Advertisement

Behind the Cookbook: Goose Fat & Garlic

26 December 2022 · Behind the Cookbook

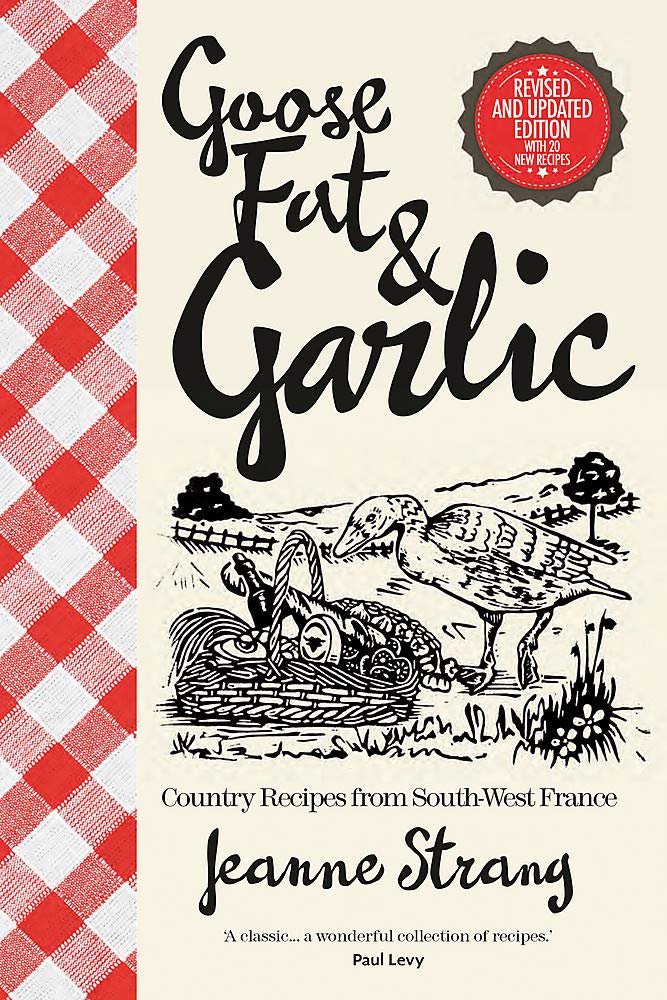

Jeanne Strang’s book, Goose Fat and Garlic, is devoted to the regional and highly seasonal dishes of rural South West France. Patricia Wells describes it as “a book with a ring of authenticity; a must for all cooks with a sense of curiosity and a dose of ambition.” The book has legions of devoted fans, among them Alison Stattersfield, who has recorded her progress in cooking her way every recipe in the book on her blog My Year of French Cookery. Below she explains why this book, and the cuisine of the region as a whole, means so much to her.

By Alison Stattersfield

I first saw a copy of Goose Fat & Garlic by Jeanne Strang in 1997, on the bookshelf of a friend who had just retired to a small village in the department of Lot, South-West France. I fell in love with this remote area, not least for its cuisine. I remember eating the rustic rillettes and confits, new tastes to me, and visiting the local markets, so tempting in the abundance and freshness of their produce.

Vallée du Lot

Five years later, almost on a whim, my partner and I found ourselves taking possession of an ancient key to a derelict house nearby, and holidays have been spent there ever since. I immediately bought my own copy of Goose Fat & Garlic, but it largely lay unopened, as I stayed within my comfort zone of cooking. However, learning to cook the French way became a growing ambition.

An early attempt at cooking from Goose Fat & Garlic

Then, I read Julie and Julia by Julie Powell, the captivating story of a young woman, with no cooking experience, tackling 524 recipes from Mastering the Art of French Cooking by Julia Child in one year. An idea started to form and, as retirement approached, I resolved to undertake my own “Jane and Jeanne” project. My dusty copy of Goose Fat & Garlic became the object of intense study, photocopied and spreadsheeted, as I planned how I would tackle its 225 recipes over one year. I remember the excitement of cooking the first recipe – La Garbure / rich soup with vegetables and preserved meats – on the 2nd December 2018 and writing my first post.

I stuck to my schedule to start with, but quickly realised that I needed to take a more considered approach, choosing recipes when ingredients were in season and / or apt for a particular occasion. So, as I approach the 200th recipe four years later, I wouldn’t say I have mastered the art of French cooking, but I do have a huge appreciation for this wonderful book. Jeanne and Paul Strang have been exploring the home cooking of the region, since buying an abandoned farmhouse in the Aveyron in 1961. They have sampled the local dishes, researched their ingredients, talked to cooks, and recorded the details for perpetuity. The result is a unique collection of traditional country recipes from South-West France.

Café des Touristes, a traditional restaurant in Marcilhac-sur-Célé, now sadly closed

The Aubrac – a beautiful upland region in the Auvergne, home to l’aligot, an increasingly popular dish across France

In the book, some recipes are grouped into familiar sounding chapters: la soupe (soup), les viandes (meat), les poissons (fish), les légumes (vegetables), les salades (salad) and les desserts (dessert). Others appear in chapters reflecting the key ingredients of the cuisine: les oies et les canards (goose and duck), le cochon (pork), la chasse (game), les fromages (cheese), les champignons et les truffes (mushrooms and truffles), les châitagnes (chestnuts), les noix (walnuts), les pruneaux (prunes), and le vin (wine).

There is a whole chapter devoted to cassoulet, so emblematic of the region, and tantalisingly described in the book as “a bean stew, perfumed with garlic and goose or pork fat and enriched by a variety of fresh or preserved meats”. There is only a short chapter on l’ail (garlic), as no specific recipes are included, because nearly every recipe in the book includes at least one clove! The remaining chapters reflect the humble origins of many of the recipes: la basse-cour (farmyard), les oeufs (eggs) and les plats de tous les jours (everyday dishes).

L’ail violet, a special variety of garlic grown around the village of Cadours

There are many things I love about this book. First, it’s not just a cookery book, but an introduction to the region. If you have already discovered this part of France, you will love it too, with stories that resonate. If you haven’t visited, you will want to! Each chapter is introduced with information on local traditions and anecdotes, written in a friendly, often humorous, style. The same is true of the recipes: most have a short introduction and helpful suggestions on accompaniments. The instructions are clear and encouraging and, without exception, they all work, and the results are delicious.

Here are three examples: I cooked le chou farci / stuffed cabbage for my book club. The introduction says “in England we consider the cabbage as one of the more mundane vegetables – redolent of school dinners … in France, le chou farci is something of a treat”. I was a little concerned as to which way things would go, but my group came down on the side of the French! I cooked le porc en cocotte aux châtaignes / braised pork with chestnuts for a dinner party. I didn’t have much time and felt like I was throwing everything together. But the results were fantastic and, on the strength of this one dish, our friends bought the book the next day. I cooked les perdrix aux choux / partridges braised on a bed of cabbage one Sunday lunch. The construction seemed a bit strange, and I had no idea how it would turn out, but I can still remember how mouth-wateringly tender this was.

My Goose Fat & Garlic project has led me to try lots of new ingredients. Le gratin d’asperges / asparagus baked in a cheese sauce was the first time I had cooked white asparagus, and very good it was too. While familiar with haricots, I had never eaten les haricots beurre / yellow haricot beans and now I am a convert. I have tackled lots of different cuts of meat, many overlooked or hard to find these days, for example les rognons de veau à l’armagnac / veal kidneys in Armagnac. I have learned to love rabbit too with many recipes to choose from, for example le lapin sauté au verjus / rabbit with verjus.

In the UK, I had to order salsify specially for le tourtière aux salsifis / chicken and salsify pie, but then found it growing in a neighbour’s potager (vegetable patch) in our village in France. Discovering sorrel was a thrill and now I look forward to buying it in the market each spring. L’omelette à la purée d’oseille / omelette with a purée of sorrel is described as “after a truffled omelette, probably the most delicious omelette of all” and I wouldn’t disagree. And I tried turnips – not the winter sort, rather those small white-and-purple globes that can also be found in the market in spring (see Les navets glacés / glazed turnips).

Salsify growing under our noses - in a neighbour’s vegetable garden

Oseille (sorrel) is a treat in the spring

Comparing Goose Fat & Garlic to other French cookery books, I have come across two that are in the same genre: Mourjou: the life and food of an Auvergne village by Peter Graham and The Auberge of the Flowering Hearth by Roy Andries de Groot [both of which are also available on ckbk]. The first is by a British author who wrote of the many meals he ate in Mourjou, a remote French village in the Auvergne, where he lived for more than four decades. The book is described in his Guardian obituary as “replete with local colour, served with gentle but consistent scholarship”. The second is by a British American food writer who became entranced by the extraordinary range of seasonal, local cuisine offered by two middle-aged women who ran an auberge in the Valley of the Grande Chartreuse in the French Alps. All these books evoke a simpler time, when seasonality was valued, and local ingredients were used in tried and tested traditional recipes, to produce hearty, delicious meals.

Another book covering the same region is The Cooking of South-West France by Paula Wolfert, though the approach is different, focusing on the making of the food. Only some 20 recipes overlap with those in Goose Fat & Garlic, and so the two complement each other. Other books which I have enjoyed exploring during my French culinary adventure include The French Kitchen and The French Market by Joanne Harris, Sud de France: The food and cooking of Languedoc by Caroline Conran, and Ripailles: traditional French cuisine by Stéphane Reynaud. Sometimes I like to check more general books such as French Classics Made Easy by Richard Grausman, French Countryside Cooking by Daniel Galmiche, and Glorious French Food by James Peterson.

But Goose Fat & Garlic will always be my number one cookery book. Before I started my project I contacted the author, Jeanne Strang, to let her know what I was planning, and then kept her up to date with progress. Jeanne was very gracious, always responding, even though she had no idea who this crazy woman was. After a few years, we were invited to lunch at Jeanne and Paul’s home in the Aveyron. Their beautiful house was just as I had imagined, full of lovely old features and traditional objects, with a huge walk-in fireplace where joints are still roasted. We had la crème de courgettes à l’huile de noix / courgette soup with walnut oil and it didn’t disappoint.

Some quotes from the book

On soup: Another way in which extra weight is given to a soup is by adding le farci. This ball of savoury stuffing is either cooked inside a chicken in the pot or is wrapped up in cabbage leaves before being popped into the soup. This “treat”, as it often was, was really a way of stretching a small quantity of meat.

On duck: A properly prepared magret is one of the most delicious and succulent dishes in the repertoire of the South-West.

On pork confit: Like all confits, it will have acquired a nutty maturity which no other method of preserving food can achieve.

On pork skin: South-Western cooking is unique in its use of the skin off a pork joint which is not cooked with the roast to make crackling but is cut off and preserved separately in its own fat – couennes confites – to enrich soups or vegetable dishes. Perhaps the most delicious way these are then used is in combination with green lentils, which need some kind of fat to enrich them and their sauce.

On garlic (where 40 cloves are suggested): There is no reason to fear the quantity of garlic. Long gentle cooking tames the flavour as it does the sinews of the meat.

On cabbage: In England we consider the cabbage as one of the more mundane vegetables – redolent of school dinners. In France le chou farci is something of a treat, combining meat and vegetables. It used to be specially prepared on Saturday night and cooked slowly on the corner of the fire next morning while the family went to Mass.

On sorrel: The deliciously fresh, lemony taste is a wonderful contrast to the rich, fatty dishes that compose a large portion of the peasant cuisine.

On broad beans: La soup aux fèves à l’ancienne…was prepared at haymaking when it was made at breakfast time and kept hot until midday, tucked under the eiderdown.

On cèpes: We have seen how useful dried cèpes can be in stews and civets. They go particularly well with game birds, both flavours evoking the floor of the chestnut woods where they come from.

On prunes: It is strange how the French succeed even with those foods which were most hated in childhood and which never get given a second chance.