Advertisement

Q&A with Iraqi food expert Nawal Nasrallah

10 May 2022 · Author Profile

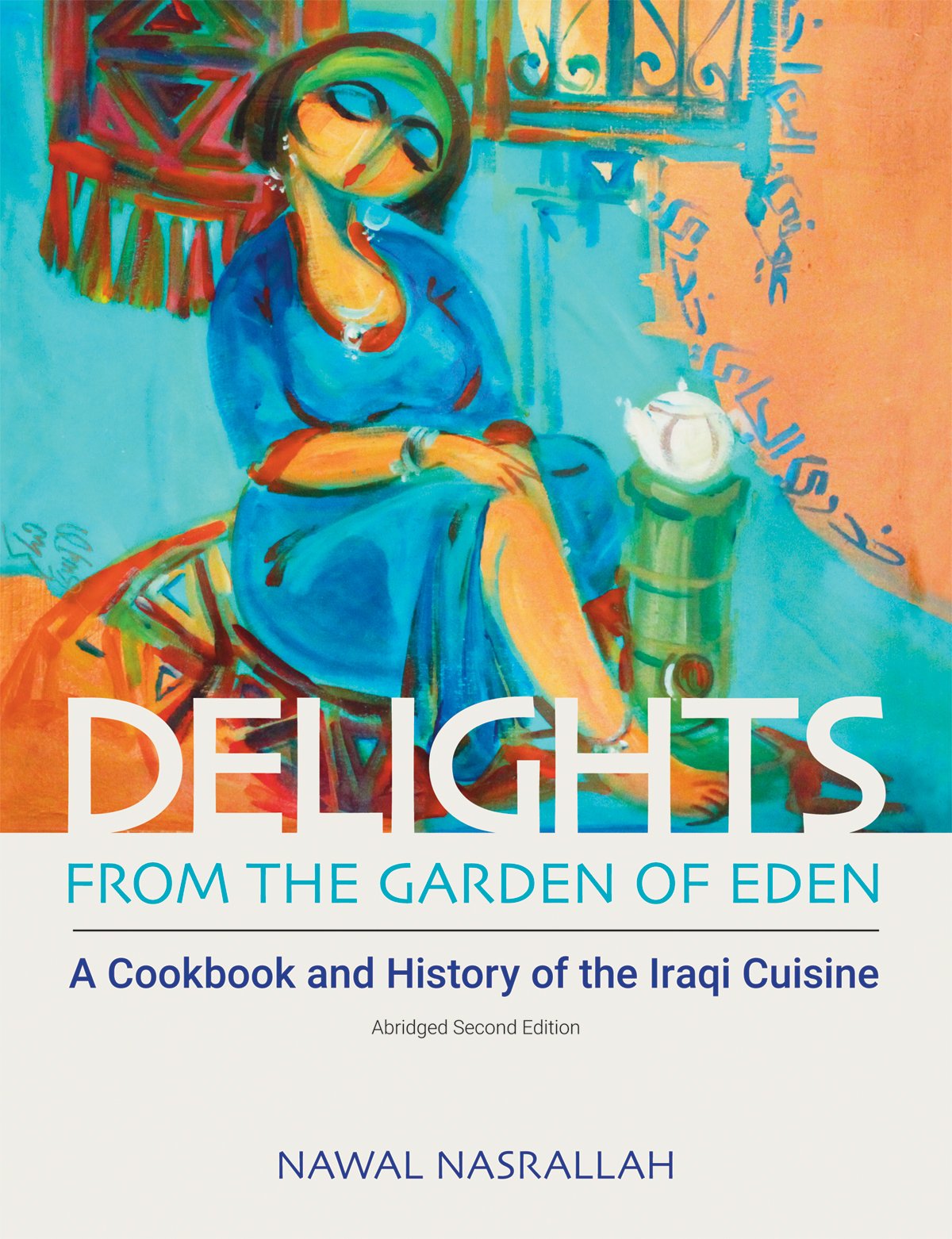

We speak the author and translator about her book Delights from the Garden of Eden: A Cookbook and a History of the Iraqi Cuisine

Nawal Nasrallah is an expert on medieval Arab cuisine, and on modern Iraqi cuisine.

Nawal Nasrallah was born in Baghdad and now makes her home in New Hampshire in the northeastern US. A food writer, food historian, and an English-language scholar, she is also a translator from Arabic to English. She is an expert on medieval Arab cuisine, and on modern Iraqi cuisine and its antecedents, including the food of ancient Mesopotamia.

Her authoritative guide to Iraqi cuisine, Delights from the Garden of Eden: A Cookbook and a History of the Iraqi Cuisine, is now available in full on ckbk. It was first published in 2003, the same year in which the US invaded Iraq, and steadily built a loyal following.

In 2007 the book received the Gourmand World Cookbook Special Jury Award and in 2013 Saveur magazine chose that year’s edition of the book as one of its top ten food books of that year. The revised and updated 2019 edition, published by Equinox, contains tried-and-tested recipes, with food photographs and striking illustrations providing cultural context.

Q: Delights from the Garden of Eden was originally self-published in 2003. To what extent have attitudes changed? Are people (and book publishers) now more open to less-familiar cuisines and tastes?

It is a different world now. More and more readers are curious about cuisines of regions they are not so familiar with, and such books are indeed in demand, especially the well-packaged ones with good text and decent production. Publishers also seem to be more adventurous in accepting such manuscripts.

Q: Which ingredients would you recommend that cooks new to Iraqi food buy and keep in their pantry?

Make sure you keep some dried limes in it. We call them noomi Basra because they were originally transported to Iraq from Oman through the port city of Basra. Also to be kept is the spice mix baharat.

Q: Which spices, ingredients, or techniques make Iraqi cuisine stand apart from its neighbors?

Tough question. The way I see it is that Iraq shares most of the ingredients with the neighboring regions, simply because we share a more or less similar climate and topography. What sets the regions apart, including Iraq, is how the ingredients are actually used. It is here that we can talk about distinctive features between the Levant, for instance, and Iraq.

A simple example may be bulgur, available in both regions: nobody makes bulgur kubba, especially the huge flat discs, the way Iraqis do. While we all make dolma, in Iraq it is always a festive dish made with an enticing assortment of vegetables.

Having said that, only Iraqis use a variety of mint called butnij, which is river mint. It is always difficult to find it outside Iraq. I get my stash online – I managed to get the authentic butnij after many failing attempts, when I would be sent just regular mint. It is exclusively used in a fava bean dish called tashreeb/thareed bagilla.

I can say the same thing of a spicy condiment called amba, which is pickled mango. It is closely associated with Iraqis, and the people who have spread it far and wide are the Iraqi Jews who had to leave the country during the 1941 pogrom, Farhud. Those who went to Israel spread the word about amba, especially through their restaurants and sandwich food stalls.

Q: Are there any cooking techniques that are distinctively, uniquely Iraqi?

I would say Iraqi cooks are proficient in the art of stuffing and rolling foods, such as the myriad varieties of kubba dishes using bulgur, rice, and potatoes.

A fish dish that is not usually cooked at home but purchased from fishermen along the river Tigris is masgouf. Fishes impaled on sticks are slowly grilled around a camp-like fire. The smoky flavor of the fish is unforgettable.

Q: You will be in London for the British Library Food Season, discussing the world of 13th-century Moorish food with chefs Samuel Clark and Samantha Clark on Saturday, May 21. You were the translator of that manuscript, which was eventually published as Best of Delectable Foods and Dishes from al-Andalus and al-Maghrib. How did that come about?

My knowledge of the medieval Arabic cookbooks, including this one, goes back to the time when I was writing Delights from the Garden of Eden, for my research on the medieval era. That was an eye-opening experience from me. After I was done with the Iraqi cookbook, I took it upon myself to translate into English those wonderful medieval cookbooks. It is an excruciating process, slow, and requires a lot of probing into other contemporaneous sources, such as books on botany, farming, dietetics, literature, and the like. I cannot complain, really, for it has been an enjoyable experience for me – stimulating, challenging but also rewarding. I first worked on the Baghdadi one from the 10th century (Annals of the Caliphs’ Kitchens), then the 14th-century Egyptian one (Treasure Trove of Benefits and Variety at the Table), and the 13th-century Andalusi-Maghribi cookbook (Best of Delectable Foods and Dishes).

Q: What was the most exciting discovery from that translation or process?

The experience was indeed an exciting one. I came to know the real text itself. By consulting the three manuscripts available to us, and not being restricted to the Arabic printed edition of the work, I discovered many of the original scribes’ misreadings, which I was able to correct. I also learned how ingredients that we are familiar with nowadays were cooked many centuries ago in more complex and interesting ways than we do today; but also how some of the cooking techniques have endured and persisted.

Q: Do you own or read a lot of cookbooks? Do you have any favorite authors or books?

Oh, yes! Lots of them. I love books that tell me about the cuisine, its history, its culture, etc. Paula Wolfert, my favorite, is so meticulous in discussing Moroccan cuisine; her enthusiasm is contagious. Clifford A. Wright’s A Mediterranean Feast is a phenomenally vast and thorough coverage of the region. There are many other good ones, but these two always stand out for me as excellent examples.

Q: Do you consider cookbooks to be ‘important’ in any way? If so, how?

Certainly, in many ways. The most obvious thing is to learn to cook new dishes, or even learn to cook well the ones we already know, or think we know. Through reading them we also get to learn a good deal about others: their culture, modes of life, customs, history, and the like. To me, cooking is the best way to introduce readers to a region they are not familiar with.

Q: Which recipes from your book hold the most meaning for you, and why?

I would choose the Iraqi flatbread we call khubz il-tannour, which is traditionally baked in a domed clay oven (tannour). It is simplicity itself, made of flour, water, salt, and yeast, and yet it yields the most delicious bread, so familiar and yet so indispensable. When I left home, I missed it terribly; it took me a long while to make it taste and smell like home.

There is also our kleicha, which we consider our national cookies. Although we make them year-round, they are specifically in demand for the feasts, be they Muslim ones, Christian, or Jewish. Families make them in large amounts and store them in wicker baskets covered a cloth, so that they last at least for a week, to be eaten by the household and guests alike.

Old and young members of the family were expected to pitch in making them. Some are stuffed with nuts, some with dates, and yet others are left plain. The entire house would be redolent with the aromas of cardamom, cinnamon, nigella seeds, aniseeds, and rosewater. They always remind me of the fun times I had.

Popular recipes from Delights from the Garden of Eden

Your chance to see author Nawal Nasrallah in person

As part of the 2022 British Library Food Season, Nawal Nasrallah will take part in a panel discussion on The World of 13th-Century Moorish Food on Saturday, May 21. The panel, chaired by podcaster Gilly Smith, will focus on a recently discovered manuscript cookbook by 13th-century Andalusi Scholar Ibn Razīn al-Tujībī. Nawal Nasrallah’s English translation of this manuscript was published in 2021 as Best of Delectable Foods and Dishes from al-Andalus and al-Maghrib.

During the talk, Samuel Clark and Samantha Clark (founders of famed London restaurant Moro, and authors of The Moro Cookbook) will create dishes inspired by the manuscript and discuss the history and culture of the region with Nawal and British Library manuscript curator Bink Hallum.

Sign up for ckbk's weekly email newsletter

More features from ckbk

Q&A with Sharon Wee

Sharon talks to ckbk about her influential cbook, Growing Up in a Nonya Kitchen.

Advertisement