Advertisement

Q&A: Annabel Abbs on Eliza Acton

2 February 2022 · Author Profile

“I want to put Eliza back on the stage where I think she belongs”

Annabel Abbs: bringing Victorian cookery writer Eliza Acton into the 21st century and to a wider audience.

Photograph: Guillemette Minisclou

By Susan Low

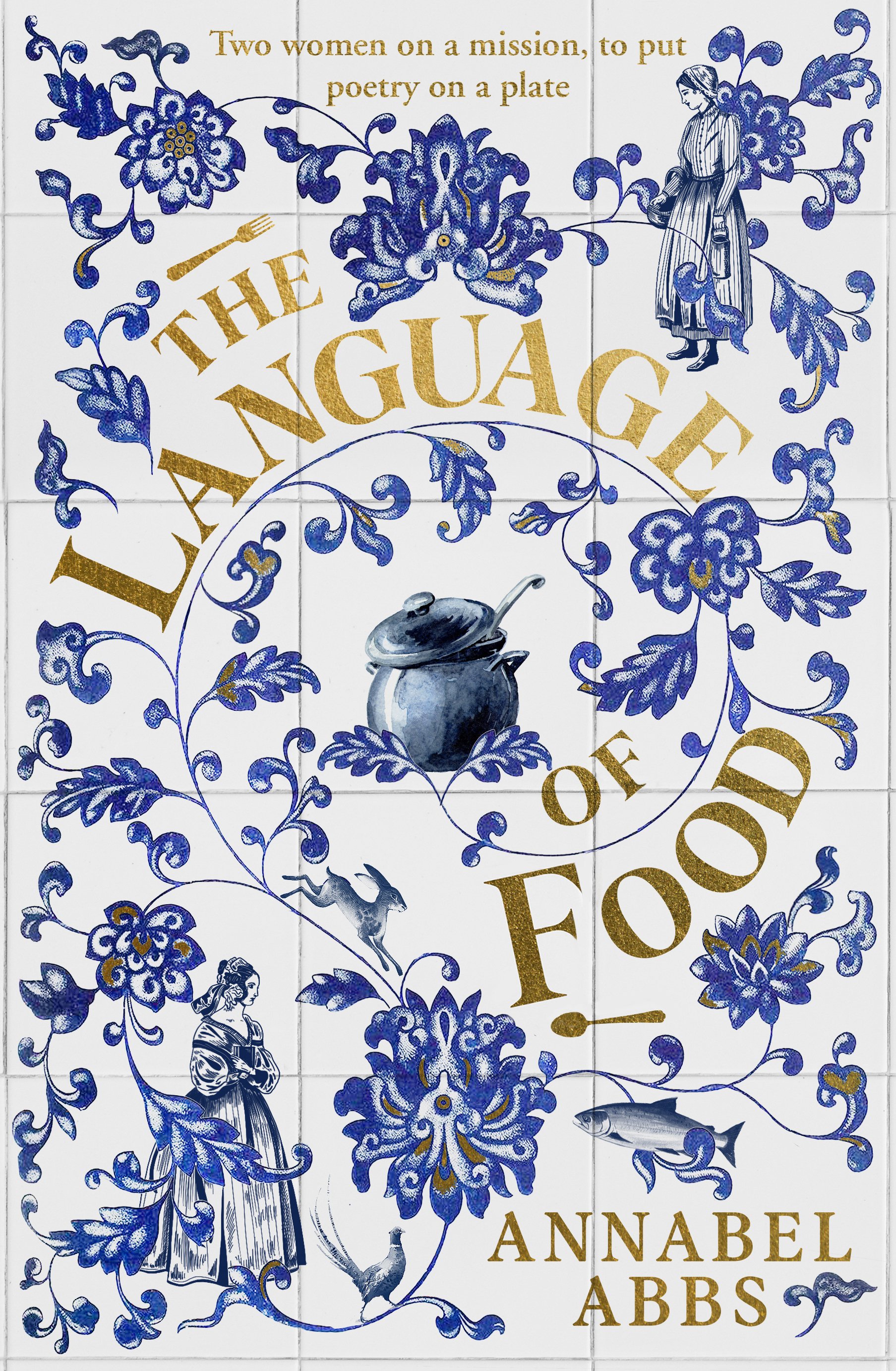

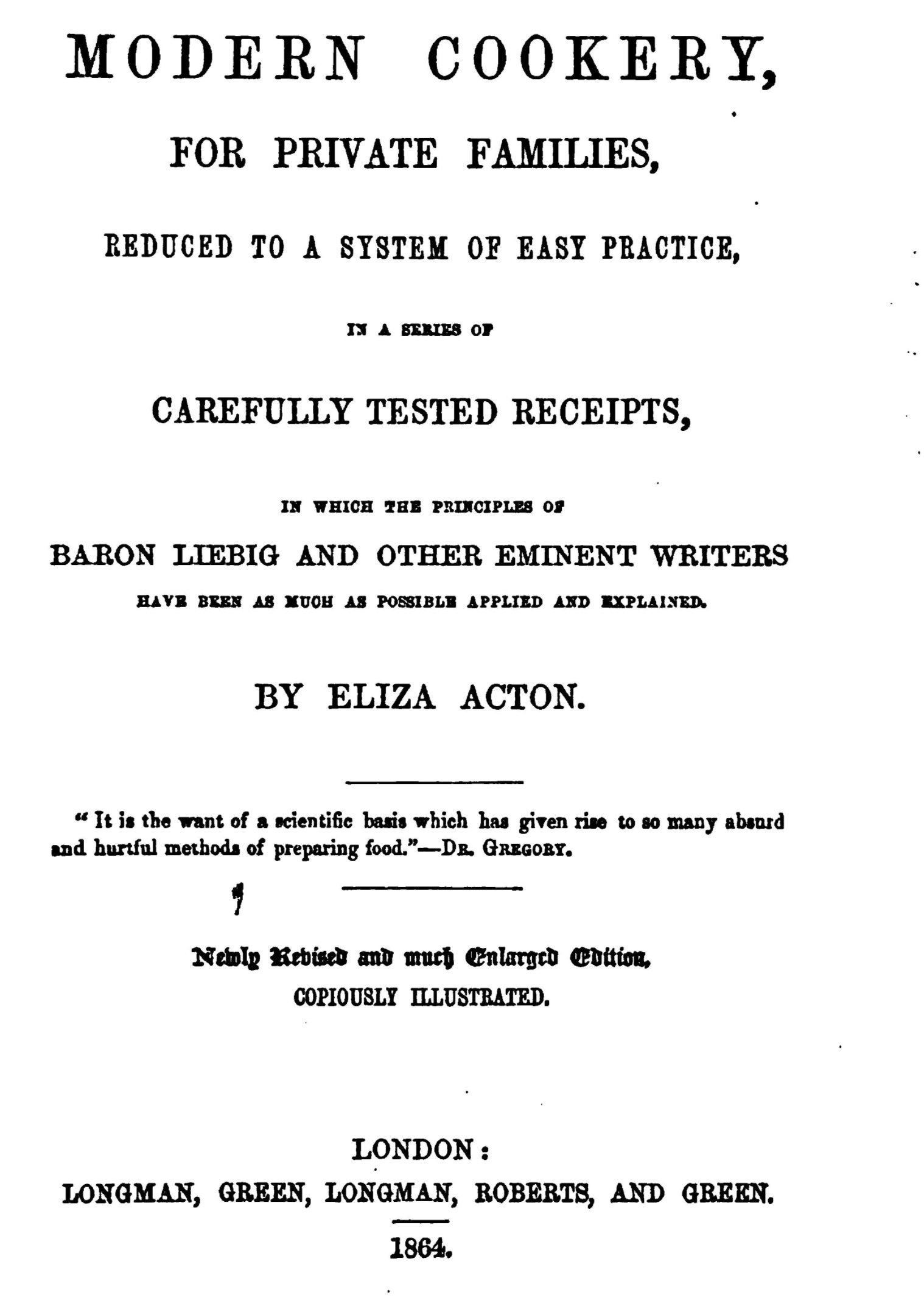

British author Annabel Abbs is a leading writer of biographical historical fiction. Her third novel, published as Miss Eliza’s English Kitchen in the US and The Language of Food in the UK (out on February 3) tells the story of Eliza Acton, who wrote the ground-breaking Victorian cookbook Modern Cookery for Private Families, published in 1845 and available in full on ckbk.

Abbs’s novel explores the creativity and joy of cooking and aims to bring Acton out of the archives and back into the public eye. The book is being made into a television miniseries by CBS in the US by Stampede Ventures, which will give Acton and her work some well-deserved limelight.

Eliza Acton’s name may not be as widely known as some of her rivals, such as Mrs Beeton, but in the food writing world she has real cachet. Acton’s admirers include Delia Smith, who called Acton “the best writer of recipes in the English language,” Elizabeth David, who wrote the introduction to The Best of Eliza Acton: Recipes from her classic Modern Cookery for Private Families, published in 1968, and Jane Grigson, who has paid tribute to Acton in her own cookbooks. Food writers such as Dr Annie Gray, Regula Ysewijn, and Frances Bissell have also paid tribute to Acton with their contemporary takes on Acton’s recipes.

Acton’s Modern Cookery for Private Families changed the rules on what and who cookery books were for. It was the first to be written for amateur home cooks rather than professional chefs and Mrs Patmore types: Acton dedicated the book to ‘the Young Housekeepers of England.’ Acton was the first to list ingredients and the amounts needed separately from the body of the recipe – although she listed them at the end rather than the beginning – and she was the first to give accurate cooking times and temperatures.

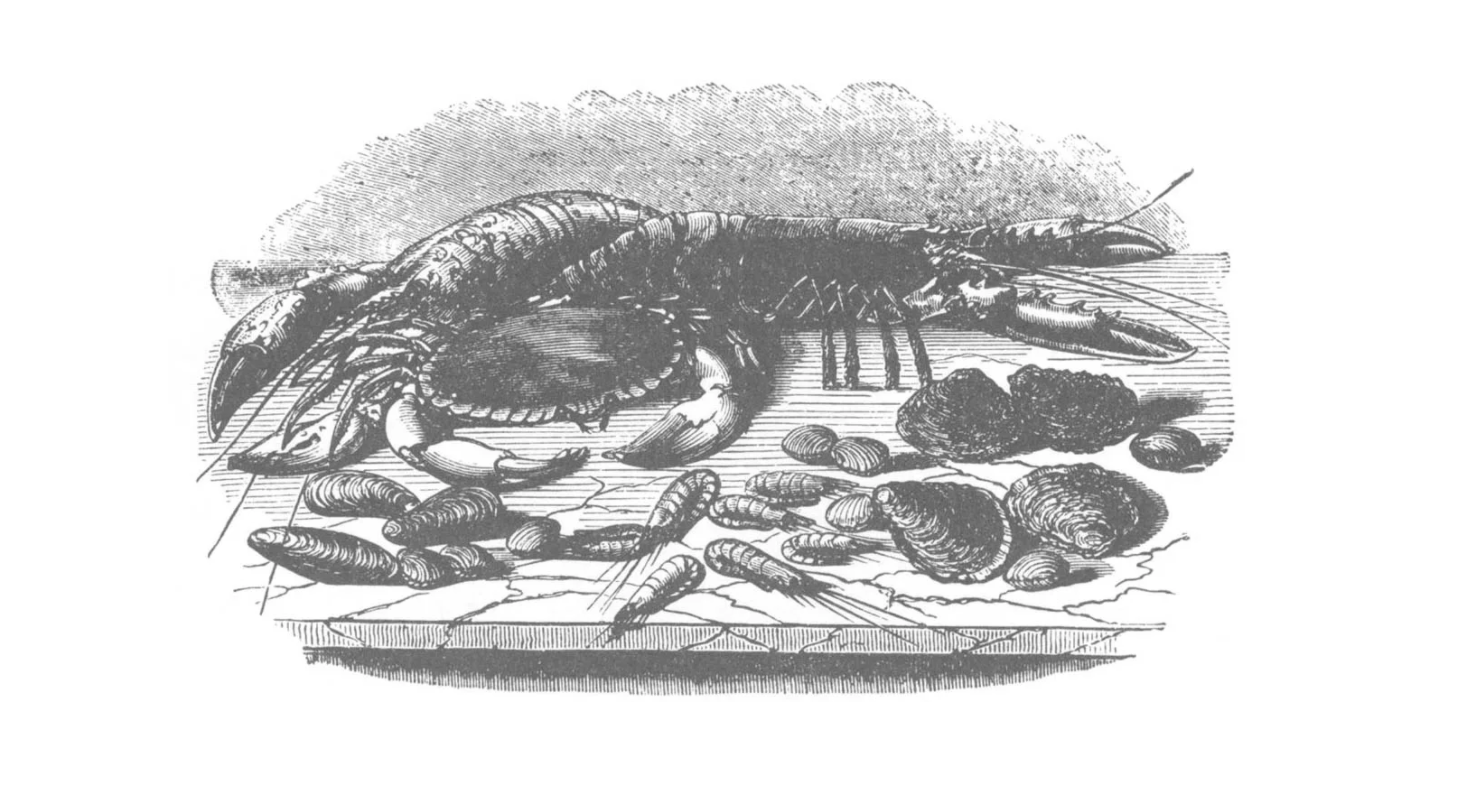

Long before the days of full-colour food photography, Acton used simple but accurate line drawings to give readers an idea of how to identify shellfish or how to spot a sirloin of beef at the butchers. In common with many modern food writers, Acton loathed food waste. In the preface to Modern Cookery, she bemoans “the daily waste of excellent provisions,” which “almost exceeds belief,” and argues for procuring good, wholesome food (food adulteration at the time she was writing was rife).

Acton was a stickler for accuracy, testing her recipes until they could be successfully replicated. A published poet, she combined a scientist’s precision with the literary nous of a skilled wordsmith. Modern Cookery could be read for pleasure as well as purpose.

Together, these innovations have resulted in Acton being called ‘the first modern cookery writer.’ Is that a fair description? Jill Norman, who wrote the introduction to the 2011 edition of Modern Cookery published in the UK by Quadrille, believes it is. “I would certainly agree that Acton was the first modern cookery writer,” she says. “Her writing is clear and concise (but so are others). The significant development was that she was the first to introduce a list of ingredients and cooking times at the end of each recipe. This alone was a great step forward. Her clarity and precision are important, too. Her approach was adopted by later writers and continues in most books today.”

Dr Annie Gray is a bit more circumspect. “I wouldn't wholeheartedly agree,” she says. “There’s this constant search for the first modern cookery writer – what does that even mean? To the extent that Acton’s recipes are very easy to follow, and that she was one of the very first authors to list ingredients separately, she is ‘modern.’ But I suspect most people today would still struggle to follow her instructions, and other writers from the time also write very clearly (Maria Rundell, for example).”

Gray is, nevertheless, a huge Acton fan. “If you cook from her, you’ll find marvels,” she says. “Not just recipes, but also really good advice (yes, mushrooms do improve every suet pudding, and yes, cakes often are just sweet poison). Frankly, Modern Cookery is worth having for the Cucumber Soup, Nesselrode Cream and Fashionable Apple Dumplings alone. And the pie: I learned to cook pie from Eliza Acton. Her pies rock.”

Annie Gray’s recipe from How to Cook the Victorian Way with Mrs Crocombe, adapted from Eliza Acton’s Nesselrode Cream published in Modern Cookery.

Modern Cookery was an immediate and long-standing success, running to 13 editions and earning Acton a tidy sum in the process. Despite the book’s success, Acton’s place in history was soon supplanted by another Victorian queen of the kitchen – Mrs Isabella Beeton. Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management eclipsed Acton’s when it was published in 1861 – which was exceptionally galling for Acton, as Beeton is known to have used many of Acton’s recipes in her own book without crediting them (plagiarism in the food-writing world is nothing new). Perhaps even more galling is that, outside the food-writing cognoscenti at least, Mrs Beeton’s name is now better known than Eliza Acton’s.

If Annabel Abbs has her way, of course, all of that will change and Eliza Acton will be recognised for her many achievements.

We spoke to Annabel about how she came to know Eliza Acton’s work and why she believes Acton deserves to be better known. Here’s what Annabel had to say…

Q How did you first come across Eliza Acton?

I inherited a cookery book collection, which I still have, from my mother-in-law. She was a cookery teacher in the 1950s, and she worked on Good Housekeeping magazine as well. Way before it was fashionable, she started collecting cookery books, and had a collection of about 200 historic books. When she decided she didn’t want them any more I inherited them. I had small children at the time and one day my 4-year-old had scribbled all over this priceless 17th century book – so I locked them away in a cupboard and didn’t look at them for 15 years.

When I was looking around for something to write about – I wanted to write about a female who had not been recognised – I started going through all the cookery books, and her book just stood out. Her prose is so good. I didn’t know much about her but when I started to research her, she sounded interesting and had a good backstory – there was the whole thing with Mrs Beeton stealing her recipes! Her recipes were plundered by many people, according to [Eliza’s] introductions. In a later edition of Modern Cookery, she talks about how all the plundering and the plagiarism had made her ill.

I started cooking from her recipes and I really liked them. All the time I was writing the novel, once a week I’d cook something from her book and often it was surprisingly delicious – although occasionally it didn’t work, and it took me ages to realise that the measurements are different.

She’s always spoken to me through her recipes, and I liked unearthing her culinary history. English food of the time is disparaged, and seen as unhealthy and full of lard, but actually it’s not. She was doing a lot of stewing and gentle simmering, lots of soups and casseroles, and there’s a French influence and an Italian influence.

Q What it was about her that captured your attention?

I loved her creativity. Cooks are often at one end of a spectrum – either very carefully working out the chemistry of it, and the weights and measurements are all very important; at the other end, they’re more slapdash and think about what flavour might work with what. But she seemed to do both. I liked the way that she brought her creativity into her beautiful prose – which has a touch, to me, of someone like Nigella Lawson or Nigel Slater. It’s beautifully written, but then she also has this precision.

For me, that’s because she had worked within the format of poetry. Poetry is so tight, it’s so ordered, and the structure is important – and she seemed to bring that to her cooking. She’s a bit like Delia in that respect. She really wanted to be able to show people how to cook in their own kitchens, with the ingredients that they had to hand.

Q Why did you decide to write this book?

Partly because I really love reading about food. Food is such a great thing to write about, and to explore the place of food and its ability to cross so many boundaries. Obviously, in The Language of Food, I’m looking at class and how it manages to cross that boundary. I wanted to look at the joy of food, and how it can cement relationships and nurture relationships – how cooking can make people happy.

I would love to see everyone cooking more and relying less on fast food. I think that one of the reasons Eliza loved writing Modern Cookery was because she wanted to share her pleasure in cooking, and stop people having pies in the street which, at the time, were full of so many awful things. All that adulterated flour and adulterated tea. Just like now, the less money you had, the worse the fast food was. I also wanted to put her back on the stage where I think she belongs. It seems to me that all the foodie and chef community know of her, but most ordinary people don’t know who Eliza Acton is. They might know who Mrs Beeton is, but they have no idea who Eliza Acton is, and I don’t feel that’s right. I think she needs to be put back. She’s probably the first real modern food writer.

Q Why is she worth remembering and why do you think she matters in the world of food-writing?

For her pioneering role in food-writing, for her beautiful prose – she really is the first one to bring poetry to her recipe-writing – and for the invention of the recipe. She is the first person to list the ingredients and the measurements separately from the method. She puts them at the end of the recipe – and all fairness to Isabella Beeton: she recognises that actually a better place would be to have them at the beginning! And that is her innovation.

Nonetheless, the real innovation was Eliza Acton’s – pulling them out and listing them and with precise measurements. Previous food writers were cooks and housekeepers in big homes – they were writing for other cooks, so they didn’t need to spell it out. But Eliza hadn’t cooked, so as she’s teaching herself, she realises that she needs to pass that on to her readers. She is the inventor of the recipe of today.

Q Which of Eliza’s recipes would you most recommend?

Quite a few. Some of them are very surprising. Have you ever made Delia’s marmalade bread and butter pudding? I think she got the idea for that from Eliza’s Good Daughter’s Mincemeat Pudding. In this one, Eliza uses old bread buttered, she puts layers of mincemeat, and she makes a custard.

Other things: some of her simple things are really good: her Prunes in Red Wine are absolutely delicious. My 23-year-old daughter is absolutely obsessed with them. She does an Apple and Ginger Soup and that is really, really delicious.

Her Soup in Haste is really nice; it’s diced vegetables and bits of meat and you just simmer it. You can cook it in half an hour so a busy housekeeper or a busy mum could stick the ingredients in a cooking pot and put it over the fire and have something to eat in half an hour.

Her Pound Cake. Her cakes are good, old-fashioned English cakes that you could have a big slab of. They’re full of raisins and sultanas and things. And her Jewish Almond Pudding, which I write about in The Language of Food.

Q And you have a mission, don’t you, to restore Eliza Acton’s unkempt grave at Hampstead Parish Church in north London. Tell me more…

I went to try to find her grave – it’s so overgrown you can’t find it. I’m trying to get that restored, which is a slow process. There are quite a few bureaucratic channels to ensure that she has no living relatives who might object to the restoration. It’s now sitting with the bishop, and I don’t know how long bishops take! I have been very optimistically setting up a crowdfunding page, which is on its way at some point in the future. And then Eliza can be properly recognised.

UPDATE (31 Mar 2022) The crowdfunding page is now live!

Explore the most popular recipes in Modern Cookery for Private Families on ckbk, and browse Annabel Abbs own top 10 cookbook recommendations.

Recipes from modern cooks inspired by Eliza Acton

Sign up for ckbk's weekly email newsletter

More features from ckbk

Q&A with Sharon Wee

Sharon talks about her book Growing Up in a Nonya Kitchen.

Advertisement