Advertisement

Digging up the history of hot chocolate

1 December 2021 · From the Chopping Board

TALES FROM THE CHOPPING BOARD

In this series, ckbk users talk about the cookbooks, authors, and recipes that have influenced them: helping them get the measure of a tricky dish, understand a culinary technique, or build an appreciation of the foods, places, ingredients, or cultural history of a particular regional cuisine.

This is a space for cooks to share their thoughts on cookbooks and related topics. If you’d like to join the discussion and contribute a piece, drop us a line.

Canadian heritage consultant (and hot chocolate aficionado) Jane Severs writes about how a few delicate 17th-century porcelain fragments uncovered at an archaeological site in Newfoundland led her “down the rabbit hole,” to unravel the history of chocolate in the New World.

In her ensuing investigations, with help from ckbk, she found out about cocoa’s Mesoamerican roots, its status as a European luxury good – and discovered some contemporary hot chocolate recipes that show how much the drink has changed (or not…) through the centuries.

By Jane Severs

One of the things I love about my ckbk subscription is that it gives me access to a crazy range of cookbooks: from brand-new releases to tried-and-true classics, encyclopedic reference tomes like The Oxford Companion to Food to pure food porn (have you seen Francisco Migoya’s desserts?). Then there are my personal favourites, which tend to have pithy titles like The Accomplisht Cook, or the Art and Mystery of Cookery, subtitled Wherein the whole art is revealed in a more easy and perfect method than hath been publisht in any language (1660 edition).

Now, I’m well aware that for most folks historic recipes and the foods they produce are, at best, objects of curiosity. I know this because I help run a historic cooking program at the Colony of Avalon, a 17th-century historic site and active archaeological dig in Ferryland, Newfoundland. I’ve heard school children scream and seen grown adults recoil in horror when offered a taste of a re-created 17th-century dish.

This really is a shame because, as authors like Regula Ysewijn and Annie Gray have shown, historic food tastes great (ok, most of it tastes great). But more importantly, historic food can give us real insight into the lives of the people who originally prepared and ate those dishes, and maybe spur some similar thinking about ourselves, and the foods we eat today.

Take hot chocolate as an example.

Down the rabbit hole…

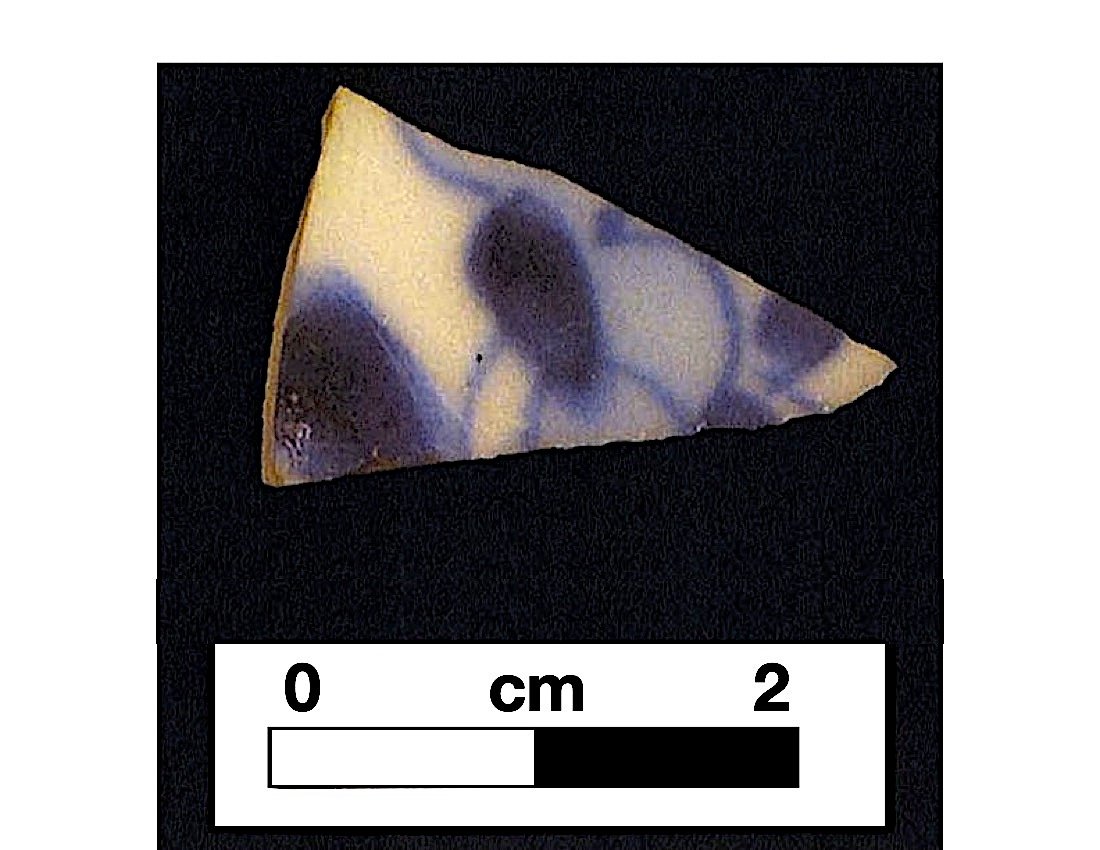

My journey down the hot chocolate rabbit hole began with a pair of cups. Actually, they were pieces of cup, found buried in a rubbish pile just outside a woman called Sara Kirke’s home. Turns out, these were no ordinary cups, which really shouldn’t have been a surprise since Sara Kirke was no ordinary woman.

Flashback to 1651. Sir David Kirke – military hero/pirate (depending in whether you were English or French), first Governor of Newfoundland, and Proprietor of the Colony of Avalon – is rotting in an English prison on charges of treason and tax evasion.

By 1654, he’s dead, leaving his wife Sara with four children, a third of his property, and a staggering amount of debt. Tearful tale? Guess again. Under her management, the Colony doesn’t just survive; it thrives! By 1660, Sara Kirke is running one of the largest business enterprises in Newfoundland, making her one of North America’s earliest and most successful female entrepreneurs.

And those bits of cup? Chinese porcelain! In 17th-century England, porcelain was a capital-L luxury good. Purchased at enormous expense and conspicuously displayed, it was material proof of its owner’s considerable taste, wealth and status. And in the rugged environment of 17th century Newfoundland… It was the kind of find that makes archaeologists’ hearts beat just a little bit faster.

Chocolate: a rich man’s drink?

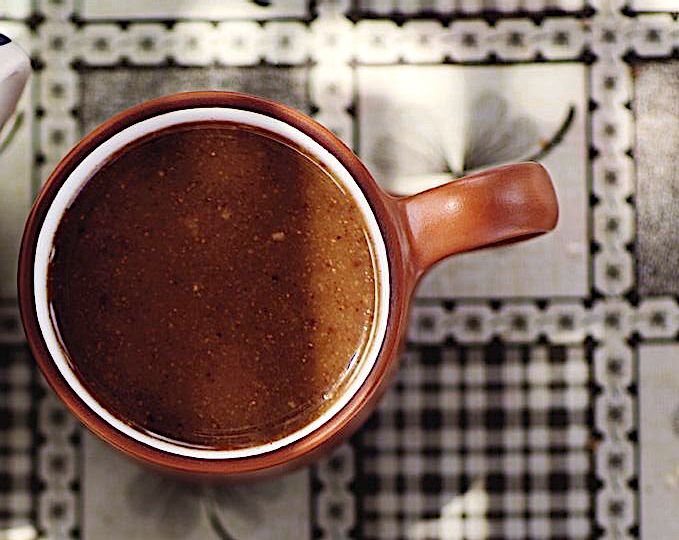

This particular style of cup was originally used by the Chinese to serve tea. In the west (where tea drinking was still a novelty) it was also used for drinking chocolate, a mixture of ground cacao, spices, and water, milk and/or brandy. The possibility that Sara Kirke drank chocolate from her cups is super exciting.

You see, in 17th-century England, chocolate was almost exclusively a man’s drink – make that a rich man’s drink. It was served and consumed not at home, but in exclusive, male-only chocolate houses where the noble and the notable gathered to discuss politics and business, to gossip and to gamble.

The remains of Sara Kirke’s residence in Ferryland, Newfoundland

Did Sara Kirke – colonial entrepreneur, stateswoman and patron – use chocolate as a way of asserting her place in a man’s world? Records of goods shipped from Portugal to Newfoundland in the second half of the 17th century show that Sara Kirke did have access to cacao in Ferryland. I could imagine this pioneering woman, sitting in the parlour of her mansion house in Ferryland, receiving an envoy, or discussing trade over a cup of chocolate (after all, archaeologists recovered the fragments of two cups).

On a whim, I Googled “17th-century hot chocolate recipes” and up popped Anya von Bremzen’s entry for Maricel’s 17th Century Hot Chocolate on ckbk. A mere $42 dollars worth of ingredients later and I was ready to whip myself up a pot of chocolate. The results? Rich, complex, bitter.

A taste of history

Dive further into ckbk’s search results for hot chocolate and you’ll see just how much this drink has changed… or not. Echoes of its 17th-century European past (and even further back, to its origins in Mesoamerica) can be seen in Bricia Lopez and Javier Cabral’s Champurrado recipe and in the flavours of Kirsten Gilmour’s Spiced Hot Chocolate.

And while chocolate is now accessible to the masses, its historical associations with luxury, decadence and even debauchery remain in recipes like Matt Lewis’ Adult Hot Chocolate, Chantal Coady’s Chocolat a L’Ancienne, or Peter Sherman’s Bacon-Hazelnut Hot Chocolate with Sugared Bacon and Smoked Marshmallows (because is there anything more taboo these days than copious amounts of bacon fat?).

Then there’s Ariane Resnick’s Armored Hot Chocolate with its additions of “grass-fed butter for inflammation reduction, MCT oil for fat-burning and antimicrobial properties,” and kava powder for its stimulating, or maybe relaxing, but definitely mouth-numbing qualities (Is it even safe to drink hot liquids when your mouth is numb?).

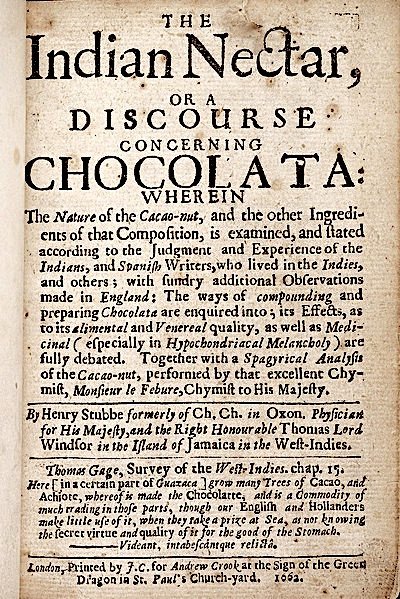

It reminds me of Henry Stubbs’ 1662 discourse on the medical benefits of chocolate, which lists musk and ambergris (a secretion of sperm whale intestines) as possible additions to the drink.

A reminder of my earlier caveat… most historic food tastes great.

A selection of ckbk’s hot chocolate recipes

Would you like to contribute a post to the new Tales from the Chopping Board section? Get in touch!

More ckbk features

Advertisement