Advertisement

Gut instinct: ckbk’s fermentation collection

23 November 2021 · Discover ckbk

Coffee, salami, wine, bread, cheese, beer… you don’t need to look hard to find fermented foods in our everyday diets, and many of the techniques used to produce them have been around for centuries.

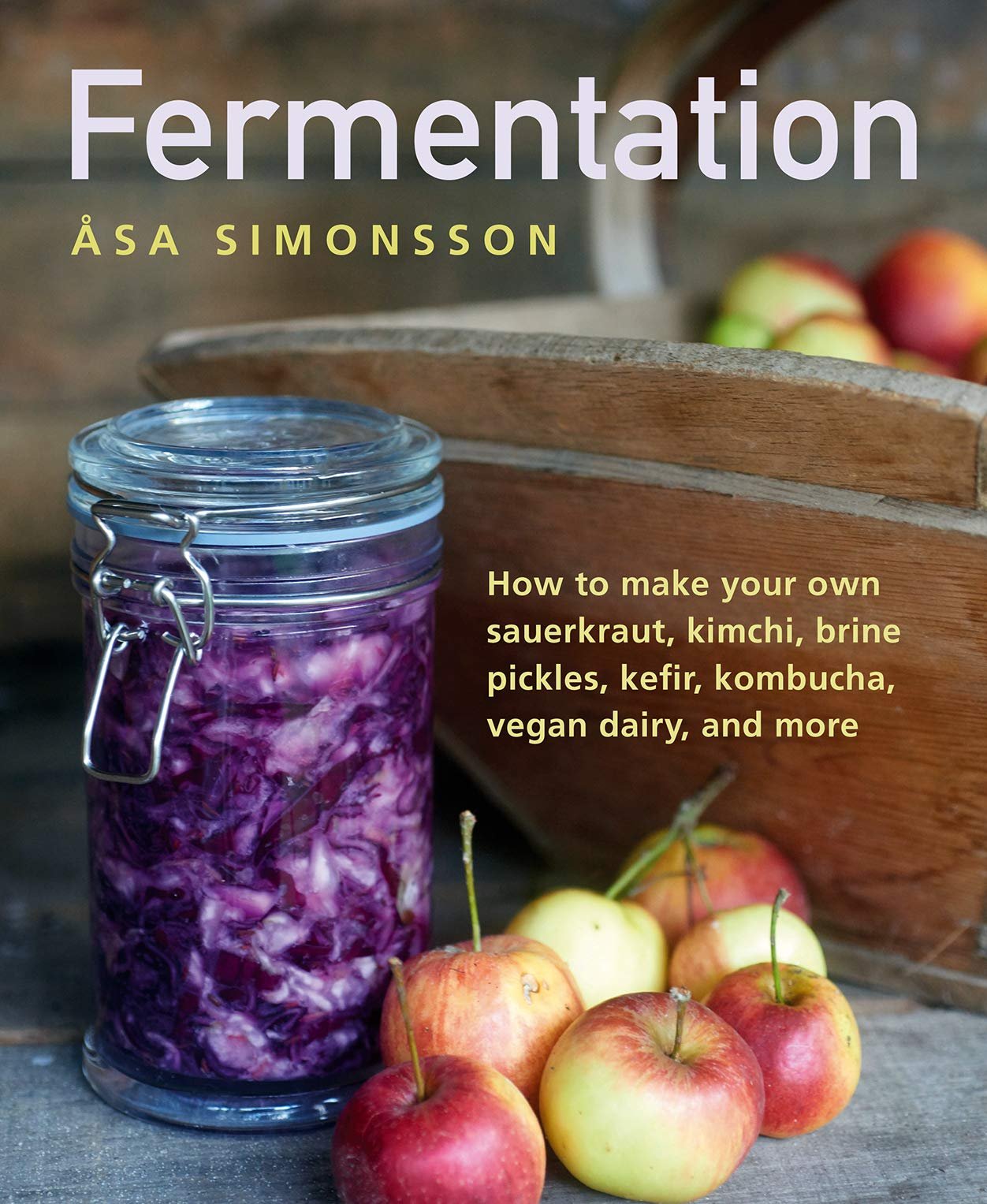

Inspired by Asa Simonsson’s new-to-ckbk title, Fermentation, we take a (good) bacteria-fueled journey through the ckbk collection to discover more about the ancient art and science of this method of preserving and enhancing food.

From Korean to Japanese, and from Burmese to Indian, German, and Russian recipes, these delicious – and, when you think about it, quite ingenious – ways of developing flavor often turn out to have a myriad of other benefits too. We caught up with Simonsson for advice about how to get started in fermentation, and we delve into the range of recipes and techniques covered by ckbk authors.

For starters

If you’ve not heard about the gut microbiome, where have you been? It’s made up of trillions of bacteria, fungi, and other microbes and plays an important role in digestion and the immune system. Heartburn, acid reflux, food allergies, high cholesterol, depression, and diabetes are just some of the conditions linked to the proportions and type of bacteria in the gut microbiome. Probiotics, which occur in many fermented foods, can help replace or supplement damaged gut flora, as Simonsson explains in her book.

But aside from all that, fermented foods are some of the tastiest things you can eat! Pickles, miso, kimchi, fish sauce, soy sauce, tempeh... the list goes on and on. We asked Simonsson for some advice for the first-time fermenter. She recommended keeping things simple: “People tend to be scared because [fermenting] involves bacteria, but not all bacteria is bad. The bacteria involved in fermenting is ‘good’ bacteria, also referred to as probiotics.”

“The same bacteria in our gut microbiome, which is also a large part of our immune system, will protect against ‘bad’ bacteria. As long as simple hygiene is used (the same kind of hygiene that should always be used in food preparation), it is highly unlikely that other bacteria or fungus will enter the ferment.” She advises following a recipe the first time so that you get the right quantities of salt to vegetables: “If you use too much salt, it will not be nice to eat, and if too little salt, your veggies may come out soft or even soggy.”

Asa Simonsson’s book, Fermentation, is a thorough introduction to what can be a daunting subject with 64 recipes for vegetables, drinks, and sweet dishes.

Fermenting all over the world

Our new ckbk collection, fermented recipes from around the world, is testament to the many ways that humans have found to ferment ingredients all across the planet, and the tasty uses for them. As Simonsson writes in Fermentation: “Our knowledge of fermentation could be as old as the human race itself.”

Sauerkraut is one of the first things many people think of when they hear the word fermentation, and there are umpteen ways to ferment a cabbage! Actually cabbage was fermented in China more than 6,000 years ago at a time when cabbage juice was also prescribed for good health. Simonsson recommends sauerkraut as the ideal first ferment. She says: “Using red [cabbage] or a combination of red and white tends to come out more crisp in my opinion, but just white is good too. Also, this simple type of sauerkraut is often well-liked by most people, including the beginner and even children.”

Try combining fermented and fresh vegetables. Find more ideas in the ckbk mastering fermented vegetables collection.

No discussion of fermenting cabbage could fail to mention the mighty kimchi. In Korean Home Cooking, Sohui Kim’s Baechu Kimchi is a contender for the ultimate recipe. Kim describes it as “the master kimchi recipe, the one that non-Koreans think of when they hear the word kimchi – baechu means ‘cabbage.’ It’s also known as poggi kimchi: poggi means ‘fold,’ since you fold up whole cabbages and ferment them.” This version is made with fermented seafood (either salted shrimp, fish sauce, or even freshly shucked oysters!) and a paste made from sweet rice powder. Add it to a pork stew (Kimchi Jjigae) or fried pancakes (Kimchi Jeon).

Kim’s Dongchimi is another recipe to bookmark for when you can get hold of white radish (mooli). Or how about fermenting turnips!? Looking to Japan, Aya Nishimura’s Japanese Food Made Easy uses a type of turnip called ‘Tokyo turnips’ (or Japanese turnips) in her version of the Kyoto specialty Senmaizuke (senmai means ‘a thousand slices’).

Robert Danhi’s Southeast Asian Flavors reminds us how crucial fermentation is in all cuisines, but especially Southeast Asian: “The importance of Thai fish sauce (nam pla), a product of fermented fish, cannot be overstated.” Shrimp paste, oyster sauce, light soy sauce, and yellow bean sauce also give what he describes as a “fermented umami bomb.” For a vegetarian umami bomb, tua nao, made of fermented soybeans and popular in northern Burma and Thailand, is worth seeking out. Naomi Duguid’s Burma: Rivers of Flavor has a recipe for Fermented Soybean Paste, a delicious replacement for shrimp paste.

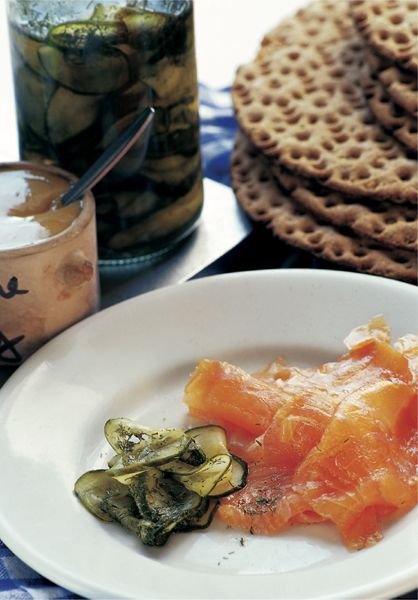

Simonsson’s heritage is Swedish and there are traditionally lots of Swedish fermented foods to be served at Christmastime. Gravadlax of course – “very easy to make yourself and divinely good, and a must on the Christmas table” – and red fermented cabbage, which is served with ham in Sweden. She suggests it would work well with turkey too. Kimchi Brussels sprouts, anyone?

Preserving techniques

Simonsson tells us there are two main techniques to fermenting vegetables: “One way is when you add liquid to the vegetables to provide the right circumstances for the fermentation process to start and another way is when no liquid is added, but where the liquid inside the vegetables is used to create the same type of environment.”

In her book these techniques are called brine ferment and dry ferment. The brine ferment produces more liquid and looks similar to pickled vegetables. Sauerkraut can be made both ways. Our new ckbk fermented vegetables collection shows the range of ingredients you can use with these techniques – a handy way to use up a glut of vegetables or fruit (such as rhubarb or even wild garlic).

Raspberry and Apricot Kombucha from Asa Simonsson’s Fermentation.

Drinking for gut health

Fermented soft drinks such as water kefir, kvass, kombucha, or ginger beer are fun to make and a worthy alternative to standard fizzy drinks for children. You never know, your kids might even acquire a taste for milk kefir! Our fermented drinks collection is the best introduction to fermented soft drinks – note the Spiced Winter Kvass, a lovely Christmassy-flavored kvass.

We would also highly recommend adding fruit to make a second fermentation of kombucha – Simonsson’s Raspberry and Apricot Kombucha is a fine example of this technique. But if you want to up the alcohol level of your ferment, look no further than the late Roger Philips’ wonderful Wild Food with its selection of fermented drinks made from wild ingredients. Cheers to that!

We have barely scratched the surface of fermenting (we haven’t even mentioned sourdough!), but we hope this overview has given you some routes into the culturing of food for good health, and of course good taste.

Taste fermented food from all over the world in our new ckbk collection, or scroll through the recipes above for a selection of fermented vegetables.

More ckbk stories

Just like grandma used to make

We explore grandmother-inspired recipes from all around the world, sourced from our vast cookbook collection.

Author Profile: Sharon Wee

Sharon talks to ckbk about her influential book, written in memory of her mother, and explains the intricacies of Peranakan food culture.

Behind the Cookbook: 30 years of Pied à Terre

We spoke to restaurateur David Moore who looks back on the restaurant’s history and the making of the book.

Sign up for ckbk's weekly email newsletter

Advertisement