Advertisement

Behind the Cookbook: Rux Martin on Classic Home Desserts

16 April 2020 · Behind the Cookbook

The Making of a Classic

by Rux Martin

More than any other author I’ve ever worked with, Richard Sax appreciated the power of desserts to soothe and fortify in dark times. He understood that when things are going well, we may brag about our high-protein diets and the latest bean dish we’ve discovered, but in the face of an apocalypse, the urge to bake is primal. And when it came to fighting an invisible international killer, Richard knew a thing or two about that, too.

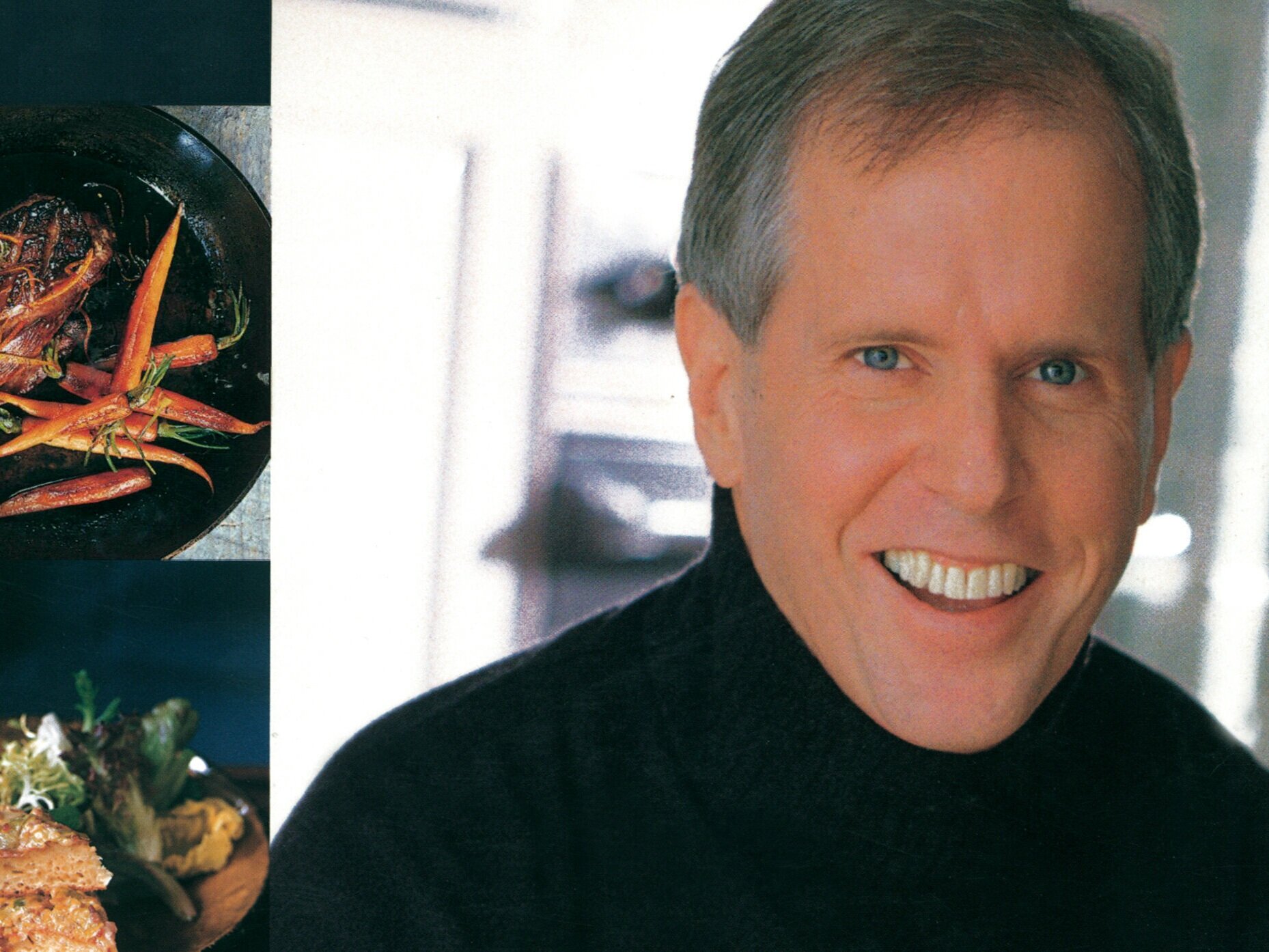

When I began working with him on Classic Home Desserts in 1993, he was at the height of his talents as one of the best-known food writers in America. He had been the former director of the test kitchen at Food & Wine, where he excelled at turning chef creations into dishes easily made at home. He was a teacher par excellence. It was the golden age of magazines, and Richard was one of its princes. He co-wrote a monthly column on home cooking for Bon Appétit, and he turned out book reviews, restaurant reviews, and cooking pieces for a wealth of other publications: Gourmet, Yankee, Harper’s Bazaar, the New York Times, and Out, to name just a few. Though Richard could and did cook everything, it was in the realm of desserts that he shone most luminously.

In the 1980s, he had published a slim paperback on home desserts. Realizing that he’d barely scratched the surface of what the world had to offer, he spent the next ten years searching out the best sweets he could get his hands on. Although his reach was encyclopedic — he scooped up everything from a yeasted German coffee cake of an Alsace bakery to the custard pie of an Iowa mom to an apple crumble recipe published in 1744 — his focus was laser-like. To be considered for his book, each dessert had to be tops in its category, whether it was an unassuming American icebox cake or a crisp Austrian poppyseed strudel. He had one more crucial criterion. Each dessert must have, as he put it, “a spirit of unadorned frankness.” Richard was unimpressed by the formulations of high-hatted pastry chefs. Instead, he was drawn to the homey recipes of mothers, grandmothers, and other humble cooks — or those of chefs who cooked like them— recipes that had proved themselves around family tables for generations. He had unerring radar for the best. Testing and perfecting them, he created a gargantuan work of more than 350 recipes, each one a gem.

The major New York publishers that Richard’s literary agent approached loved the book, but citing the cost of printing a full-color book of hundreds of pages, all of them insisted that he chop it to a mere 150 recipes. Richard had no intention of diminishing his magnum opus, so he told his agent to keep trying. At Chapters, the tiny Vermont publisher where I worked at the time, we jumped at the chance to publish what we believed would be one of the most important books on dessert ever written.

Alone in my office, I stared at the manuscript, a more than three-foot-high stack that stretched halfway up my thigh. It was a towering work — literally. In addition to the desserts themselves, Richard had assembled hundreds of pages of snippets about desserts from every conceivable source: an obscure 1600 play, a Walt Whitman poem, a New Yorker cartoon caption, TV-commercial nuggets. He’d mined unforgettable descriptions from seemingly every literary work whose author had ever mentioned a dessert. Many of the quotes stretched on for pages.

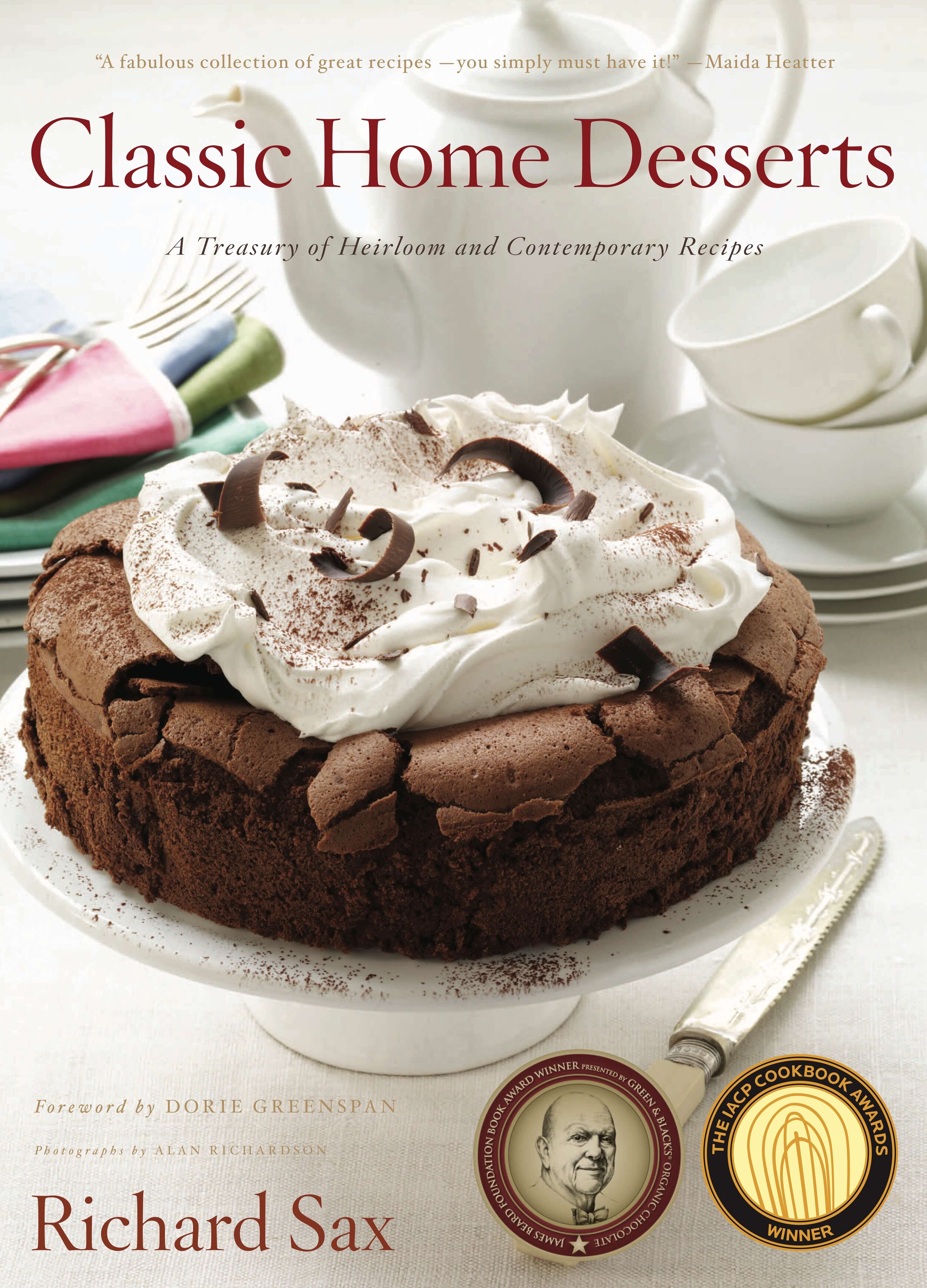

And the desserts! A spectacular, perfectly classic pumpkin pie that Thanksgiving was made to celebrate, with a delicate, yet complex spicing that keeps the taste of pumpkin in the foreground. Chocolate Cloud Cake, “a flourless extravaganza,” Richard called it, so airy, yet sumptuous that your taste buds float in it. A bread pudding with a potent whisky sauce—you practically need a liquor license to serve it. A classic biscuit strawberry shortcake, a purist’s dream. A silky crème brûlée with a crackling top that tells you why the dessert became a sensation.

But as for turning that giant manuscript into a book, I was definitely not up to the job. I had edited only a handful of titles before, mostly books that had gone out of print that I had lightly retouched before reissuing them. I’d never done a dessert book. In fact, my baking skills were so pathetic that my own family had once begged me not to make Christmas cookies. Be careful what you wish for, I thought, as I contemplated the stack, my heart thudding in my chest.

We had fewer than ten months to come up with a title and subtitle, put the desserts into roughly equal chapters, apply a consistent style to recipes that had been written over the course of a decade, decide which should be photographed and have them shot, get the thing copyedited — I figured that would require at least a couple months — design the book, and proofread it. The index would take weeks. Printing it would take the better part of a month. There was nothing to do but begin.

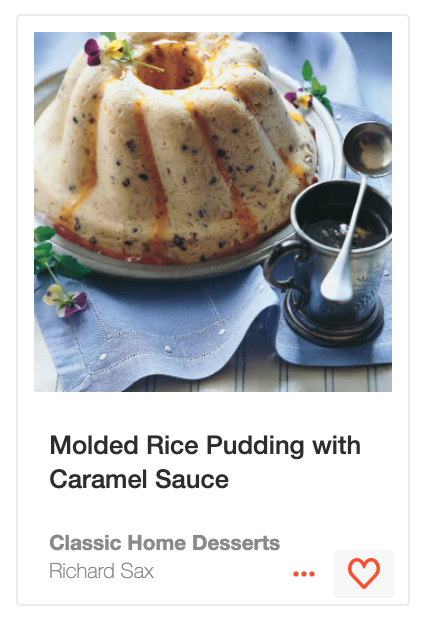

Our first task was to decide which recipes should be omitted: the book was way too long. Richard had collected more than thirty noodle puddings and kugels alone. I recommended cutting all but one. But Richard believed that they, along with the bread and rice puddings (of which he had also had dozens), were foundational, not just to Jewish and Eastern European cuisine, but to the whole world of old-fashioned desserts. We finally agreed on three.

Some desserts seemed to defy categorization. Where to put the pumpkin pies? I thought they belonged with the fruit pies, (admittedly I was stretching the definition of fruit), since they clearly didn’t fit with nut pies, ice cream pies, or mincemeat pies. Nick Malgieri, the noted pastry chef, and a close friend of Richard’s, gave us a short course in taxonomy, explaining that, being custards, they belonged with the other cream pies.

I cut the hundreds of pages of literary quotes into manageable bites that could be placed in the margins, saving space and providing a dialogue between the past and present. Alan Richardson captured the soulful beauty of the desserts with his photographs, and the designer created a space-saving but very readable and practical design. Richard and I continued to work frantically, well into the early hours of the morning. As I edited and he revised and answered questions, we overnighted the chapters dense with scribbling (this was long before the days of email and electronic editing) back and forth between New York City, where Richard lived, and Vermont. We were making progress, but we still had miles to go.

During extended phone calls, we laughed, gossiped about the food world — Richard was pals with everyone, people who were only famous names to me —and bickered. We became friends. Richard was the kind of man you could confide in. He was the life of any gathering, with large, lustrous eyes, glossy black hair, an ebullient smile, his clothes classically elegant. At least twenty years before social media, he was a super connector, a key influencer, and an activist for the hungry, the homeless, and for the gay community. Through Richard, I met — or heard about — many of the major authors I would publish many years later.

Then, rather suddenly, Richard began to fall behind in his work on the book. For the first time, there were days I couldn’t reach him. The chapters didn’t return on schedule. He was in and out of the hospital. He lost weight. He fretted about his appearance, a bruise that had appeared on his face. Regarding what was wrong, he was mysterious, and he warned me to tell no one he was sick. But though we never spoke about it explicitly, the community of Richard’s close friends did know. It was the height of the AIDS epidemic, and thousands of beautiful and talented men like Richard were dying. There was no cure.

The head of our cash-strapped company nervously asked for regular updates on the book, which was a major investment. I assured him everything was fine. Meanwhile, in my head, I spun disaster scenarios: Richard would not be able to finish the book, Richard would not live to see the publication of his life’s work, our company would be bankrupt and unable to publish the book, and on and on.

With the editing finally finished, we somehow made it through the interminable process of copyediting, under the smart guidance of Mardee Haidin Regan. Sick as he was, Richard painstakingly answered all her questions and reviewed the manuscript again. The process of laying out the book began. Because books can’t be just any length — they must be multiples of sixteen or thirty-two pages, called “signatures” — more cutting was necessary to make it fit into the 688 pages we had allotted. Richard and I conferenced over the phone and agonized over which recipes we could lose. I sent the cuts to the designer. When she finished, I realized we’d cut a recipe that had been photographed. Worse, it fell at the front of the book and restoring it would throw off the pagination of the rest. The designer had to redo almost the entire book. But as I laid out the newly completed pages, I saw with horror that I had scrapped yet another recipe that had been photographed. I threw myself down on the floor and, in full sight of the staff, bawled like a baby. The designer began again.

Then, unbelievably, the book was finished. Support from the cookbook world’s greats — Marion Cunningham, Maida Heatter, MFK Fisher, and more flooded in. The following spring after its publication in 1994, Classic Home Desserts won both a James Beard and a Julia Child Award (now called the IACP Award, for the International Association of Culinary Professionals) for the best dessert and baking book.

In September 1995, a few months after the award ceremonies, Richard died, having fought AIDS with almost literally his last breath. He was forty-six.

Richard’s masterpiece remains as timeless as ever. It’s the book I go to most often during the holidays and for every other occasion when I want something effortlessly perfect. Recently, a friend told me that she has baked a different chocolate cake for her boyfriend’s birthday every year: a chocolate cake with brown sugar buttercream, a devil’s food cake with coconut buttercream icing, then a chocolate buttermilk birthday cake, all from the books of leading baking authors. This year, she made the Fudgy Chocolate Layer Cake from Classic Home Desserts. It was the best of all, she reported.

Richard’s chocolate cake is not tricked out with frou-frou ingredients. It doesn’t call for fancy chocolate — not a pricey brand, not 70 percent dark, not even bittersweet or semisweet. Just ordinary cocoa powder, with unsweetened chocolate for the frosting. It is, he wrote, “a down-home, all-American chocolate cake. . . chocolatey without veering into the realm of fudge or brownie.” All Richard’s recipes are that way: they taste like something your mom would have made for you if she were the best cook in the world. They are simple goodness.

Nearly twenty-five years after Richard’s death, as we find ourselves sequestered from an invisible plague, his recipes beckon.

Rux Martin is an independent editor specializing in cookbooks. She was editorial director of her own imprint at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Her authors have included Jacques Pépin, Dorie Greenspan, Michael Solomonov and Steven Cook, Antoni Porowski, Pati Jinich, Maangchi, Ivan Orkin, Molly Katzen, Marcus Samuelsson, Ruth Reichl (The Gourmet Cookbook), and Judith Jones (Knead It, Punch It, Bake It!). Many of the books she edited reached the New York Times bestseller list, including Antoni in the Kitchen, Hello, Cupcake!, Around My French Table, and Zahav. She lives in Vermont, where her office adjoins a chicken coop.

Classic Home Desserts is a featured book on ckbk, home to the world's best cookbooks and recipes for all cooks and every appetite. Start exploring now ▸

Related Posts

Sign up for ckbk's weekly email newsletter

As an added bonus you will receive a free PDF download featuring recipe highlights from our favorite cookbooksAdvertisement