locandas. This was fabulous eating rather than “fine dining” because the food was served with pride and love. I often found my way into their kitchens to learn how things were made. In all my early years in Italy, I never set foot in a cooking school.

Fred Plotkin in Italy in 1979

I did learn recipes from Italian opera colleagues that became part of my kitchen repertoire. Although Luciano Pavarotti was from Modena, he made a masterful version of Rome’s Spaghetti alla Carbonara. I was invited to a family celebration in Padua (in the Veneto) at the home of the wonderful mezzo-soprano Lucia Valentini Terrani and discovered Pasticcio di Maccheroni Padovano, a labor-intensive (but worth it!) pie whose crust contained macaroni, truffles, prosciutto, funghi porcini, cheese, squab, vegetables and wine.

When I returned to New York in 1979, it was my aim to work at the Metropolitan Opera. First I spent nine months in journalism school to reacquire my skills in English and then, soon after, was fortunate to gain employment at the Met. Based on my experience in Italian theaters, I often prepared post-performance pasta suppers for cast members, many from Italy or elsewhere in Europe. At the time, many of the dishes I learned from my Italian families were seldom seen in the USA. A lot of Italian singers said, in effect, “Fred, this tastes like what my mother or grandmother makes. I have never seen it outside of Italy.” They used adjectives such as genuine or traditional or familiar or classic. One word I heard, just once, was authentic.

In 1983 I had the good fortune to come to the attention of Carole Lalli, an outstanding editor at Simon & Schuster, who offered me the chance to write a cookbook. I liked writing but was not a food writer. I was a proficient home cook but not a chef and was not a part of the food world in the US or Italy. Carole told me to write what I know and in my own voice.

I understood, at the heart of the Italian approach to food, that the simplest ingredients achieve harmony and beauty when brought together in classic proportions. I wanted to share the fundamentals of becoming a pasta cook, which meant making sfoglia—the sheets of pasta that can be turned into noodles and filled pastas—by hand. Then it was important to explain how pasta (whether fresh or dried) is properly cooked and sauced. And then there was gnocchi!— In Genoa I learned to make them delicate and airy rather than the heavy dumplings I had always known. Gnocchi Divino (with a sauce of asparagus and prosciutto) is perhaps the dish I am most often asked to prepare.

My editor encouraged me to emphasize regionalism, something I spoke about often that apparently was seldom part of food writing then as regarded Italy. People may have known regional names such as Tuscany or Sicily and major capitals such as Rome, Naples, Florence, Venice and perhaps Milan. But Bologna was pronounced baloney and Parma was associated with a cheese and maybe a ham, but in inferior versions more likely produced in Wisconsin and Iowa. When I sang the praises of the region of Emilia-Romagna four decades ago, I was often asked “Is that your girlfriend?”

The book I eventually produced contained traditional pasta recipes that could be thought of as genuine or classic because I presented them as I learned them in Italy, making few accommodations for American taste. If an ingredient was hard to secure (such as guanciale—pork cheek) I would propose an alternative that was available. At Carole’s suggestion, the book was divided by geographic regions, an approach that was unusual at the time.

There was Lasagne da Fornel, a baked pasta dish from the Alps with figs, walnuts, sultanas and poppy seeds. Anyone who tasted rigatoni al Gorgonzola from Lombardy could never think of “macaroni and cheese” in the same way again. Farfalle allo zafferano are elegant, simply prepared butterfly shaped pasta with a creamy saffron sauce from Abruzzo.

Some pasta dishes seemed to appear throughout the country in one form or another, but always with local flourishes. For example, spaghetti with delicious Italian tuna has many variations rather than one cardinal recipe. The one I came to love, spaghetti con tonno acciugato, is from the Roman Jewish tradition and is flavored with anchovies, garlic, tomatoes and capers.

As a new author, I was fortunate to have a superb editor with excellent taste and a commitment to creating a book that expressed the ideas and the passion of the person who wrote it. I did not have much say in the title, The Authentic Pasta Book, and never was quite clear whether the pasta was authentic or the book was authentic. In the four decades since it was published, the book has acquired a wonderful reputation as a classic volume that presents pasta the way Italians see it and love it. Historians and journalists often debate what is “authentic” as regards Italian food and there is no simple answer.

I am gratified how The Authentic Pasta Book has come to be seen as a repository of the diversity and ingenious simplicity of the ways Italians use fresh and dried pasta. Is the pasta as presented here authentic? Difficult to say. But what is absolutely authentic is the love and passion about this food that was imparted to me by hundreds of wonderful Italians who became my family. When you make their recipes as found in this book, they become your family too.

About the author

Fred Plotkin is renowned for his expertise on all things Italian, including that nation’s unmatched food and wine heritage. His culinary books combine history, the wisdom of home cooks from throughout Italy, and extensive documentation of traditions that would be lost had he not tracked them down and preserved them in his writing.

Plotkin is also considered one of the world’s experts on opera and has spent his whole life working in that field in Italy, America and elsewhere. He has won numerous awards, culminating in being named a Cavaliere della Stella d’Italia, the Italian equivalent of a knighthood, in 2015.

Top recipes from The Authentic Pasta Book

More ckbk features

Ramona Andrews speaks to some of the many customers now using ckbk to support teaching of culinary arts and food studies

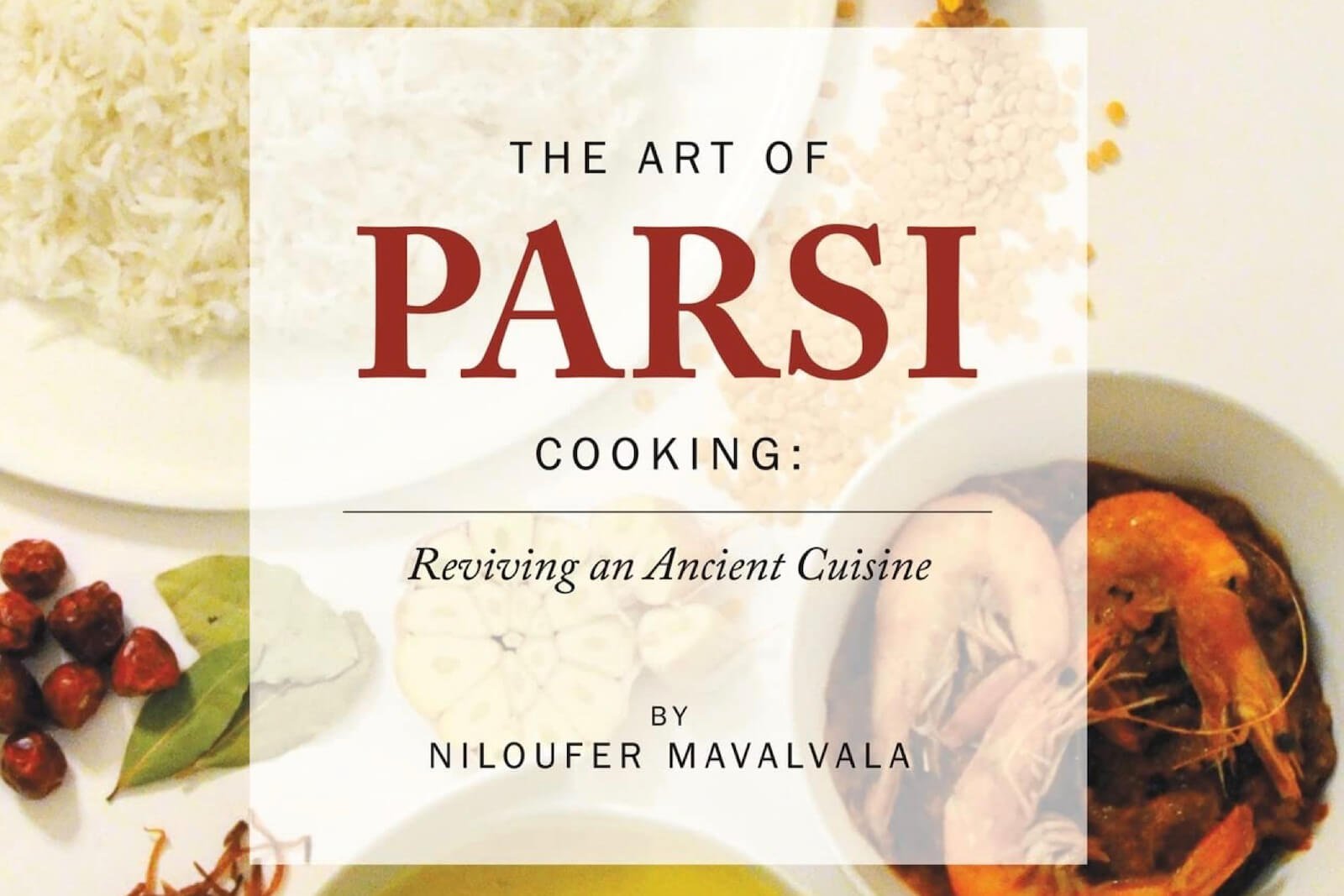

We speak to Niloufer Mavalvala about Parsi cooking, the fusion cuisine which is the subject of her cookbook quartet

Sourdough, bread rolls, rye, pretzels and much, much more. Cat Black offers an overview that will help get you started if you want to dive into dough

Advertisement