Advertisement

How learning to bake changed my life

17 November 2021 · From the Chopping Board

TALES FROM THE CHOPPING BOARD

In this series, ckbk users talk about the cookbooks, authors, and recipes that have influenced them: helping them to finally get the measure of a tricky dish, understand a culinary technique, or build an appreciation of the foods, places, ingredients, cultural history or philosophy of a particular regional cuisine.

This is a space for cooks to share their thoughts on cookbooks and related topics. If you’d like to join the discussion and contribute a piece, drop us a line.

Baker and baking teacher Danielle Ellis tells how the baguettes she devoured on childhood trips to France laid the groundwork for training as a baker in Normandy – and eventually led to her swapping a career in marketing for one as a professional baker and teacher.

Danielle’s recommended bread books will suit bakers of all skill levels.

I am aged 5 or 6 and I am on holiday with my parents in France. We’ve just bought a baguette for lunch and I get to crunch the top off to stave off my hunger.

I am 16 and put-putting on a bike with a tiny motor up a hill in France. I’m working as an au pair, and I am getting the baguettes for lunch (we often went to the bakery three times a day).

I am 21 and there’s a wild, red-haired Scotsman excitedly kneading bread in the kitchen, almost throwing the dough around. It’s Sunday morning and this is his weekly ritual. He’s one of my future husband’s housemates.

It wasn’t until I was in my 20s that I’d considered actually baking bread. For me, bread heaven was biting into the crunchy baguettes that we bought and ate in France. At home, it was bread from the supermarket or occasionally something my mother made, with an odd flavour and the texture of a brick.

Formative loaves

The bread I started making was wholemeal and was always baked in a tin. When my husband and I moved to Bedfordshire we bought our flour direct from the mill, but the recipe never varied.I eventually grew bored with the bread I was making. Time to go on a course, I thought – although not for bread-making, I decided, but for croissants. The class run by Richard Bertinet at his baking school in Bath was a revelation. The way he kneaded flour was so different: it was like being told I had been riding a bike the wrong way the whole time. “You need to get the air into the dough,” he explained, “not squash it out.”

Richard worked hard to make sure that all the students got the kneading technique down to a T. I came away full of excitement. I was hooked. I wanted to learn more. I joined the Real Bread Campaign and saved up bit by bit, and in 2012 I signed up for Richard Bertinet’s five-day bread-making course.

Each of the five days had a different theme. Sourdough would only be taught once we’d first learned all the necessary techniques. We were dedicated to learning, but it was also fun – not least when it was time for coffee, which was served with a prune steeped in alcohol, or lunch at 3pm.

The next step

But what next? I was working in marketing at the time. A bonus from my employer allowed me to buy a stand mixer, but that didn’t sate my desire to learn more. At that time, the only way to learn bread-making professionally was to go on course aimed at young people setting out on a career in hospitality.

I speak French well, so had the idea of going to volunteer for WWOOF (Worldwide Workers on Organic Farms) in France. I’d heard that a local bakery called Boulangerie les Copains, not far from Caen in Normandy, welcomed volunteers under the scheme. Would I have enough stamina to make bread in a professional setting? I signed up for two weeks as part of my annual leave.

The bakery had no electrical bread-making equipment. Kneading was done by hand in huge wooden troughs, using 25kg of organic flour at a time and baked in a wood-burning oven. If I could manage to do this, I would be strong enough to do anything! Apart from electric lighting, this bakery was as it would have been a century ago.

Getting the knack for turning out beautiful sourdough loaves took training

I eventually mastered the technique. The weight of the dough actually helps you. You fold and fold. Different grains needed different approaches, as some were very low in gluten. All was made with levain, no yeast. We shaped, we baked, then we took the bread off to nearby Caen market. I loved selling from the stall. People were buying the bread I had made and I could talk to them about the process.

Le route back to France

Back at home in Edinburgh where I was then living, my marketing job changed. I needed to learn digital marketing, so I set up the Edinburgh Foody blog, and I got to know many of the wonderful chefs, bakers, and producers in Scotland. At the time, a few artisan bakeries were being set up, all small with small numbers of employees. I asked if bakeries would consider me coming to work for them, but none could sustain a trainee.

One day while I was talking to a French-born baker called Katia she said, “Did you realise that until eight years ago I was a scientist? I took a conversion course in France to learn a new trade.” Could I perhaps go to France to learn to bake bread professionally? One of the requirements was to speak French at a sufficiently high level, so I trotted off to the French Institute to be tested. I was indeed fluent enough.

The paperwork was daunting. A doctor had to declare I was fit enough to bake. There were myriad forms to complete. The plan was getting nowhere fast. Then one day Katia excitedly told me that their flour supplier, Banette, was opening up their bread-baking course at L’Ecole Banette, to people from outside France.

To cut a long story short, I was accepted. As the only non-native French speaker it was a challenge at first. The work was intensive and there was a whole new vocabulary to learn. We had a full programme each day of practical (my favourite) and academic subjects (finance, health and safety, theory). By the end of a day, I felt my head was so full it was overflowing. Nothing else would fit in. I then had to do homework!

Most participants taking the course were planning to open a bakery (you have to have a qualification to do so in France). Most of the trainees were men; not only was I not French, but a woman too, which made me unusual.

A baker’s life

It was a life-changing experience. After four months (with a month’s work experience back in Scotland), I had completed 680 hours of training. Back in the UK, I did short work placements with several bakeries, but no job was forthcoming, so I decided to start teaching – at first alongside my marketing work, then after moving to Gloucestershire, as my main occupation.

I now specialise in one-to-one sessions, in person and and online. Some of my students set up a micro-bakeries, while for others it is a hobby. It is so gratifying when people send my pictures of what they’ve created.

I love to discover new bread recipes and have recently been dipping into ckbk. Because of my training, I tend to interpret the recipes, rather than follow them exactly. For example, you might find the author suggests that you have to add sugar and liquid to the yeast to allow it to bubble. This is not needed with instant yeast – you just stir it in! Another bugbear is discarding sourdough starter.

The baker’s bookshelf

For those just starting out, and for those with more baking confidence I recommend three books by Richard Bertinet: Dough, Crust, and Crumb. The recipes are as down to earth and practical as Richard himself. The best book I have found for French breads is The Larousse Book of Bread by the renowned French Baker Éric Kayser. For technical aspects it is hard to beat Jeffrey Hamelman’s sturdy book Bread – you definitely need experience to get the most out of this one!

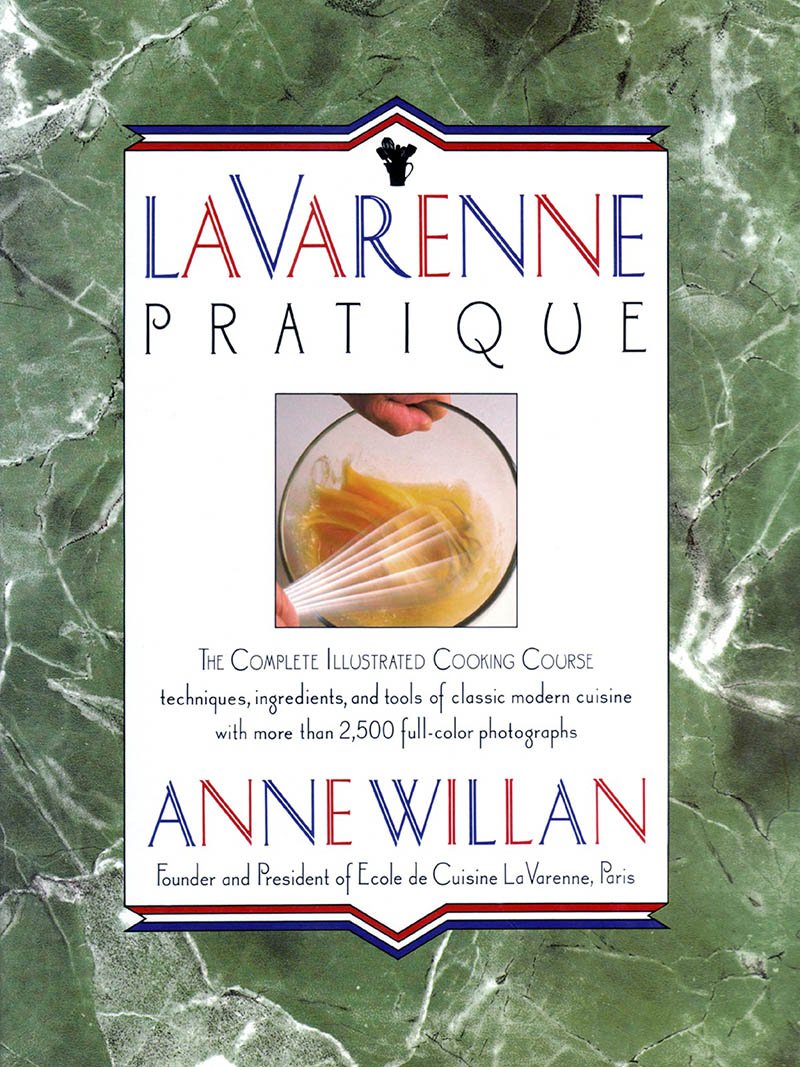

Being a member of the Real Bread Campaign is important to me. Slow Dough, Real Bread, written by the Campaign’s coordinator Chris Young, features recipes sourced from artisan bakers, with a wonderful choice of ingredients and heritage flours. Other standouts include: Bourke Street Bakery, Bien Cuit and La Varenne Pratique, all of which use straightforward techniques and have great recipes.

Happy reading, and happy baking!

You can find Danielle at Severn Bites severnbites.com and @breadbakerdani on Twitter and Instagram.

Would you like to contribute a post to the new Tales from the Chopping Board section? Get in touch!

More posts from ckbk

Advertisement