Advertisement

Author Profile: David Thompson, author of Classic Thai Cuisine

2 February 2026 · Author Profile

Australian chef David Thompson’s critically acclaimed cookbooks on Thai cuisine, together with his hugely successful high-end Thai restaurants, have been instrumental in bringing the range and diversity of Thai cuisine to an international audience. This week we are delighted to add David’s first cookbook, Classic Thai Cuisine, to ckbk’s collection. In this latest author profile, fellow Australian and long time friend Roberta Muir talks to David about his career, his influences, and the in depth research which has gone into his cookbooks.

By Roberta Muir

Chef David Thompson fell in love with Thailand—its food, people and culture—on a holiday to Bangkok in the mid-1980s.

Never one to do things by halves, when David became enchanted with the nebulous world of Thai cuisine he set out to learn all he could about it, including mastering the language. On an early trip to Bangkok, he apprenticed himself to an octogenarian cook who had learned her craft in the royal palace. He recalls: “Khun Sombat had exacting culinary standards, everything was made by hand, her cooking was instinctive and spontaneous, relying upon taste and smell, not slavish adherence to measurements – and she completely transformed my understanding of Thai cuisine. When I tasted her cooking I realised that Thai food is one of the world’s greatest cuisines.”

David drew inspiration from recipes of the Thai court – such as the simple sounding, but in fact highly elaborate, noodles with prawns and garnishes from a 1935 anthology of recipes by Princess Yaovabha Bongsanid, daughter of King Chulalongkorn (Rama V). David credits the King with helping to raise Thai cuisine to unprecedented heights of refinement while the king himself often favoured simple dishes such as rice with prawn paste.

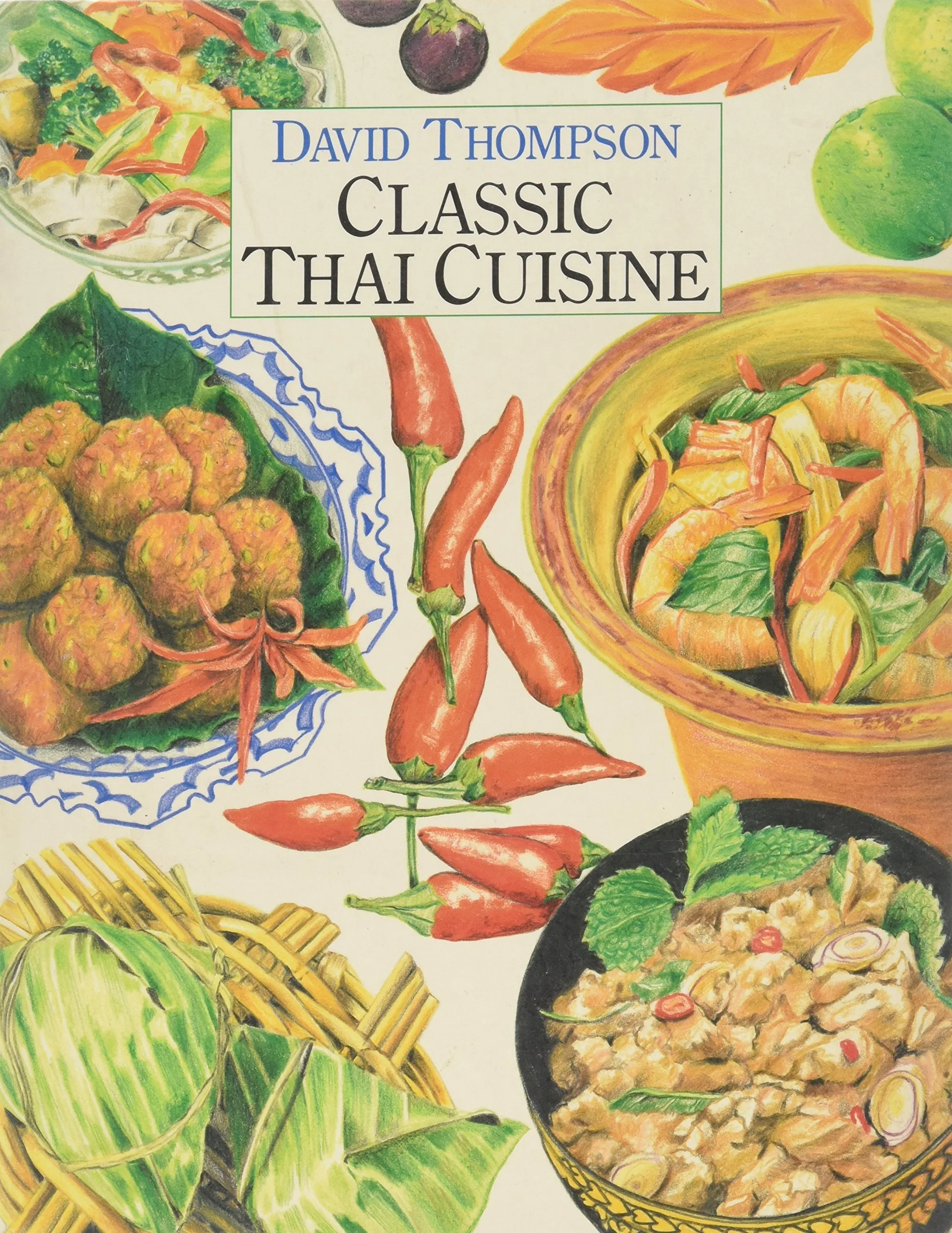

Classic Thai Cuisine, David Thompson’s first cookbook

David also learned much about Thai food by translating memorial books created to honour high-ranking Thai women after their deaths. These often contained their favourite recipes, such as the trout with caramel and fish sauce he found in the book of M.R. Yingdteung Sanitwongse.

By the early ‘90s, in a bistro at the back of a pub on Darley Street in the inner Sydney suburb of Newtown, David was cooking Thai food unlike anything Australia had ever tasted. This was when he wrote Classic Thai Cuisine, his first cookbook, published in 1993.

David continued introducing Australia to Thai cuisine throughout that decade, moving Darley Street Thai across Sydney to fancy new digs in Kings Cross, and opening the more casual Sailors Thai in The Rocks a few years later. I met him at Sydney Seafood School in 1997, just a few weeks after I took over the reins there, and it changed my life forever. During the following 20+ years David taught over 30 classes at the School, each one a masterclass not just in Thai cooking, but also in the culture, mindset and traditions of Thailand and its people, who David came to understand with an insight rare in someone not born in the country.

The first thing David explains to anyone wishing to master Thai cuisine is the principle of rot chart (harmony of flavour), where sweet, sour, salty and hot are balanced not just across one dish but through the dishes chosen for an entire meal. A balance of textures—obtained through a selection of dishes that are wet and dry, crisp and soft – is also important. David explains that the heat of a basic sour orange curry of freshwater fish and snake beans can be complemented by a gentle dish of steamed egg custard with pork and a simple dry dish of shredded salty beef; while the heat of a fiery nam prik nuum (northern chilli relish) might be assuaged by a delicate omelette soup with refreshing crunchy bean sprouts and the sweetness of crispy fried pork belly in chilli jam (which he warns is irresistibly more-ish).

David has always stressed that a Thai meal must consist of several dishes placed on the table together and used to flavour the steamed white rice that is the core of every proper repast. So fundamental is rice to Thai cuisine that these accompanying dishes are collectively called ‘gap kao’ (with rice) and he explains: “even at the most affluent tables a meal consists of at least fifty percent rice, much more in poorer households.”

A balanced Thai meal contains at least four dishes, David elaborates, often more. Thais are a gregarious people and mealtime is a communal activity. The more people at the table, the greater the variety of dishes that can be enjoyed – and Thais love variety. A typical meal includes at least a curry, a salad and a soup, plus a steamed, grilled, stir-fried and/or deep-fried dish. Also essential is a relish (nam prik or lon), including David’s favourite nam prik kai kem made with salted duck eggs, plus other condiments like ajat, the pickled cucumber relish especially popular with fried foods such as Thai fish cakes. Sugar, lime, fish sauce and chilli are typically also on the table for diners to season the food to their preferred level of sweet, sour, salty and hot.

The chilli jam used with crispy fried pork is equally good in these Clams with Chilli Jam, also from Classic Thai Cuisine

Noodles, introduced from China, are the only category of dish that isn’t served communally. Perhaps that’s why recipes such as the simple noodles with pineapple & prawns is often favoured for a quick lunch.

Except for noodles, any food eaten without rice is considered a snack, not a meal. And Thais are inveterate snackers, traditionally only eating one main meal a day with rice, often having noodles for lunch, and snacking on savoury and sweet treats throughout the rest of the day. David explains that “… by some perverse logic, snacks are not even considered real food, merely a pleasant diversion to while away any spare time. Food, and snacks especially, is an entertainment to the Thais, albeit a serious one.”

Thailand is the only southeast Asian country that has never been colonised. It has however drawn influences from its neighbours and immigrants over many centuries and made their dishes its own. Chinese noodles are just one example, massaman curry, made with the dried spices of Persia and India, is another. While a dessert of golden egg threads is inspired by the Portuguese traders who arrived in the 16th century.

David also gives a recipe for steamed black bream with ginger and shallots that is very reminiscent of the classic Chinese dish of steamed fish flashed with hot oil. The Thais have made it their own with the addition of chillies, white peppercorns and oyster sauce.

As the title suggests, this book is full of the classic Thai dishes the western world has grown to love, from fish cakes, spring rolls and satay to hot & sour soups (tom yam), som tam (green papaya salad), larp, green curry and kaow niaw (sticky rice with mango).

There are also dishes that David and his disciples have made popular among lovers of authentic Thai cuisine, including miang (bite-sized, leaf-wrapped snacks), steamed curry, stuffed squid, grilled chicken with sweet chilli sauce, and—my favourite—dishes deep-fried with a paste of coriander root, garlic and white peppercorns.

David gives recipes for lesser-known regional dishes too, discovered on his extensive travels throughout the country, like the laksa-style kao soi noodles and Burmese-style pork curry from Chiang Mai in northern Thailand. There are dishes translated directly from private anthologies such as a relish of minced prawns in coconut cream and some from the first Thai chefs to inspire David’s culinary journey like chicken curry with ginger from the late Chalie Amatyakul. And of course there are dishes from his mentor Khun Sombat, including her lon of yellow beans in coconut cream that David likes to serve with fiercely hot dishes like pork with snake beans and chilli paste.

David says that “Thai food is very adaptable and new dishes are made by the judicious addition of new ingredients.” Thai recipes are not prescriptive, allowing each cook to use what is at hand and season to their own taste. Perhaps reflecting the paucity of availability of authentic southeast Asian ingredients in the 1990s when he was writing, David helpfully offers alternatives in many recipes. In a salad of green mango and squid, for example, he recommends replacing green mango with tart green apple dressed with a little lime juice rather than using a partially ripe mango.

The flexibility of Thai recipes also means that proteins can easily be substituted and, given many Thais are Buddhist, David also frequently offers vegetarian variations to his meat and seafood recipes. Saying in the introduction to his tom kha of mud crab: “Westerners normally associate chicken with this soup, but as with the tom yams, it is not so limited. Any meat, poultry, seafood or vegetable may be substituted for the mud crab. Tofu, oyster mushrooms or baby corn go particularly well if a vegetarian soup is desired.”

Ready for a world stage by 2000—just weeks after preparing the most delicious pandan-flavoured coconut pudding as the dessert for my wedding feast—David and his Thai partner Tanongsak moved to London to open Nahm in The Halkin Hotel. Breaking all the rules of traditional fine dining, Nahm quickly became the first Thai restaurant ever to receive a Michelin star.

Nine years after opening in London, the Aussie chef brought Thai food home to Thailand, opening Nahm in The Metropolitan Bangkok. It was named Asia's Best Restaurant in the World's 50 Best Restaurants list and received its first Michelin star in 2017 when the famous red guide expanded into Asia. David’s dedication to Thai cuisine was acknowledged with a Lifetime Achievement Award at Asia’s 50 Best in 2016. In 2025 he received the inaugural Michelin Guide Mentor Chef Award, with the judges saying: “Many of Thailand’s leading chefs have trained in his kitchens, carrying forward his respect for tradition and commitment to excellence. Though not Thai by birth, his career has been devoted to preserving, teaching, and elevating Thai cuisine. His influence continues to shape Thailand’s culinary scene, making his impact both profound and enduring.”

David has spent much of the 21st century globe-trotting or at home in Bangkok and is committed to protecting the history and legacy of Thai food. Today he oversees restaurants around the world, including Long Chim Perth and Riyadh, Aksorn and Chop Chop in Bangkok, and Long Dtai in Koh Samui.

As with his restaurants, David’s subsequent books have reached a global audience. Thai Street Food (published in 2009) has been through successive editions and Thai Food (2002) is available in multiple languages. Meanwhile Classic Thai Cuisine is where it all began—a snapshot in time when the western world was just discovering authentic Thai food and a primer on the essentials of traditional Thai cuisine. Every cook can find inspiration in its pages, from levelling-up daily meals with basic recipes—like the tangy sweet lime dressing used in saeng wa of grilled prawns or the spicy tamarind sauce served with grilled fish – to going all out and creating a traditional Thai meal of curries, soups, salads, relishes and other dishes.

Watch Roberta’s interview with David Thompson

More ckbk features

Charlie Cart’s Carolyn Federman with ideas on how to help young cooks build the basic skills they will need

Pastry chef Luciana Corrêa with a beginner’s guide to the indulgent world of cakes

Max Tan looks at Jennifer Brennan’s pioneering title on Thai cooking

Advertisement