Advertisement

A route through ckbk’s French cookbook collection

24 July 2020 · Discover ckbk · Regional cooking

Illustration: Shutterstock

Loving French food is easy. Finding exactly what kind of French food to cook, learn about and discover is a bit more complicated. This route through France’s regions, chefs and cooking styles will help you find the best of French cuisine.

French cooking – be it traditional or modern, classic or rustic – is alive, well and simmering along rather nicely. The 25 French cookbooks in the ckbk collection run the gamut, including classic French cuisine from the early 20th century, to defining recipes from the maverick bistronomy movement. Titles from famed chefs such as Auguste Éscoffier and Pierre Hermé are among the ‘most popular’ among users, and titles from Richard Olney and Paula Wolfert figure prominently among the top tiles curated from ckbk’s expert contributors.

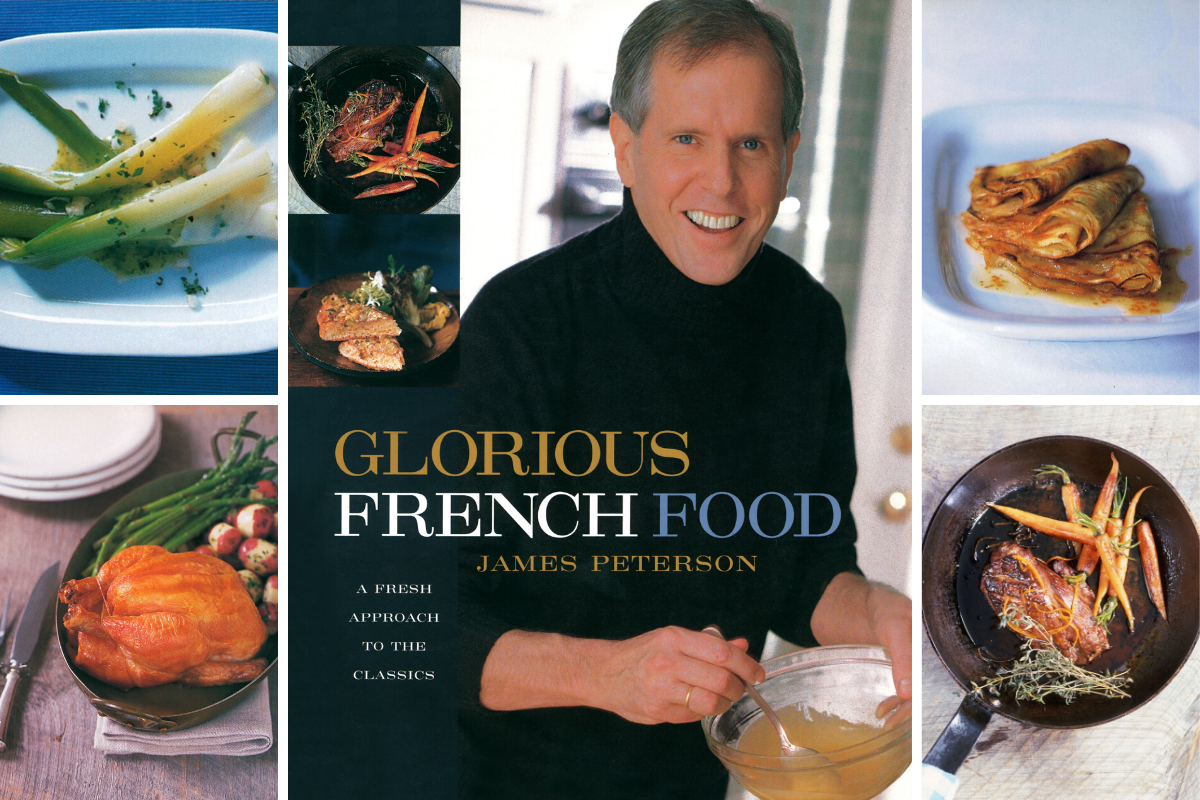

Loving French food is the easy part. Defining exactly what French cuisine is, isn’t quite so straightforward. There is no single style of French food, as American chef, cooking teacher and author James Petersen eloquently explains in his Glorious French Food (2002), listing la cuisine classique (of the sort served in noble households until the French Revolution), la cuisine bourgeoise (as cooked in “well-run households” before the Second World War) and the inventive, integrative nouvelle cuisine of the 1970s. “There is also la cuisine du terroir, hearty regional cooking made with local products and reflective of centuries of eating habits in various parts of France,” Petersen writes.

Cooking styles of the north, south, east and west of the country vary widely, as does the food of mountainous regions and seacoasts. Yet French cooking shares a common DNA, the same love and regard of food and ingredients, underpinned by technique that gives it a distinctive, if undefinable quality. There may be no single ‘French cuisine’ but you know it when you taste it.

Exploring regional France

Britain and France are separated by just a narrow body of water but their cuisines are worlds apart. While there are many brilliant French chefs working in the UK, it’s fair to say that British food lovers have been more inspired by French gastronomy than vice-versa, and there’s a long tradition of British cooks and food writers finding their voice and their métier on the other side of La Manche.

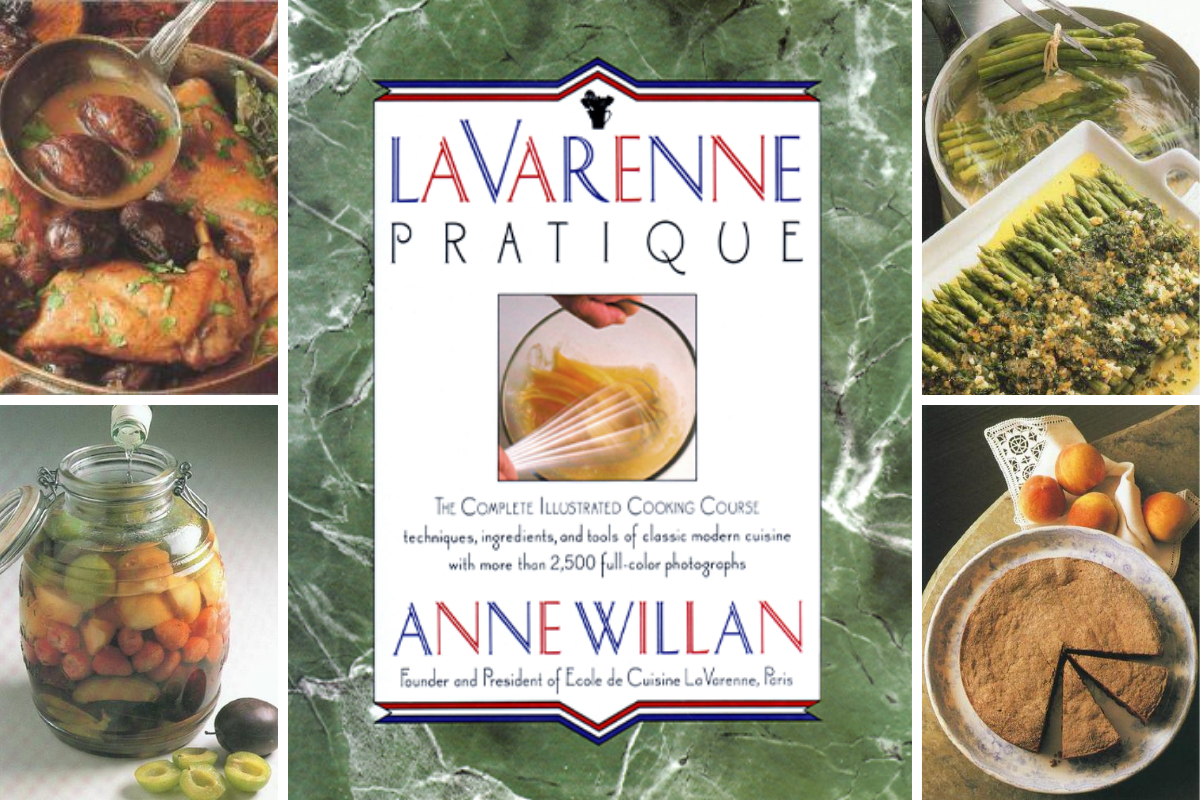

One of the most influential of these Brits abroad is Anne Willan. Originally from Newcastle in the north of England, this Cambridge grad was founder of La Varenne cookery school in Burgundy and Paris, which she ran from 1975 until 2007.

In her meticulously researched French Regional Cooking (1981), Willan divides France into 12 gastronomic regions, and writes about each with respect and authority – and what comes across strongly is her love for the country. “I have written this book because I love the French way of life and, it goes without saying, French cooking,” she writes. Diving into recipes such as Cotriade Bretonne, a fish stew from Brittany, and Corsican Stufatu give an idea of the range of Willan’s expertise.

Written decades later, her The Country Cooking of France (2007) is an edible roll-call of some of France’s best and most typical dishes, perfected over many years, including, of course, frog legs. If you try one recipe from this book, make it La Chasse Aux Escargots, a snail dish from her adopted home in Burgundy, which comes with instructions on how to capture and prepare the little creatures before cooking them in white wine and herbs.

Legendary raconteur and gourmand Keith Floyd was introducing the English-speaking world to the delights of French cooking at about the same time as Anne Willan was writing and teaching, but it would be difficult to find a more different voice than Floyd’s. Outspoken, irascible, a proud imbiber (no meal or cooking session was complete without plenty of vino), and an eloquent and enthusiastic guide to French cuisine. Reading his books now (and watching videos of his BBC series) is a reminder that food ought to be fun.

In Floyd on France (1987), a bow-tied Floyd introduces readers to no fewer than five recipes for snails: Charentes-style (in meat sauce), Burgundy-style (with parsley and shallots), snails ‘Francoise du Pré’ (with mushrooms, brandy and cream), Alsace style (cooked in Riesling) – but it’s the Burgundy-style escargot that are the most quintessentially Floyd, made with bacon, ham and peppers and two whole bottles of red wine – to serve four.

Heading to the south

More than any other region of France, it’s the south of the country that has captured the culinary imagination of countless English-speaking food writers. The wildly beautiful sweep of coast that lies on the Mediterranean, from Pérpignan to Montpelier, and Marseilles to Nice, has numerous devotees, as does the Basque country near the border with Spain on the Atlantic coast.

Iowa-born Richard Olney is required reading for lovers of French food. Although the recipes in his classic Simple French Food (1974) come from all over France, it’s the cooking of Provence, where he lived for many years, that most inspired him.

Olney was a mentor to Alice Waters of California’s Chez Panisse fame and, as Mark Bittman writes in the book’s introduction, “Olney’s love of southern French food … had a bigger impact on the development of California cuisine … than any book of its time.” Olney’s emphasis on simplicity holds true too, as concise recipes for Potato Tart and Chicken with 40 Cloves of Garlic prove.

Four takes on a Provencal classic, Bouillabaisse

The region has been a source of culinary inspiration for other prominent food writers too (and continues to be so today). Inevitably, recipes for particular regional classics pop up in numerous cookbooks, and considering the authors’ takes on a single dish makes for fascinating comparisons. Take Bouillabaisse, for example.

Mireille Johnston was born in Nice so it’s no surprise that her version of Bouillabaisse in The Cuisine of the Sun: Classical French Cooking from Nice and Provence (1990) is classic – and fairly complex, with a lengthy ingredients list that includes fish heads and 2–3 whole crabs – although, helpfully, the fish included can be easily found outside southern France. Classic flavorings such as dried orange rind, pastis and, of course, saffron, are used – and there are two recipes for rouille, the garlicky sauce that accompanies this fish stew.

At the other end of the simplicity spectrum is Leslie Forbes’ version from her A Table in Provence by (1987). The book itself has a travelogue feel to it – where to go, what to eat, history and recipes. Her Bouillabaisse Marseillaise is a simplified version but calls for all the classic French local fish (no substitutions for those outside the Med). Unusually, the soup is just seasoned at the end with saffron, not cooked with it, and there’s no rouille to serve with it.

Geraldene Holt’s Soupe de Poissons recipe from her French Country Kitchen (1987), though not strictly speaking Bouillabaisse, as it comes from Nîmes, west of Marseille, is something of a happy medium, flavored with garlic, tomatoes and saffron and served with a rouille. There’s no aniseed-flavored pastis but is instead made with red wine, and is fairly quick and straightforward.

In her recipe for Languedoc Fish Soup in Sud de France (2012), Caroline Conran writes: “The Languedoc Bouillabaisse is an aromatic Mediterranean fish soup containing garlic, saffron and fennel, but, unlike the Marseillaise version, this one shares the basic chowder theme of fish with bacon.” Made with clams and mussels and flavored with saffron (and served with rouille), garlic and bay, it does have similarities to New England-style chowder, as she points out.

From the Atlantic side of southern France, from the city of Bayonne in the Basque country, comes Paula Wolfert’s recipe for Fish Soup Basquaise from her The Cooking of Southwest France (1987, 2005). It’s made with mussels, boneless fish fillets and cooked crabmeat, so it’s not too taxing on the prep front. There’s no saffron in this dish but the recipe makes much of the locally grown piment d’Espelette, which is gently spicy and richly flavored and gives the dish kick.

Making sense of French cooking

French food, wine, cuisine – the whole way of French life has been a magnet for the gastronomically minded of innumerable countries. These two books from American-born writers who have lived or made their home in France, make fascinating reading because they give real insight into French cooking and local life.

In Hows and Whys of French Cooking (1974), author Alma Lach, who has been referred to as ‘Chicago’s Julia Child,’ focuses on making French food understandable to American palates. A thoroughly practical book that beautifully explains the French approach to cooking. From making basics such as beurre manié and crème pâtissière to mastering soufflés and planning French menus, it’s all here.

A contemporary book from Emily Dilling, My Paris Market Cookbook (2015), proves that Paris still has pulling-power for young Americans such as this California-born Paris-dwelling author. A reliable guide for discovering the ‘proper’ markets of Paris’s neighborhoods, and for recipes based on quality, seasonal ingredients. Her recipe for chickpea pancakes (called socca in their hometown of Nice), tells you how to make this much loved street snack, and where to track them down in Paris.

Learning to cook the French way

So, what if you want to really get to grips with cooking French food? There are few better starting places than with Anne Willan’s classic La Varenne Pratique (1989). As well as writing cookbooks, Willan ran the esteemed La Varenne Cooking School in Paris and Burgundy. The book has sold more than 500,000 copies. Though sought-after, it’s no longer in print but recipes for basics such as Quick Puff Pastry and Chantilly Cream, and classic recipes such as Poule au Pot are so worth delving into.

In Glorious French Food, chef James Peterson writes: “I’ve taken a very un-French approach and combined every style of French cooking, drawing from refined and extravagant lunches, meals in truck stops and in people’s homes (both poor and not so poor), and my houseful of old cookbooks.” The focus is on ingredients, equipment, technique, and giving a fresh take on classics – and that includes everything from crudités and salads to quiches, soups and roasts. Petersen’s a knowledgeable, informative and friendly guide to French cuisine. His recipe for classic madeleines demonstrates just how unscary these little French cakes actually are to make.

Fellow American Richard Grausman (also a highly regarded cooking teacher) is author of French Classics Made Easy (2011), which includes plenty of detail in explaining nuts-and-bolts basics such as how to achieve the ultimate chicken consommé (which Grausman says “should be crystal clear, full of flavor, yet not too salty, and it should have a lovely color ranging from light gold to deep amber”) to soufflés – his Soufflé Problem-Solving Chart will fix all ills, from an uncooked bottom to uneven rising.

Classic French cuisine

To really delve into classic French cuisine, it pays to go back in time and to go the classics, and that will ultimately lead all the way back to Le Guide Culinaire (1903) by Auguste Éscoffier

Éscoffier’s masterwork is the place to start if you really want to ‘get’ French cuisine. There’s no need to follow the recipes meticulously – and, with nearly 5,000 recipes, trying them all would be a lifetime’s work – but reading them and being inspired by them is the key to understanding classic French cuisine, whether you’re a pro cook or just keen to know more.

Le Répertoire de la Cuisine (1914), written by Louis Saulnier, a student of Éscoffier, gives the bare-bones essentials to 6,000 classic French recipes, making it compact accompaniment to Éscoffier for professional cooks and scholars of French cooking and food history.

Revered chef X. Marcel Boulestin, who opened Boulestin restaurant in London in 1927, played an important role in demystifying French cooking for British audiences. If you think classic French recipes for the likes of Blanquette de Veau and Beignets Soufflés have to be long-winded and tricky, his book Simple French Cooking for English Homes (1923) will convince you otherwise.

To dig deeper into the backgrounds and personalities of France’s best known chefs, Quentin Crewe’s insightful chef introductions are required reading. Great Chefs of France (1978) is dedicated to a whole generation the great French chefs-patrons – Alain Chapel, Paul Bocuse, Jean and Pierre Troisgros, Madame Point… and many more.

Round out your knowledge of France’s great chefs by reading through the short recipe collections from three of the best, all published in 2014: Paul Bocuse My Best, Alain Ducasse My Best and Pierre Hermé My Best.

Beyond classic cuisine

There’s more – a lot more – to French cuisine that the classics, of course, and these two books take a deep dive into two quite different types of restaurant cooking.

In French Brasserie Cookbook (2011) by Daniel Galmiche the recipes from this French-born, UK-based chef are not of the Michelin star sort, but of the more casual style dishes found in good brasseries in various regions of France, from Confit de Canard to Tarte au Citron. It’s good, honest cooking of the sort you always hope to find in a proper French countryside brasserie. Galmiche believes that, “cooking French food doesn’t need to be complicated, and bringing brasserie dishes into the home is returning them to their rightful place.” This is the book to do just that.

Galmiche’s most recent book, French Countryside Cooking, was published in 2021, and takes inspiration both from his upbringing in the Franche-Comté region, and from his explorations of the countryside around his adopted home in Oxfordshire’s Chiltern hills. It offers a selection of dishes drawing on ingredients from field, forest and stream.

Food writer Fran Warde’s New Bistro (2009) rounds up some of France’s best, most memory-making recipes from casual eateries in eight regions of France, many collected from the restaurant owners themselves. Recipes such as Calf’s Liver with Bacon and Aligot Potatoes (from the Aquitaine region) and Barigoule Artichokes (from Provence) are the dishes on which fond memories of French holidays are made.

The ‘bistronomy’ movement arose among maverick, well traveled Paris chefs in the 1990s and the aim was to serve good, unpretentious, affordable food in casual surroundings – taking bistro cooking back to its roots, essentially, while not turning its back on innovation. Bistronomy: French Food Unbound (2014) by food writer Katrina Meynink gives a brilliant insight into this movement, which she describes as “top-notch cooking prepared with a haute cuisine touch and served in fun, relaxed surrounds.” If you want to give your cooking a cheffy, avant-garde flair, this is the book to go to, for genre-defining recipes, including some from top London-based chefs Adam Byatt (Barbecued Scallops with Seaweed Gremolata) and Anthony Demetre (Iced Lemon Parfait with Confit Fennel and Raspberries).

Off the beaten track

On the topic of mavericks (albeit writers instead of chefs), there are some cookbooks that are genre-defying, but nonetheless utterly unmissable. The Alice B Toklas Cookbook (1954) is one such. Written just during the Second World War by Alice B. Toklas, partner of American artist Gertrude Stein, it’s a snapshot of a particular place and time in history and deserves to be read like a novel (or an autobiography, which it sort of is). And you can cook from it too (the Haschich Fudge – “which anyone could whip up on a rainy day” according to Toklas – is one of the most popular recipes.

If you thought speedy cooking was a contemporary obsession, Édouarde de Pomiane’s Cooking in Ten Minutes (1930) will set you straight. De Pomiane was no slouch – he lectured at the Institut Pasteur and was a nutritionist and a revered cookery writer in his time, but he had no truck with the idea that good food must take ages to prepare. He’s funny too, and his recipe for Tomato Sauce tastes better than it really ought to.

Author: Susan Low

Related Posts

French Food Quiz

Michelin-starred chef Daniel Galmiche lends his expertise to our French culinary quiz.

Behind the Cookbook

Anne Willan on La Varenne Pratique.

Sign up for ckbk's weekly email newsletter

Advertisement